All or None

In 1946, Penn State was scheduled to play the University of Miami, which like most Southern teams of the time still refused to play integrated Northern teams unless they sat their Black players. At the time Penn State had two, and of them only Wally Triplett was a regular. By a team vote, PSU canceled the 1946 Miami game, an act that Triplett credits for the origins of its great 1947 campaign, when Penn State swept its regular season opponents and earned an invite to the Cotton Bowl.

The Cotton was one of four bowl games in existence, and one of three, the Rose excepted, with standing rules against Black players participating. Responding to rumors that administrators were talking to SMU about sitting Triplett, PSU captain Steve Suhey told the press “We play all or none, there will be no meetings.” Triplett played, and scored the game-tying touchdown. Though the school’s claim that this event and the “We Are…” cheer are connected is completely apocryphal, the moment is a special point of pride for the Nittany Lions.

Michigan could have had that moment a dozen years earlier, when Georgia Tech came to Ann Arbor in 1934, and over vocal opposition from campus protestors and the greater Michigan community, Fielding Yost agreed to sit star end Willis Ward. The details of this event have been covered many times, first as dug up by Dr. John Behee in his first book Hail to the Victors! Black Athletes at the University of Michigan (1974), then in the Black and Blue documentary based on his findings, and most recently and thoroughly by the President’s Advisory Committee Report on the Fielding H. Yost Name on the Yost Ice Arena Historical Analysis.

Yesterday this committee tasked with looking at whether Michigan should rename its buildings issued its unanimous recommendation to President Schlissel that Fielding Yost’s name should be removed from Yost Ice Arena. The report is 36 pages, and informs the committee’s six-page unanimous recommendation.

As someone who talks Yost history often, most recently in an interview on the history of the Big House that aired on student television, I hope to provide some context on the committee’s findings. I will refrain from adding my opinion on the building’s name until the end because next to the facts and the opinions of those more directly affected I don’t believe my feelings, colored as they are by my history of covering Yost, should carry much weight.

Committee, Report and Conclusions

The committee begins their recommendation letter with an unattributed message from a Michigan alum asking that the name be reconsidered because “In naming the Field House after Yost, the University chose to place one man's contributions to football and to athletics above the profoundly deep and negative impact he had on people of color,” and continued to do so over several opportunities to rename it.

The committee responds to this in the summary of its conclusion:

While we acknowledge that Yost had both successes and failures in his career, our historical analysis suggests to us that the benching of Ward was not an aberration but rather epitomized a long series of actions that worked against the integration of sports on campus.

The committee also lays out what it believes should be the standard for “honorific” naming of buildings, which is:

The names on our buildings constitute a “moral map” of our institution and should enshrine the values that we uphold.

By this standard they make a convincing case that Yost’s actions in the Willis Ward affair did not represent core values of the University of Michigan as they were formally stated in Yost’s time, or as they are instituted in practice today.

The committee was created in 2017 as the active arm of the university’s new review process for renaming buildings, and President Schlissel followed its first two recommendations, removing the names of noted eugenicist CC Little and crank scientist Alexander Winchell. In the future the same committee will likely be tasked with a recommendation on the honorific naming of Schembechler Hall, and the financial naming gift of the Weiser Center for Emerging Democracies.

[Hit THE JUMP]

