All or None

In 1946, Penn State was scheduled to play the University of Miami, which like most Southern teams of the time still refused to play integrated Northern teams unless they sat their Black players. At the time Penn State had two, and of them only Wally Triplett was a regular. By a team vote, PSU canceled the 1946 Miami game, an act that Triplett credits for the origins of its great 1947 campaign, when Penn State swept its regular season opponents and earned an invite to the Cotton Bowl.

The Cotton was one of four bowl games in existence, and one of three, the Rose excepted, with standing rules against Black players participating. Responding to rumors that administrators were talking to SMU about sitting Triplett, PSU captain Steve Suhey told the press “We play all or none, there will be no meetings.” Triplett played, and scored the game-tying touchdown. Though the school’s claim that this event and the “We Are…” cheer are connected is completely apocryphal, the moment is a special point of pride for the Nittany Lions.

Michigan could have had that moment a dozen years earlier, when Georgia Tech came to Ann Arbor in 1934, and over vocal opposition from campus protestors and the greater Michigan community, Fielding Yost agreed to sit star end Willis Ward. The details of this event have been covered many times, first as dug up by Dr. John Behee in his first book Hail to the Victors! Black Athletes at the University of Michigan (1974), then in the Black and Blue documentary based on his findings, and most recently and thoroughly by the President’s Advisory Committee Report on the Fielding H. Yost Name on the Yost Ice Arena Historical Analysis.

Yesterday this committee tasked with looking at whether Michigan should rename its buildings issued its unanimous recommendation to President Schlissel that Fielding Yost’s name should be removed from Yost Ice Arena. The report is 36 pages, and informs the committee’s six-page unanimous recommendation.

As someone who talks Yost history often, most recently in an interview on the history of the Big House that aired on student television, I hope to provide some context on the committee’s findings. I will refrain from adding my opinion on the building’s name until the end because next to the facts and the opinions of those more directly affected I don’t believe my feelings, colored as they are by my history of covering Yost, should carry much weight.

Committee, Report and Conclusions

The committee begins their recommendation letter with an unattributed message from a Michigan alum asking that the name be reconsidered because “In naming the Field House after Yost, the University chose to place one man's contributions to football and to athletics above the profoundly deep and negative impact he had on people of color,” and continued to do so over several opportunities to rename it.

The committee responds to this in the summary of its conclusion:

While we acknowledge that Yost had both successes and failures in his career, our historical analysis suggests to us that the benching of Ward was not an aberration but rather epitomized a long series of actions that worked against the integration of sports on campus.

The committee also lays out what it believes should be the standard for “honorific” naming of buildings, which is:

The names on our buildings constitute a “moral map” of our institution and should enshrine the values that we uphold.

By this standard they make a convincing case that Yost’s actions in the Willis Ward affair did not represent core values of the University of Michigan as they were formally stated in Yost’s time, or as they are instituted in practice today.

The committee was created in 2017 as the active arm of the university’s new review process for renaming buildings, and President Schlissel followed its first two recommendations, removing the names of noted eugenicist CC Little and crank scientist Alexander Winchell. In the future the same committee will likely be tasked with a recommendation on the honorific naming of Schembechler Hall, and the financial naming gift of the Weiser Center for Emerging Democracies.

[Hit THE JUMP]

Findings of Racism

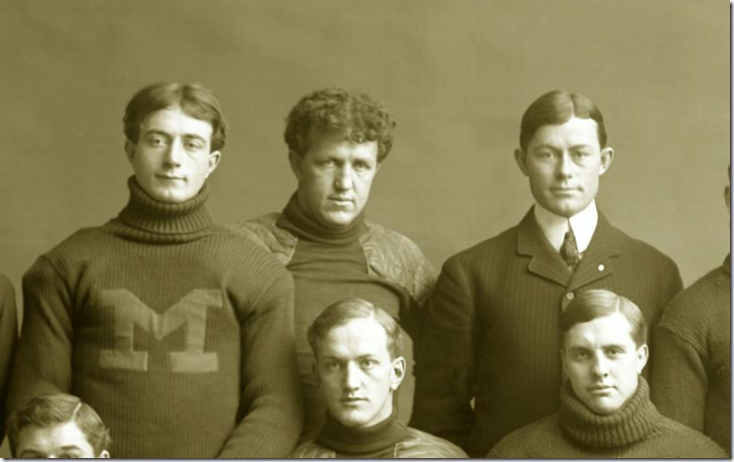

Dan McGugin (far left) was a star on the first Point-a-Minute team. He would become Yost’s brother-in-law, and but for a WWI interruption, coached Vanderbilt from 1904 to his death in 1936, upholding the Vandy administration’s color line on all of his teams. George “Dad” Gregory (center) came with Yost from Stanford, and was thereafter the subject of Stanford president David Starr Jordan’s persistent and unsubstantiated claims of cheating. Stanford recently removed Jordan’s name from a building; Vanderbilt’s athletics building today is still called the McGugin Center. [team photo, courtesy UM Bentley Library]

The report describes Yost’s background as the son of a Confederate soldier (from a Union state so this was by choice), who spent time socially in the Sigma Chi Fraternity and Nashville upper society, which he married into. They paint a picture of a patronizing “moderate” form of racism, one which was tolerant of segregation but not the violence that enforced it, as was the norm in these circles. There are few signs that Yost ever deviated from this norm.

Most of the report focuses on the Willis Ward scandal in 1934, when Yost not only chose to accede to Georgia Tech’s racist request to sit his star Black end, but hired Pinkertons to report on the leaders of the campus movement to play Ward or cancel the game. Prepare to cringe at Yost’s Michigamua nickname as well as the all-too-familiar behavior of the campus anti-anti-racism movement:

This disruptive group included athletes and fraternity members, but its core were the members of Michigamua, the supposedly secret senior honors society. The group had a very close relationship with both Kipke and Yost, the latter of whom was known as the “Big Scalper.” It is almost certain that the group had been asked to disrupt the meeting, by either Yost, Kipke, or both; in a 1942 alumni questionnaire a former Michigamua member recalling the event asked that the interviewer include “a good plug for Kipke who was behind us.”

If you consider those protesting the sitting of Ward were squarely on the side of history, Yost’s characterization of the student protestors leaves little doubt which side he was on:

In a letter to his brother-in-law Dan McGugin a few days after the game, Yost gave a literary sigh of relief that there had been no disruptions by “the colored organization and local radical students,” commenting that “the colored race must be in a bad situation judging from the number of national organizations that are organized to insure [sic.] racial equality or no racial discrimination.”

In December, Yost wrote to Georgia Tech’s coach, to “express to you personally my great appreciation of your assistance in handling what turned out to be a very difficult problem. I never dreamed there would be so much agitation about the matter.” In neither letter did Yost reveal any interest in second-guessing events, his role in them, or their impact on Ward.

And Willis Ward’s own words on the effect of the incident on himself and his team are excruciating to read:

That impact was devastating. As Ward himself later put it: “It was wrong and it will always be wrong. And it killed my desire to excel.” The same malaise struck the entire football team. Already a weak team that had lost the two games before the one against Georgia Tech, they lost every other game of the season—with Ward scoring Michigan’s only points, a touchdown and two field goals, in the remaining five games.

Ward also lost his competitive drive for competing in track, stating later that he did so out of a belief based on his brush with Jim Crow in Ann Arbor that if Hitler asked the U.S. to leave Black athletes off the 1936 Olympic team, they would. As he summarized in a 1983 interview, the Georgia Tech game “killed my desire. I said, well, I will go through the motions and play this season and get my degree and go about my business and try to get a law degree and practice law.”

There is no doubt that Yost’s actions regarding the sitting of Willis Ward were racist.

The report notes concerns held by Ward about attending the university because of stories of racial prejudice in Ann Arbor. The report demonstrates Ward’s (and really his father’s) apprehensions were well-founded, with ample evidence of racism in the actions of the university administrators Yost worked with and around, notably regarding on-campus housing, which was generating controversy for the school at the time of the Ward incident. They also found other Michigan sports when Yost was the football coach but not yet an administrator (and thus out of town 9 months out of the year) had similar or worse records of integration.

I can add from my research on Ann Arbor that several off-campus establishments of this era were particularly notorious for “unofficial” racial segregation. While anti-racism found its voice in a flourishing new campus left in the 1920s and 1930s, a large proportion of mainstream culture at the University of Michigan in that time did not differ significantly from the portrayal of Yost in this report.

Evidence that Yost’s actions “epitomized a long series of actions that worked against the integration of sports” in the report is sometimes contradictory.

Certainly the lack of any Black varsity football players from 1901-1931 (though teams were much smaller in that time) is the strongest evidence that Yost’s arrival “disrupted Michigan’s participation in the slow process by which racial integration in football was occurring.” George Jewett was the first Black player at Michigan or any other Big Ten team, but when he transferred to Northwestern in 1893 he became the last at Michigan until actions by well-meaning Michigan alumni convinced Ward to join the team.

The report notes that the lack of Black athletes on the football squad was remarked by the African American press, and that Yost’s color line, even if it wasn’t explicit, was known to the African American community, as this example from 1932 (regarding Willis Ward playing for Harry Kipke) suggests:

In 1932, when Ward made Varsity it was reported by Black newspapers “that it was the contention of many that former Coach Yost was prejudiced against the colored player” and that when he first arrived in Ann Arbor he was “alleged to have decreed…that no colored student would ever earn a varsity letter” in football.”

The report did not include one more quote I have to this effect, from former Michigan tennis player Dan Kean, a senior in 1934, who later said “If you want to know what it is was like then I’d have to say black students were AT the University but not OF it.” While evidence for a policy of exclusion was (by design) scant, Yost and Michigan had a reputation; the result of this reputation was Black athletes did not think to come to Michigan.

Yost certainly didn’t step in when basketball coach Frank Cappon refused to let Black athlete Franklin Lett try out for the basketball team. The report includes more incidents when Yost missed an opportunity to stand for justice. There’s a reference to “a simple, Anglo-Saxon desire for clean, energetic sport” by Yost’s ghostwriter in 1905 that he allowed to stand.