Findings of Racism

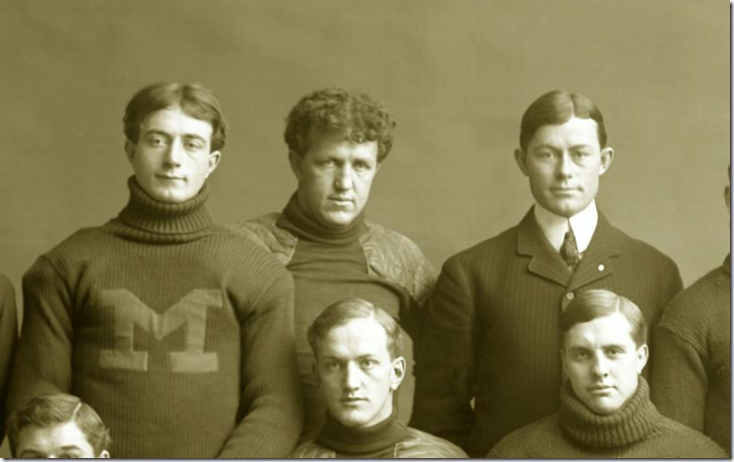

Dan McGugin (far left) was a star on the first Point-a-Minute team. He would become Yost’s brother-in-law, and but for a WWI interruption, coached Vanderbilt from 1904 to his death in 1936, upholding the Vandy administration’s color line on all of his teams. George “Dad” Gregory (center) came with Yost from Stanford, and was thereafter the subject of Stanford president David Starr Jordan’s persistent and unsubstantiated claims of cheating. Stanford recently removed Jordan’s name from a building; Vanderbilt’s athletics building today is still called the McGugin Center. [team photo, courtesy UM Bentley Library]

The report describes Yost’s background as the son of a Confederate soldier (from a Union state so this was by choice), who spent time socially in the Sigma Chi Fraternity and Nashville upper society, which he married into. They paint a picture of a patronizing “moderate” form of racism, one which was tolerant of segregation but not the violence that enforced it, as was the norm in these circles. There are few signs that Yost ever deviated from this norm.

Most of the report focuses on the Willis Ward scandal in 1934, when Yost not only chose to accede to Georgia Tech’s racist request to sit his star Black end, but hired Pinkertons to report on the leaders of the campus movement to play Ward or cancel the game. Prepare to cringe at Yost’s Michigamua nickname as well as the all-too-familiar behavior of the campus anti-anti-racism movement:

This disruptive group included athletes and fraternity members, but its core were the members of Michigamua, the supposedly secret senior honors society. The group had a very close relationship with both Kipke and Yost, the latter of whom was known as the “Big Scalper.” It is almost certain that the group had been asked to disrupt the meeting, by either Yost, Kipke, or both; in a 1942 alumni questionnaire a former Michigamua member recalling the event asked that the interviewer include “a good plug for Kipke who was behind us.”

If you consider those protesting the sitting of Ward were squarely on the side of history, Yost’s characterization of the student protestors leaves little doubt which side he was on:

In a letter to his brother-in-law Dan McGugin a few days after the game, Yost gave a literary sigh of relief that there had been no disruptions by “the colored organization and local radical students,” commenting that “the colored race must be in a bad situation judging from the number of national organizations that are organized to insure [sic.] racial equality or no racial discrimination.”

In December, Yost wrote to Georgia Tech’s coach, to “express to you personally my great appreciation of your assistance in handling what turned out to be a very difficult problem. I never dreamed there would be so much agitation about the matter.” In neither letter did Yost reveal any interest in second-guessing events, his role in them, or their impact on Ward.

And Willis Ward’s own words on the effect of the incident on himself and his team are excruciating to read:

That impact was devastating. As Ward himself later put it: “It was wrong and it will always be wrong. And it killed my desire to excel.” The same malaise struck the entire football team. Already a weak team that had lost the two games before the one against Georgia Tech, they lost every other game of the season—with Ward scoring Michigan’s only points, a touchdown and two field goals, in the remaining five games.

Ward also lost his competitive drive for competing in track, stating later that he did so out of a belief based on his brush with Jim Crow in Ann Arbor that if Hitler asked the U.S. to leave Black athletes off the 1936 Olympic team, they would. As he summarized in a 1983 interview, the Georgia Tech game “killed my desire. I said, well, I will go through the motions and play this season and get my degree and go about my business and try to get a law degree and practice law.”

There is no doubt that Yost’s actions regarding the sitting of Willis Ward were racist.

The report notes concerns held by Ward about attending the university because of stories of racial prejudice in Ann Arbor. The report demonstrates Ward’s (and really his father’s) apprehensions were well-founded, with ample evidence of racism in the actions of the university administrators Yost worked with and around, notably regarding on-campus housing, which was generating controversy for the school at the time of the Ward incident. They also found other Michigan sports when Yost was the football coach but not yet an administrator (and thus out of town 9 months out of the year) had similar or worse records of integration.

I can add from my research on Ann Arbor that several off-campus establishments of this era were particularly notorious for “unofficial” racial segregation. While anti-racism found its voice in a flourishing new campus left in the 1920s and 1930s, a large proportion of mainstream culture at the University of Michigan in that time did not differ significantly from the portrayal of Yost in this report.

Evidence that Yost’s actions “epitomized a long series of actions that worked against the integration of sports” in the report is sometimes contradictory.

Certainly the lack of any Black varsity football players from 1901-1931 (though teams were much smaller in that time) is the strongest evidence that Yost’s arrival “disrupted Michigan’s participation in the slow process by which racial integration in football was occurring.” George Jewett was the first Black player at Michigan or any other Big Ten team, but when he transferred to Northwestern in 1893 he became the last at Michigan until actions by well-meaning Michigan alumni convinced Ward to join the team.

The report notes that the lack of Black athletes on the football squad was remarked by the African American press, and that Yost’s color line, even if it wasn’t explicit, was known to the African American community, as this example from 1932 (regarding Willis Ward playing for Harry Kipke) suggests:

In 1932, when Ward made Varsity it was reported by Black newspapers “that it was the contention of many that former Coach Yost was prejudiced against the colored player” and that when he first arrived in Ann Arbor he was “alleged to have decreed…that no colored student would ever earn a varsity letter” in football.”

The report did not include one more quote I have to this effect, from former Michigan tennis player Dan Kean, a senior in 1934, who later said “If you want to know what it is was like then I’d have to say black students were AT the University but not OF it.” While evidence for a policy of exclusion was (by design) scant, Yost and Michigan had a reputation; the result of this reputation was Black athletes did not think to come to Michigan.

Yost certainly didn’t step in when basketball coach Frank Cappon refused to let Black athlete Franklin Lett try out for the basketball team. The report includes more incidents when Yost missed an opportunity to stand for justice. There’s a reference to “a simple, Anglo-Saxon desire for clean, energetic sport” by Yost’s ghostwriter in 1905 that he allowed to stand.

The report also notes Yost spoke at the Third Race Betterment Conference, organized by then-Michigan president CC Little. Yost’s words, other than a reference to the conference’s own racist title, were mostly innocuous and in line with his “athletics for all” mantra. But Yost was hardly unused to standing up to Michigan’s presidents when it came to support for athletics, and could have done so here.

The report quotes Yost’s second (there were three) successor as football coach, Tad Wieman, with this particularly noxious example of “Nobody Short of Jackie Robinson” syndrome:

There were certain complications that would be difficult for all with a colored man on the squad; that because of this I did not think it advisable for a colored man to be on the squad unless he was good enough to play a good part of the time. In other words, unless he were a regular or near regular, the handicaps to the squad would be greater than the advantages to say nothing of the difficulties that would encounter the individual himself. I assured him, however, that any man who could demonstrate that he was the best man for any position would have the right to play in that position.

There are also instances in the report when Yost’s actions showed, at least outwardly, that he was at least changing with the times. Regarding the most evident one—that Yost had no Black varsity players on his football teams for 30 years—this exchange with the African American press was interesting:

However, the lack of African Americans who played on Michigan’s Varsity football team began to be noticed in the African American press. In 1922 (the year before the Field House was named for Yost) two articles appeared discussing race in the athletic department. The first appeared in February in the Chicago Defender, which had national syndication, regarding rumors about a “color line” in sports at Michigan. The article quoted a letter from Yost to Oscar Baker, the Black alumnus and lawyer in Bay City who would later help African American students with their housing issues, stating “very positively” that “a Colored student athlete stands on the same footing as regards athletics as anyone else in the university.” Yost claimed that he “would not consider a coach worthy of the name who did not feel that the best men qualified to make up the various teams should have a place.” Both Baker and the article accepted Yost’s statements, commenting, “if the student body has Southern traditions, the same does not affect the athletic department.” A month later, the Cleveland Gazette published an article about Black Ohioan DeHart Hubbard who had just enrolled at Michigan. In it, Yost approvingly described Hubbard “as a boy they were pleased to have at Michigan and stated he intended to see that he got a square deal.”

The report found Yost supported a “Law and Order League” in Nashville whose purpose was to prevent lynching, and they found other Black athletes who participated in football despite not making varsity, undermining the link between Yost’s views and Tad Wieman’s remarks. They found Yost, upon becoming athletic director, cooperated in the recruitment of Black track star William DeHart Hubbard, citing Behee’s characterization of this as motivated by competitiveness. And they found public support (one time) for an organization that helped local Black families, and an antipathy for anti-Semitism and support for Jewish athletes that was somewhat remarkable for his time and place.