The report also notes Yost spoke at the Third Race Betterment Conference, organized by then-Michigan president CC Little. Yost’s words, other than a reference to the conference’s own racist title, were mostly innocuous and in line with his “athletics for all” mantra. But Yost was hardly unused to standing up to Michigan’s presidents when it came to support for athletics, and could have done so here.

The report quotes Yost’s second (there were three) successor as football coach, Tad Wieman, with this particularly noxious example of “Nobody Short of Jackie Robinson” syndrome:

There were certain complications that would be difficult for all with a colored man on the squad; that because of this I did not think it advisable for a colored man to be on the squad unless he was good enough to play a good part of the time. In other words, unless he were a regular or near regular, the handicaps to the squad would be greater than the advantages to say nothing of the difficulties that would encounter the individual himself. I assured him, however, that any man who could demonstrate that he was the best man for any position would have the right to play in that position.

There are also instances in the report when Yost’s actions showed, at least outwardly, that he was at least changing with the times. Regarding the most evident one—that Yost had no Black varsity players on his football teams for 30 years—this exchange with the African American press was interesting:

However, the lack of African Americans who played on Michigan’s Varsity football team began to be noticed in the African American press. In 1922 (the year before the Field House was named for Yost) two articles appeared discussing race in the athletic department. The first appeared in February in the Chicago Defender, which had national syndication, regarding rumors about a “color line” in sports at Michigan. The article quoted a letter from Yost to Oscar Baker, the Black alumnus and lawyer in Bay City who would later help African American students with their housing issues, stating “very positively” that “a Colored student athlete stands on the same footing as regards athletics as anyone else in the university.” Yost claimed that he “would not consider a coach worthy of the name who did not feel that the best men qualified to make up the various teams should have a place.” Both Baker and the article accepted Yost’s statements, commenting, “if the student body has Southern traditions, the same does not affect the athletic department.” A month later, the Cleveland Gazette published an article about Black Ohioan DeHart Hubbard who had just enrolled at Michigan. In it, Yost approvingly described Hubbard “as a boy they were pleased to have at Michigan and stated he intended to see that he got a square deal.”

The report found Yost supported a “Law and Order League” in Nashville whose purpose was to prevent lynching, and they found other Black athletes who participated in football despite not making varsity, undermining the link between Yost’s views and Tad Wieman’s remarks. They found Yost, upon becoming athletic director, cooperated in the recruitment of Black track star William DeHart Hubbard, citing Behee’s characterization of this as motivated by competitiveness. And they found public support (one time) for an organization that helped local Black families, and an antipathy for anti-Semitism and support for Jewish athletes that was somewhat remarkable for his time and place.

Errors, Omissions, and Criticism of the Report

For the most part, the 36-page report is a fair and comprehensive account of the consensus historical knowledge of Yost’s record on race. But there are a few significant problems with it, and I also have some questions about their conclusions.

The report makes numerous references to works by Dr. Tyran Steward, a former UM lecturer (and Ohio State Ph.D.) working on a book about Willis Ward, but does not mention another famous Yost incident from Steward’s research that conflicts with portrayal of Yost, this from 1932:

Although Big Blue relied on the Palmer House Hotel for lodging through the years, the hotel’s management was unreceptive to the requests made by Kipke for Ward to stay there. When they declined to alter their policy, “Yost flip-flopped from being a segregationist.” Ward remembered Yost saying, “Well, we have been staying at this hotel since 1900. We will pull every team that we have and not stay. . . . And I am going to see if I can’t get other Big Ten schools to also not stay at your hotel.” Officials at the Palmer House Hotel relented.

Most of our modern discussion of the Willis Ward incident, in fact, draws heavily on the research and conclusions of Behee in his first book. Behee is a friend, his recent book Coach Yost: Michigan’s Tradition Maker comes recommended by myself and Craig Ross on this site, and Behee has contributed an article on Yost for our Hail to the Victors 2021 magazine this summer. He was not contacted by the commission. Other experienced historians like Dr. Steward, John U. Bacon, and John Kryk who have written books about Yost, can give you a stronger answer than I can, and probably could have done better than the report. So could Greg Kinney and Brian Williams at the Bentley Library. Greg Dooley, the program’s historian in chief, was not even referenced in the report.

The report explicitly drew from familiar works of these historians, though to my knowledge none of them were informed their writings were being used for this purpose, nor that the committee was considering removing Yost’s name from the hockey arena. I believe the committee erred in not seeking feedback from these experts before publishing their recommendation, as this can be interpreted as disinterest in interpretations that do not fit the committee’s conclusions.

I also found one important note was misrepresented in a way that may have played a role in the conclusion. On Page 26 the authors write:

There was some precedent for that hope. McGugin had told Yost how when Ohio State played against the segregated Naval Academy, a Black player, William Bell, was not permitted to play against the Midshipmen in Annapolis, but was allowed to play the following year in Columbus. The Vanderbilt coach had also claimed that he had been willing “not to make any particular point [about playing against Bell] as we were going to their field” in 1931, but he had been overruled by Vanderbilt’s Board of Trustees.