Errors, Omissions, and Criticism of the Report

For the most part, the 36-page report is a fair and comprehensive account of the consensus historical knowledge of Yost’s record on race. But there are a few significant problems with it, and I also have some questions about their conclusions.

The report makes numerous references to works by Dr. Tyran Steward, a former UM lecturer (and Ohio State Ph.D.) working on a book about Willis Ward, but does not mention another famous Yost incident from Steward’s research that conflicts with portrayal of Yost, this from 1932:

Although Big Blue relied on the Palmer House Hotel for lodging through the years, the hotel’s management was unreceptive to the requests made by Kipke for Ward to stay there. When they declined to alter their policy, “Yost flip-flopped from being a segregationist.” Ward remembered Yost saying, “Well, we have been staying at this hotel since 1900. We will pull every team that we have and not stay. . . . And I am going to see if I can’t get other Big Ten schools to also not stay at your hotel.” Officials at the Palmer House Hotel relented.

Most of our modern discussion of the Willis Ward incident, in fact, draws heavily on the research and conclusions of Behee in his first book. Behee is a friend, his recent book Coach Yost: Michigan’s Tradition Maker comes recommended by myself and Craig Ross on this site, and Behee has contributed an article on Yost for our Hail to the Victors 2021 magazine this summer. He was not contacted by the commission. Other experienced historians like Dr. Steward, John U. Bacon, and John Kryk who have written books about Yost, can give you a stronger answer than I can, and probably could have done better than the report. So could Greg Kinney and Brian Williams at the Bentley Library. Greg Dooley, the program’s historian in chief, was not even referenced in the report.

The report explicitly drew from familiar works of these historians, though to my knowledge none of them were informed their writings were being used for this purpose, nor that the committee was considering removing Yost’s name from the hockey arena. I believe the committee erred in not seeking feedback from these experts before publishing their recommendation, as this can be interpreted as disinterest in interpretations that do not fit the committee’s conclusions.

I also found one important note was misrepresented in a way that may have played a role in the conclusion. On Page 26 the authors write:

There was some precedent for that hope. McGugin had told Yost how when Ohio State played against the segregated Naval Academy, a Black player, William Bell, was not permitted to play against the Midshipmen in Annapolis, but was allowed to play the following year in Columbus. The Vanderbilt coach had also claimed that he had been willing “not to make any particular point [about playing against Bell] as we were going to their field” in 1931, but he had been overruled by Vanderbilt’s Board of Trustees.

While Ohio State did allow “Big Bill” Bell to play in the return game against Navy in 1931, they only did so because the Naval Academy, under its new head coach Edgar Miller, changed its policy in the interim, a fact that McGugin explained in his letter to Yost (see Benching Jim Crow: The Rise and Fall of the Color Line in Southern College Sports, 1890-1980, by Charles H. Martin). Ohio State benched Bell in the 1931 Vanderbilt game prior to the second Navy title, and in all three of those games deferred to the visitors’ requests. By 1934, Ohio State had hired a new coach who reinstated the color barrier for the rest of the decade, refusing to even let Jesse Owens try out of for the football team (their administration wouldn’t let Owens live on campus either). Yost’s diffident approach in the leadup to the Georgia Tech game was probably seen by him as a softening of OSU’s example.

This is part of a greater failure in the report to contextualize Michigan’s racist performance under Yost against norms for similar schools of the day. I believe this failure is mostly due to a lack of information, not willful ignorance. The report makes reference to only three other studies, two by Ivy League university presses and one by Stanford. The latter (the link in Michigan’s report is broken—the report can be found here), ironically concerns Stanford’s founding president, David Starr Jordan, who in addition to being a leading eugenicist was Yost’s greatest contemporary critic. Michigan knows much more about its racist past in the early 20th Century because we have authors who’ve studied it; few other schools have partisans so willing to look under the hood.