While Ohio State did allow “Big Bill” Bell to play in the return game against Navy in 1931, they only did so because the Naval Academy, under its new head coach Edgar Miller, changed its policy in the interim, a fact that McGugin explained in his letter to Yost (see Benching Jim Crow: The Rise and Fall of the Color Line in Southern College Sports, 1890-1980, by Charles H. Martin). Ohio State benched Bell in the 1931 Vanderbilt game prior to the second Navy title, and in all three of those games deferred to the visitors’ requests. By 1934, Ohio State had hired a new coach who reinstated the color barrier for the rest of the decade, refusing to even let Jesse Owens try out of for the football team (their administration wouldn’t let Owens live on campus either). Yost’s diffident approach in the leadup to the Georgia Tech game was probably seen by him as a softening of OSU’s example.

This is part of a greater failure in the report to contextualize Michigan’s racist performance under Yost against norms for similar schools of the day. I believe this failure is mostly due to a lack of information, not willful ignorance. The report makes reference to only three other studies, two by Ivy League university presses and one by Stanford. The latter (the link in Michigan’s report is broken—the report can be found here), ironically concerns Stanford’s founding president, David Starr Jordan, who in addition to being a leading eugenicist was Yost’s greatest contemporary critic. Michigan knows much more about its racist past in the early 20th Century because we have authors who’ve studied it; few other schools have partisans so willing to look under the hood.

One line of evidence they did not follow but could have used to enlighten Yost’s racial attitudes was his relationship with other important figures at the university in his time. Yost was close with his immediate predecessor Philip Bartelme, his former player and team manager, and athletic director from 1908-1921. Yost was also often in contact with 1910-1913 baseball coach Branch Rickey; Yost trusted him enough to hire Del Pratt and then Ray Fisher on Rickey’s recommendations. Bartelme left Michigan to join his good friend Rickey in Major League Baseball, where Bartelme scouted and Rickey signed Jackie Robinson. It’s a fact that Michigan had no Black baseball players from 1883 to 1923, at which point Yost supported Rudy Ash’s joining the team, under Fisher. Yost’s close association with two men involved in the most famous desegregation moment in sports history is worth at least exploring, especially since their own records at Michigan are hardly better than Yost’s.

There’s little doubt Yost had the power and opportunity in 1934 to support Willis Ward had he chosen, or that some actions by Kipke and associates could be interpreted as carrying out Yost’s will. The report claims Yost was “disappointingly enabled by” 1929-1951 president Alexander Ruthven and members of the Board of Control, though concludes that “our research convinces us that he must bear the responsibility for the actions described in this report.” It is interesting that contemporaries who sought to change Yost’s “cowardly plan” addressed themselves to Ruthven. This could have been because they saw Ruthven as more receptive to their pleas, but could also indicate a balance of power. I also find it interesting that Yost’s most progressive acts (and indeed his hiring as athletic director) took place during the 1920-1925 tenure of President Marion Burton, who was by accounts Yost’s only true ally and friend among the presidents he served under. A more thorough understanding of Yost and other power figures’ relationships and spheres of influence might allay doubts as to which figure bears the brunt of responsibility.

I did not think the evidence in the report supported one of the conclusions, that Yost “endorsed the view that football was an Anglo Saxon sport at a time when that identification carried powerful racial messages.” It’s certainly easy to point at the 1905 book and say “It’s got his name on it.” However the footnote in the report is correct in that consensus historical opinion holds Yost was unlikely to have contributed that line:

Yost was listed as the author on the book’s cover, but the text likely came from Charles Van Keuren, a Michigan alumnus who sought to capitalize on Yost’s fame to boost sales. Per their arrangement, Yost would supply the copy, play diagrams, and team photographs, while Van Keuren supplied the text. Thus, who penned those words is unknown, but Yost clearly did not strongly object to them.

The report also misses some important context by ending its story with Yost, which was absolutely not the end of racism in Michigan’s football program or athletic administration. Fourteen years after the Willis Ward affair, the fall after the Cotton Bowl and SMU quietly backed down after a Penn State player said “all or none,” Gene Derricotte was the only non-white player on Bennie Oosterbaan's 1948 "Mad Magicians" team, which repeated as national champions. A decade later the roster had expanded considerably, but Michigan still only had three Black players on it. Behee’s book has direct evidence that after “integration” Michigan participated in an unofficial quota system that kept Black participation to just one player per class until 1968, an effect you can literally see in the 1969 team photo:

I don’t think more examples of racism in Michigan Athletics in any way exonerates Fielding Yost for his actions. To the contrary I think these examples underline the severity of it, and how deeply rooted, though quiet, these practices were, and therefore how righteous and necessary the campus activism of Black students and their allies was to effect change.

My Interpretation

Michigan named the rink for Red in 2017. [Bill Rapai]

I speak here for myself, not for MGoBlog or anyone else who works here. I’ve studied a lot of Michigan history from before, during, and long after Yost, and from that I can say with some authority that racism at Michigan neither began nor ended nor changed much on account of Yost.

The Crisler era that followed was marred by unofficial quotas to keep Black players to a minimum. Schembechler made it clear to his players they were to stay away from the successor movements of the social justice activists of Yost’s time. When I was at Michigan in the early 2000s and the school’s admissions policies were national legal news, the College Republicans were given permission to set up in Angell Hall selling “Affirmative Action Bagels” that were $1.00 for white customers and 10 cents for Black students. I doubt any Black student in the history of the school has ever made it through their scholastic career without at least some racist incident on campus. Racism at Michigan isn’t some nebulous problem of the past. It’s our reality today.

How does it happen? Read the report. It’s a culture, a cancer, and nothing would have changed if there hadn’t been people who cared more about justice than whether “polite” society gets smacked in the face.

As for Yost’s culpability, of course he knew he was wrong; why else would this man who loved the limelight suddenly shirk it? Why else would the most competitive man of his era sit one of his best players, or a coach whose entire style was about building up confidence undermine his team? That this was not unusual for a man of his times who mostly changed with his times does not dismiss his failure. He no doubt failed to meet the moment when Michigan played Georgia Tech in 1934, and his subsequent actions to defend his decision rightfully earn him censure by future generations. This was the definition of an “I don’t see what the big deal is”-style racism that allowed that culture to flourish then and survive today. Placing the blame for the effects of one’s moral cowardice on “radicals” and “agitators” had miserable precedents then and more today.

Yost’s upholding of the “gentleman’s agreement” is evidenced enough in the makeup of his teams. If we all take away nothing else from this report, I want us all to understand this is how racism works. It’s not the things that are said aloud, because the whole point is not to have to say anything. Black athletes knew not to play for Michigan under Fielding Yost. When one man finally did, his worst suspicions were confirmed. Yost made racist decisions, and I’ve had no problem saying so when I talk about his contributions to Michigan athletics. I do not find him in any way remarkable in this regard from other athletic directors of his era, and I have no problem with calling out the lot of them if it helps us move past the decision cycle.

I find attempts to place one man on this curve, with “Okay, you can keep your name on your building” at some undefined point along it, to be a shallow exercise for people who want easy labels. The whole society was racist, but inside of that you had some people trying to change things for the betterment of us all. It’s better that we named the renovated room in the student Union after Willis Ward, and that Michigan and Northwestern are choosing to honor George Jewett. Whatever you do with Yost Ice Arena, find something to honor Joseph Feldman, William Fisch, and Danny Cohen, the names of student ringleaders Yost’s Pinkertons gave to President Ruthven, and who were quietly dismissed in July 1935. Without those three the next administrator faced with this question would not have feared a backlash, as Yost didn’t after the example of Ohio State. Whatever they do with Crisler for the quota system, I think we need to honor the few guys who did come: Guy Curtis, David Raimey, Bennie McRae, Jim Pace, Bob Marion, Lowell Perry, Gene Derricotte, and more who had to be greater than great, and carry the reputation of millions with their own.

I believe Willis Ward that Yost’s decision ruined him and the team, as I believe Triplett that his teammates’ support motivated their great 1947 run. I believe that this extends to the Michigan community and greater society, which becomes energized when we stick up for each other, and demoralized when we don’t.

I personally don’t have much care for what a building is named. I have great memories in Yost Ice Arena, and they won’t be affected if it’s renamed Berenson Ice Arena, because most of those experiences were thanks to Red’s teams. If years from now history shows Berenson failed in his moment, they can change it to Hughes Arena to honor the 30 first rounders that family sent here.

I find most conversation around honorifics either obvious or boring, and this one falls in the latter camp. C.C. Little got a building because they noticed all but two presidents—Little and Ruthven—weren’t going to have buildings so they found a pair. Winchell got a house because they needed nine former professors with long tenures. You spent more time reading this than the people who named those spent on their subjects. It’s an easy call.

Yost Ice Arena is not. It’s a balance. The Field House was named after him because he invented the concept, and the name was bestowed after another contentious fight between the faculty who found Yost’s zeal for athletic competition distasteful, and the regents and alumni who were all about the football. His association with hockey is equally earned; Yost raised the hockey program to varsity status in late 1922, and in 1928 he purchased the Weinberg Coliseum they’d been renting, renovated it, and filled it with artificial ice, just before the Depression hit and ended all the building projects. His impact on campus was such that I could make a similar case for almost any sport, and his impact on women's athletics at Michigan is second only to the passage of Title IX.

His impact on Black athletes and would-be athletes who never got a chance to play at Michigan may not have differed from an average man of his time, but it was manifest. When nearing the end of his career he had a chance to demonstrate his growth, Yost chose to duck. That is now as much a part of his legacy as the buildings.

I believe the racial issues at Michigan in Yost’s time were systemic, and while it’s fair to hold one man accountable for his role in that system, wiping his name from the building is a performative gesture, not a remedy. More than a name, I think there should be a bronze placard outside the arena, telling the Willis Ward story where people waiting for their friends will read it because it’s too cold to hold a phone in your face.

I’m less thrilled about the standard that “The names on our buildings constitute a ‘moral map’ of our institution.” I think this runs the risk of making honorees two-dimensional, and will lead to more icky donor names that are harder to correct. History is not a moral map. It shows us where we’ve been, what choices led to darker paths, what perils might lie along the way, and how we’ve corrected mistakes.

More than anything I think that the 36-page report produced by the advisory committee is something every Michigan fan should read, especially if you choose to comment on this after. More important by far than the measure of one long-dead man is that we gain a better awareness of how regular living men and women contribute to racism at the University of Michigan, and how being a part of this society has soaked the stench of it into all of us. If you’re pointing to one guy and saying “He’s a racist (and because I’m pointing I’m not),” you’re missing the point.