One line of evidence they did not follow but could have used to enlighten Yost’s racial attitudes was his relationship with other important figures at the university in his time. Yost was close with his immediate predecessor Philip Bartelme, his former player and team manager, and athletic director from 1908-1921. Yost was also often in contact with 1910-1913 baseball coach Branch Rickey; Yost trusted him enough to hire Del Pratt and then Ray Fisher on Rickey’s recommendations. Bartelme left Michigan to join his good friend Rickey in Major League Baseball, where Bartelme scouted and Rickey signed Jackie Robinson. It’s a fact that Michigan had no Black baseball players from 1883 to 1923, at which point Yost supported Rudy Ash’s joining the team, under Fisher. Yost’s close association with two men involved in the most famous desegregation moment in sports history is worth at least exploring, especially since their own records at Michigan are hardly better than Yost’s.

There’s little doubt Yost had the power and opportunity in 1934 to support Willis Ward had he chosen, or that some actions by Kipke and associates could be interpreted as carrying out Yost’s will. The report claims Yost was “disappointingly enabled by” 1929-1951 president Alexander Ruthven and members of the Board of Control, though concludes that “our research convinces us that he must bear the responsibility for the actions described in this report.” It is interesting that contemporaries who sought to change Yost’s “cowardly plan” addressed themselves to Ruthven. This could have been because they saw Ruthven as more receptive to their pleas, but could also indicate a balance of power. I also find it interesting that Yost’s most progressive acts (and indeed his hiring as athletic director) took place during the 1920-1925 tenure of President Marion Burton, who was by accounts Yost’s only true ally and friend among the presidents he served under. A more thorough understanding of Yost and other power figures’ relationships and spheres of influence might allay doubts as to which figure bears the brunt of responsibility.

I did not think the evidence in the report supported one of the conclusions, that Yost “endorsed the view that football was an Anglo Saxon sport at a time when that identification carried powerful racial messages.” It’s certainly easy to point at the 1905 book and say “It’s got his name on it.” However the footnote in the report is correct in that consensus historical opinion holds Yost was unlikely to have contributed that line:

Yost was listed as the author on the book’s cover, but the text likely came from Charles Van Keuren, a Michigan alumnus who sought to capitalize on Yost’s fame to boost sales. Per their arrangement, Yost would supply the copy, play diagrams, and team photographs, while Van Keuren supplied the text. Thus, who penned those words is unknown, but Yost clearly did not strongly object to them.

The report also misses some important context by ending its story with Yost, which was absolutely not the end of racism in Michigan’s football program or athletic administration. Fourteen years after the Willis Ward affair, the fall after the Cotton Bowl and SMU quietly backed down after a Penn State player said “all or none,” Gene Derricotte was the only non-white player on Bennie Oosterbaan's 1948 "Mad Magicians" team, which repeated as national champions. A decade later the roster had expanded considerably, but Michigan still only had three Black players on it. Behee’s book has direct evidence that after “integration” Michigan participated in an unofficial quota system that kept Black participation to just one player per class until 1968, an effect you can literally see in the 1969 team photo:

I don’t think more examples of racism in Michigan Athletics in any way exonerates Fielding Yost for his actions. To the contrary I think these examples underline the severity of it, and how deeply rooted, though quiet, these practices were, and therefore how righteous and necessary the campus activism of Black students and their allies was to effect change.

My Interpretation

Michigan named the rink for Red in 2017. [Bill Rapai]

I speak here for myself, not for MGoBlog or anyone else who works here. I’ve studied a lot of Michigan history from before, during, and long after Yost, and from that I can say with some authority that racism at Michigan neither began nor ended nor changed much on account of Yost.

The Crisler era that followed was marred by unofficial quotas to keep Black players to a minimum. Schembechler made it clear to his players they were to stay away from the successor movements of the social justice activists of Yost’s time. When I was at Michigan in the early 2000s and the school’s admissions policies were national legal news, the College Republicans were given permission to set up in Angell Hall selling “Affirmative Action Bagels” that were $1.00 for white customers and 10 cents for Black students. I doubt any Black student in the history of the school has ever made it through their scholastic career without at least some racist incident on campus. Racism at Michigan isn’t some nebulous problem of the past. It’s our reality today.

How does it happen? Read the report. It’s a culture, a cancer, and nothing would have changed if there hadn’t been people who cared more about justice than whether “polite” society gets smacked in the face.