I think the story of Willis Ward, and the context it happened in, are relevant today. I think his heroic choice to rebreak Michigan’s color barrier should be celebrated, that the efforts of his recruiters should be recognized, that people should know if not for Harry Kipke those recruiters probably wouldn’t have even tried. I think we should honor the heroic voices of activists of the past, and that the righteousness of the causes they agitated for are instructive in how we regulate our annoyance at their successors’ insistence we face our facts. I think knowing the particular way a man like Fielding Yost failed will help us find our voice when it’s our moment.

Ugh...I did. Thanks for correcting me....I’m betting Willis Reed has a few stories as well though right?

Willis Reed had some pain, limping onto the court and all that.

This is a great post.

As an alumni of color, a lot of these points resonate, and I'm still sort of torn on what to do. I plan on reading the full report later to make sure I develop a properly informed opinion. But this was incredibly helpful.

One of the most eloquently written, detailed, and nuanced articles I have read on this blog. Truly remarkable work. Many thanks.

I'm agnostic on the question of Yost's name, but I suspect in this current political environment that removing it is inevitable.

I think the larger question at hand is this: Is there anyone in human history who deserves to have any facility, road, bridge, school or landmark named for them?

No matter which person from history you examine, each of them have major holes in their history which would under today's standards make them ineligible for such honors.

The larger question is this: should we honor anyone ever with naming objects, awards, statues etc after them?

Today's environment would say the answer to that is no. It's not worth it, and it's only a matter of time before those yet to be born use yet to be defined standards to render retroactive judgement upon us all.

"When I was at Michigan in the early 2000s and the school’s admissions policies were national legal news, the College Republicans were given permission to set up in Angell Hall selling “Affirmative Action Bagels” that were $1.00 for white customers and 10 cents for Black students. I doubt any Black student in the history of the school has ever made it through their scholastic career without at least some racist incident on campus."

Given the close proximity of these two sentences are we meant to conclude that any person who opposes/opposed what was called "affirmative action" is/was a stone racist?

I don't think what Seth said there means that opposing affirmative action is/was racist. But it is a pretty clear example of sophomoric insensitivity that had to be pretty painful to African-American students.

If you have ever set foot in Ann Arbor, you would know the answer to that question.

You're falling into the trap that Seth warns against in this very piece - people are not two dimensional. Were the actions of the people doing the bagel sale racist? I think it's hard to argue that the action wasn't racist. Are those people racist? Depends on the rest of attitudes and actions, which we are not privy to.

So your view is the bagel sale was racist in that it highlighted racist behavior from the university?

I'm curious - what would a non racist protest of the racist admissions policy have looked like?

lol. I don't think I'm going to entertain your bad faith argument.

I accept your surrender.

Congrats, you won the imaginary, poorly framed “contest”

Not my job but whatever yall been doing it's working.

Same question to you.

What does a non racist protest against the University’s racial policies look like?

Hmm, that's tough. I'll try.

You'd have to have a week long bagel sale. On Monday, you sell bagels to white students for $1.00. Black students are kidnapped and forced to make bagels. Tuesday and Wednesday you sell white students bagels for $1.00 while killing, raping and beating black students as they make bagels. Thursday you sell bagels to white students for $1. You tell black students they don't have to make bagels anymore and can buy a bagel for a dollar but instead you intimidate, beat, kill and otherwise prevent them from buying a bagel. Friday you sell bagels to 90% of the white students for $1. You "allow" ten percent of the black students to buy a bagel for $1 and have a group of white students stand around bitching about it.

I am usually in favor of removing names and statues of individuals because I think there's a tacit approval of their transgressions when those things are up. I also recognize that it's mostly a symbolic gesture, but that's ok because symbolism can be very important in society.

But what I am most interested in is what Michigan does from here. Removing the name doesn't help the people that were wronged by Yost. Probably nothing will reverse the wrongs. But Michigan could fund an affordable youth hockey league in the area, focused on underprivileged youth. Fund youth programs in Willis Ward's hometown in Alabama. Stuff of that nature may not undo Yost's wrongs but it goes toward building a better future for everyone.

Thanks, Seth, for an excellent article. Thanks for the clarity and the context. I think for most of us who went to UM, the name on the field house speaks more to our memories than to the man. I'm old enough that it was $1 beers for home games at Yost when I was a student -- they were packed and frenzied as a result. At the same time, the case for removing his name is not slight.

It also shows, I think, the difference when it comes to Bo and the deplorable Dr. Anderson scandal. Unlike Yost, Bo is not accused of taking actions that directly harmed people but of not being on the ball about what he was hearing from emotionally wounded players. Doesn't exonerate Bo, but it does put his situation in context.

Chuck Christian is dying because the trauma of his experience as a Michigan football player with Dr. Anderson led him to avoid doctors his whole life until it was too late to catch his illness in time to cure it. Bo's inaction is directly responsible for impacting his life by cutting it short. Inaction was his decision.

Bo is not accused of taking actions that directly harmed people [...] Doesn't exonerate Bo, but it does put his situation in context.

Only if you play word games in your summaries of the events.