As for Yost’s culpability, of course he knew he was wrong; why else would this man who loved the limelight suddenly shirk it? Why else would the most competitive man of his era sit one of his best players, or a coach whose entire style was about building up confidence undermine his team? That this was not unusual for a man of his times who mostly changed with his times does not dismiss his failure. He no doubt failed to meet the moment when Michigan played Georgia Tech in 1934, and his subsequent actions to defend his decision rightfully earn him censure by future generations. This was the definition of an “I don’t see what the big deal is”-style racism that allowed that culture to flourish then and survive today. Placing the blame for the effects of one’s moral cowardice on “radicals” and “agitators” had miserable precedents then and more today.

Yost’s upholding of the “gentleman’s agreement” is evidenced enough in the makeup of his teams. If we all take away nothing else from this report, I want us all to understand this is how racism works. It’s not the things that are said aloud, because the whole point is not to have to say anything. Black athletes knew not to play for Michigan under Fielding Yost. When one man finally did, his worst suspicions were confirmed. Yost made racist decisions, and I’ve had no problem saying so when I talk about his contributions to Michigan athletics. I do not find him in any way remarkable in this regard from other athletic directors of his era, and I have no problem with calling out the lot of them if it helps us move past the decision cycle.

I find attempts to place one man on this curve, with “Okay, you can keep your name on your building” at some undefined point along it, to be a shallow exercise for people who want easy labels. The whole society was racist, but inside of that you had some people trying to change things for the betterment of us all. It’s better that we named the renovated room in the student Union after Willis Ward, and that Michigan and Northwestern are choosing to honor George Jewett. Whatever you do with Yost Ice Arena, find something to honor Joseph Feldman, William Fisch, and Danny Cohen, the names of student ringleaders Yost’s Pinkertons gave to President Ruthven, and who were quietly dismissed in July 1935. Without those three the next administrator faced with this question would not have feared a backlash, as Yost didn’t after the example of Ohio State. Whatever they do with Crisler for the quota system, I think we need to honor the few guys who did come: Guy Curtis, David Raimey, Bennie McRae, Jim Pace, Bob Marion, Lowell Perry, Gene Derricotte, and more who had to be greater than great, and carry the reputation of millions with their own.

I believe Willis Ward that Yost’s decision ruined him and the team, as I believe Triplett that his teammates’ support motivated their great 1947 run. I believe that this extends to the Michigan community and greater society, which becomes energized when we stick up for each other, and demoralized when we don’t.

I personally don’t have much care for what a building is named. I have great memories in Yost Ice Arena, and they won’t be affected if it’s renamed Berenson Ice Arena, because most of those experiences were thanks to Red’s teams. If years from now history shows Berenson failed in his moment, they can change it to Hughes Arena to honor the 30 first rounders that family sent here.

I find most conversation around honorifics either obvious or boring, and this one falls in the latter camp. C.C. Little got a building because they noticed all but two presidents—Little and Ruthven—weren’t going to have buildings so they found a pair. Winchell got a house because they needed nine former professors with long tenures. You spent more time reading this than the people who named those spent on their subjects. It’s an easy call.

Yost Ice Arena is not. It’s a balance. The Field House was named after him because he invented the concept, and the name was bestowed after another contentious fight between the faculty who found Yost’s zeal for athletic competition distasteful, and the regents and alumni who were all about the football. His association with hockey is equally earned; Yost raised the hockey program to varsity status in late 1922, and in 1928 he purchased the Weinberg Coliseum they’d been renting, renovated it, and filled it with artificial ice, just before the Depression hit and ended all the building projects. His impact on campus was such that I could make a similar case for almost any sport, and his impact on women's athletics at Michigan is second only to the passage of Title IX.

His impact on Black athletes and would-be athletes who never got a chance to play at Michigan may not have differed from an average man of his time, but it was manifest. When nearing the end of his career he had a chance to demonstrate his growth, Yost chose to duck. That is now as much a part of his legacy as the buildings.

I believe the racial issues at Michigan in Yost’s time were systemic, and while it’s fair to hold one man accountable for his role in that system, wiping his name from the building is a performative gesture, not a remedy. More than a name, I think there should be a bronze placard outside the arena, telling the Willis Ward story where people waiting for their friends will read it because it’s too cold to hold a phone in your face.

I’m less thrilled about the standard that “The names on our buildings constitute a ‘moral map’ of our institution.” I think this runs the risk of making honorees two-dimensional, and will lead to more icky donor names that are harder to correct. History is not a moral map. It shows us where we’ve been, what choices led to darker paths, what perils might lie along the way, and how we’ve corrected mistakes.