Bo absolutely took actions. Bo's action was to look the other way.

Well measured approach here, thanks. Well done.

I'm also generally indifferent on the name on the building. As other have mentioned here and in past threads - applying present day norms to the past is somewhat unfair. That said, I also simultaneously understand the alignment to present day values take.

I think regardless of whether or not the name is changed, put up a glass case in the arena highlighting Willis Ward's story and bio. Removing the name does nothing to further education.

I don't understand this argument that demoting Yost to human status is based on "applying present day norms to the past." Do you really think that Gerald Ford (and all of the others who objected to Yost's decision at the time) travelled back in time from the present to apply the standards they applied?

Keeping the name does no more to further education than removing the name does.

Great read. As a non alum (my fandom is a long story) and a black man I found this very interesting. These are the articles that keep me coming back even when the football team and message boards are in shambles. Thanks Seth.

Well done, Seth. Well done.

Thank you for this Seth

Seth, I think this was a well written reasoned take. I don't agree with your assessment that changing a name is strictly performative. While it is certainly not even close to enough in changing the ongoing reality, it is also a necessary step. Naming a building after someone is choosing to endorse them overall. A key context of racism is that it is systematic and not just a series of individuals doing individual racist things. But part of that system is overlooking the individual racism. Taking that down as something to be celebrated isn't erasing history and it does send a powerful message that means something to people. The idea that saying we no longer wish to honor this man isn't an erasure of history, its not setting history as a moral map, its saying that they do not wish to honor the man.

I also don't really get the obsession with plaques. People don't read plaques, plaques don't get talked about during games on tv. They are a solution to nothing and add essentially no nuance. Its a throw away gesture. As long as Yost's name (or Crisler's) is on the arena it is a celebration of that person by the university. That is the problem with naming something after someone. There is no nuance to sculpture. You can say the man was flawed, but what you are ultimately conveying is that overall the man (or person) is worth celebrating, is an exemplar that we want to hold up. The lack of nuance is part of why I think naming anything after anyone is stupid but its too late to add nuance to it. The name should come down because the options are either its that or you choose to still celebrate Yost. I don't believe he is a man worth celebrating as an exemplar. He is not seemingly an evil man, he was not especially out of line with his times, but he was also not an exceedingly great man, who was out of line with his times in a positive way and thus is deserving of being celebrated. He was a successful AD, the existence of Michigan football as a national brand is thanks to him, none of that justifies being celebrated as a person.

There is certainly some history of institutional racism at M, but this isn't one of them: "When I was at Michigan in the early 2000s and the school’s admissions policies were national legal news, the College Republicans were given permission to set up in Angell Hall selling “Affirmative Action Bagels” that were $1.00 for white customers and 10 cents for Black students."

As a public institution, the university has to have extremely broad free speech rules. Shutting that protest down would have caused other protests to be shut down, as well. At a small-L liberal institution, they choose to have more speech than less. This broad latitude at the university goes back to abolitionist marches, etc.

My take on that situation is that it wasn't necessarily a fault of the institution, for reasons you stated quite well, but rather, as an example of ongoing racial animus in the near past/present day.

The "institution" in this case isn't the university, it's the society that enabled those College Republicans to think that was an acceptable activity.

I agree. Removing the name is more performative and is all about the university's image. Whether or not the name is removed doesn't move the needle one way or the other because Yost is dead and the past is the past. A dollar late and day short in that respect.

I think I realized that it's not the cancel culture or the attempts at holding historical figures accountable to today's standards that bothers me. It's the energy, time, resources used toward pointing the finger and trying to paper over historical injustice with well meaning symbolic gestures. I wish the same energy and passion was displayed toward efforts of honoring the folks who haven't been honored bc they weren't allowed to be. How about a huge fucking statue of Willis Ward in front of Yost Arena. Focus more on honoring the people who did demonstrate the values of the university even more prominently for all to see so history can been seen in it's proper context and we can see how far we've come and where we can aspire to be.

I think this was a great post. The arguments about Yost's legacy can be conducted with relative calm and a great deal of perspective given how long he's been gone. No one reading this blog was alive when he was an AD at Michigan or has met him. This discussion will be a good way for people to reflect on where they stand with the idea of honoring past heroes who may have been flawed. But the REAL debate is coming with Bo's legacy. There are still a vast number of Michigan fans who have a strong connection to him and his achievements here, since it was a part of their lives for a long time. That will make for a much more emotional debate, that I hope doesn't somehow form a schism in the fanbase.

Sadly, I suspect your prediction will turn out to be completely wrong.

There won't be a debate.

Debates involve an exchange of views.

What is coming will be a mandate and orders to fall in line.

Dissent is not going to be tolerated.

Could you be any more of a drama queen?

Interesting phraseology, “drama Queen.”

You do realize the misogyny embedded in that phrase will lead to you being unfit for future societies, right?

For one - if they see my post they’ll also have seen your hand-wringing, pearl clutching hysterics and agree that you are, in fact, a drama queen. And even if not - I’ll be dead, and since I’ll be in the ground, IT WON’T FUCKING MATTER, not one bit.

There's no misogyny in the use of the phrase, according to all the dictionaries, the Washington Post. Psychology Today (both of which use it), etc.

Stop being such a drama queen about the phrase.

Thanks for laying it out so well. Two things to add.

I think Willis Ward, who was there at the time, is exactly right when he says, "“It was wrong and it will always be wrong." Ward was a person of his times. He was right, and Yost was wrong. I think a useful way to think about naming is to ask, "What would Willis Ward want, if his great-grandchild were to attend Michigan?" We can't know for sure. It's a place to start.

I went to Michigan and I'm proud I went to Michigan, partly because I believe any great educational institution should aspire to be better than its times, not in line with them. The best you can say about Yost is that he (like all of us, most of the time) failed to be better.

So glad people that are perfect are making things perfect.

Indeed. Although you might have said "perfect people making the past perfect while ignoring the present."

Stop being such a drama queen. The only person here that seems to be ignoring the present is you. For the rest of us, this isn't about the past, it's about what to do in the present, to serve the needs of the present and future.

Great work, Seth.

The Advisory Committee got it wrong and Yost's name should stay on the Ice Arena, in honor of his work in building the field house and elevating the hockey team, in addition to his general contributions to Michigan Athletics over 40 years. Having a building named after him is symbolic only of the good things he did for the program, and not an endorsement of the areas where he fell short of standards.

People are using lots of weasel words to avoid sounding improperly dismissive of racism. Half the commentors start their post with some version of "I'm on the fence," "I'm agnostic" or "I don't care." Maybe that's true, but to me it feels like a cop-out of having to make a hard moral decision. It's easy for randos on the internet to try to appease everyone by attempting to take a middle path, but I have tons more respect for the Advisory Committee (in favor of removing the name) and Seth (in favor of keeping it, apparently) who took a firm stand on a difficult issue.

Even so, both sides feel the need to put thousands of words ahead of the final decision, rehashing history that is already pretty-well known within the Michigan athletics circle. I find it remarkable that Seth feels the need to pay the proper respects to the racist history, as if he goes too lightly on the details in the "Findings of Racism" section then someone will accuse him of being racist by not taking it seriously enough.

I'll give Seth a partial break since he knows his audience on this blog is likely to go beyond fans familiar with Willis Ward and other stories of Yost's racism; and because I know that writing with many, many words is just part of his style (that's not a criticism, by the way. This post is getting long too). Still, there's a pattern in social media where writers have to establish their not-racist bona fides to pre-empt annoying criticism from the crowd. Seth put it better than I could: "He’s a racist (and because I’m pointing I’m not).” I see too many people do that, and move to the extremes to shout down reasonable, nuanced takes such as the one Seth put up here.

If Brian's only response is a tweet that says "leave Yost Ice Arena alone" I'll be so happy I'll probably buy a t-shirt from the MGoStore or something.

Ok how about this:

The advisory committee got it right and Yost's name should be removed. He did not do what was morally correct, and failed to show enough growth to be considered a moral icon. He disenfranchised black athletes and should not be celebrated by having a building named after him.

FDR did much worse and so-called Progressives openly invoke his memory with the “Green New Deal”.

There are many places named after “problematic” people and groups that get ignored because of the singular focus on anti-Black racism.

This is (I hope ironically rather than deliberately) an example of the "we can't fix everything, therefore do nothing" approach to solving systemic issues.

I much prefer the "ya gotta start somewhere" approach. And renaming buildings and removing statues may not be everything, but it is not nothing, and in some ways it's the least we can do.

And before it comes up, I'm not saying we should stop there, nor do I have any patience with the "ugh we already tore down the statue, isn't that enough?!" argument. Remove his name, and keep looking for other ways to chip away at systemic issues.

Also, I promise that when you lay out your case for renaming the FDR, I'll listen and not say that you're focusing on trivial issues when <gestures at pervasive systemic issues> exists.

FDRs record is far worse than Yosts and is closer to George Wallace than Lincoln.

FDR was elected under Jim Crow and did nothing to end it.

FDR presided over a segregated military and resisted efforts to integrate it.

FDRs vaunted Social Security program largely excluded blacks.

How can you not know any of this?

FDR signed the Fair Employment Practice Committee Executive Order, which forbad discrimination in hiring or pay in the Federal Government and in all companies that wanted Federal contracts. He did not at all resist integration of the military, and agreed that it should happen after the war (which it did).

It is true that the Social Security Program included only industrial workers in large corporations, not professionals, farmers, self-employed, store owners, etc. This disproportionately impacted blacks, for sure, because domestic workers and farm laborers were disproportionately black. But the reason was because there was no way to collect SS taxes at the time from anyone not employed by a big industrial firm.

How can you not know any of this?

But none of your accusations about FDR actually amount to any acts of animus. That definitely cannot be said of Yost, and that's why we need to stop pretending he was some paragon of virtue worthy of immortalization through a building name. We can be better than that.

I was at my kid's baseball game last night so wasn't able to re-defend my position. You did so extremely well. Thank you.

Note the difference between honoring a mans idea (New Deal, Point a Minute Offense), and honoring the person that had the idea (FDR, Yost).

There is a lesson there.

"I think knowing the particular way a man like Fielding Yost failed will help us find our voice when it’s our moment."

So very well said.

Comments