More than anything I think that the 36-page report produced by the advisory committee is something every Michigan fan should read, especially if you choose to comment on this after. More important by far than the measure of one long-dead man is that we gain a better awareness of how regular living men and women contribute to racism at the University of Michigan, and how being a part of this society has soaked the stench of it into all of us. If you’re pointing to one guy and saying “He’s a racist (and because I’m pointing I’m not),” you’re missing the point.

I think the story of Willis Ward, and the context it happened in, are relevant today. I think his heroic choice to rebreak Michigan’s color barrier should be celebrated, that the efforts of his recruiters should be recognized, that people should know if not for Harry Kipke those recruiters probably wouldn’t have even tried. I think we should honor the heroic voices of activists of the past, and that the righteousness of the causes they agitated for are instructive in how we regulate our annoyance at their successors’ insistence we face our facts. I think knowing the particular way a man like Fielding Yost failed will help us find our voice when it’s our moment.

If it were up to me, I'd rename it after Gerald Ford.

Bu bye MGB

go tear down some statues or whatnot. The sanctimony that goes into passing such judgments on defenseless, long passed generations, is incalculable.

meanwhile we seem to have a great basketball coach, a formerly innovative but damaged football coach, and now a dysfunctional blog that somehow sees itself as a social justice beacon in a world where every gosh damn thing we do is politicized.

But hey let’s pound on Yost, so courageous!

Peace out

I appreciate the mostly respectful dialogue on this forum about a complex and difficult topic. It is refreshing to see that people with differing views can engage in discussion without the all to common practice of shutting out ideas and reducing complicated human existence and society to simple labels and if/then equations. As to the Yost building, I am personally conflicted about the renaming prospect but favor keeping it. For me, the name and building represents the shared experience with other students and fans during my undergraduate days of UM sports fandom. That thread runs forward into later adulthood and continues to exist as part of this blog, as we are inheritors of Yost's legacy by celebrating Michigan athletic excellence. However, I recognize that we also inherit his legacy of participation in racist practices and further that his name may specifically remind others of some of the terrible manifestations of it in his time and still in ours. Isn't there a way to reconcile both? Many today would say no, but I disagree. Can't we keep the Yost name for the good parts it represents and still address the legacy of racism? That could happen by naming a new building for a minority hero, or erecting a new statue of a civil rights leader in front, or something else that shows love and reconciliation not anger and destruction. As others have written, we are all flawed humans-- each of us has only to review the last week of our personal lives to find examples of anger, impatience, unkindness, bias, rudeness, hostility, greed, pride, slander. I know I certainly don't deserve a statue or building name, based on my behavior at home even last night. I look to Yost and Michigan athletics for community and enjoyment and for aspiring to something greater than my individual shortcomings. Let's do that by having these discussions, by creating healthier society for all participants. I think it is more powerful for Yost in 2021 to represent a thread of community uniting us all-- in our difficult past moving toward our difficult future. Yost the man's time is gone, and now it is our responsibility to shape what it means to be a community of Michigan fans. Yost the building's time continues on: I would rather witness change in what that represents than attempting to lose touch with the past.

Great column by Seth, especially the point about the zeitgeist of that period of history as regards race. Far from supporting the committee’s case for removing Yost’s name from the arena, it poses the question of whether Yost was merely the expression of a common viewpoint at the time.

That brings up bigger stakes that I don’t think the administration wants to wrestle with because it implicates the entire administration as enablers since they hired Yost and continued to employ him. The logical extension of this premise is then that maybe the administration should consider removing all named buildings from that time period to avoid the appearance of selective judgement.

Ironically, this is why that premise is flawed to begin with. The committee and the administration appear wedded to the idea that only Yost was culpable, and do not want to offer up anyone else as a sacrificial lamb. That’s really a coward’s way out. Either indict all of Yost’s contemporaries at Michigan as a part of the problem, or spare them and admit the obvious, which is that societal norms at the time were different . We can still acknowledge how those norms don’t stand up to contemporary ethical foundations of decency without condemning people of that era for not holding views common today.

If however this is the standard that we are going to hold benefactors to, we ought not to extend naming rights in the future. The cost will come in forgoing the benefit that naming rights play as an incentive to donate and as an example that inspires future philanthropy.

Comments