Neck Sharpies: Mad Magicians at the Super Bowl

SPONSOR NOTE: Upon Further Review is sponsored by HomeSure Lending and Matt Demorest. Mortgage rates are LOW right now, so if you've been waiting for the right time (read: after football is over) to see if refinancing can save you a bunch of money, now's a good time to strike. It usually takes Matt and his people about 5 minutes to know if a refi makes sense, and if it doesn't they'll tell you. You know the guy, and you know from a bunch of other readers that he does a better job and charges less than the mills that use the difference to buy Super Bowl ads and other peoples' basketball coaches.

SPONSOR NOTE: Upon Further Review is sponsored by HomeSure Lending and Matt Demorest. Mortgage rates are LOW right now, so if you've been waiting for the right time (read: after football is over) to see if refinancing can save you a bunch of money, now's a good time to strike. It usually takes Matt and his people about 5 minutes to know if a refi makes sense, and if it doesn't they'll tell you. You know the guy, and you know from a bunch of other readers that he does a better job and charges less than the mills that use the difference to buy Super Bowl ads and other peoples' basketball coaches.

-----------------------------

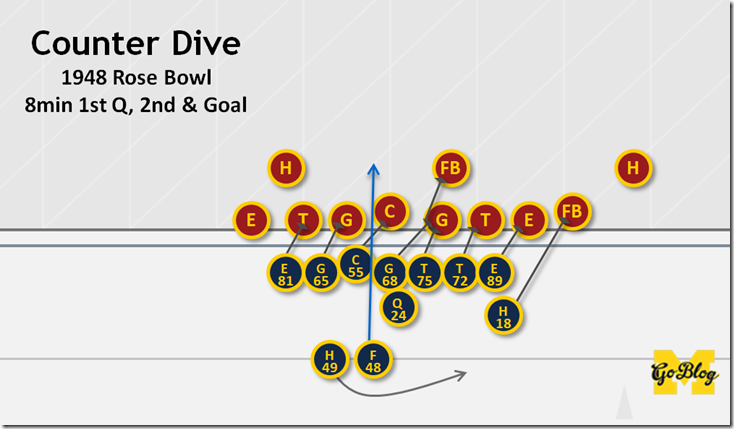

You might have heard by now the play that Kansas City ran on 4th and 1 was right out of Fritz Crisler's Mad Magicians tape. Here's the old Michigan play, captured in the 1948 Rose Bowl:

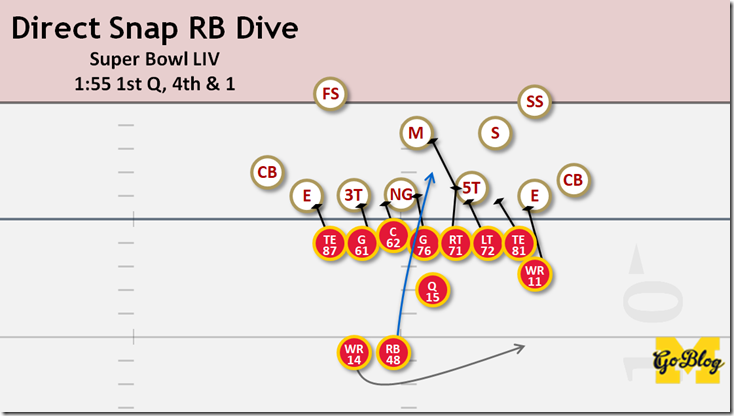

And here's the Chiefs play from the Super Bowl:

Here's Chiefs offensive coordinator Eric Bienemy copping to where he got it from:

Chiefs OC Eric Bieniemy on spin move trick play to convert 4th down vs. 49ers pic.twitter.com/wpOxC1DJMV

— James Palmer (@JamesPalmerTV) February 3, 2020

And thanks to John Kryk (Stagg vs Yost, Natural Enemies), we also know where Reid found it—his high school coach played for those Trojans:

Andy Reid was asked where this play cam from. 1948 Rose Bowl Michigan vs. USC. #spreadoffense #ChiefsKingdom pic.twitter.com/NIvIxNNX01

— SpreadOffense.com (@SpreadOffense) February 3, 2020

And I'll add it's not the first time KC ran a Magicians' play.

While my shiny medal for pointing it out first makes its way through the mail, the Bienemy quote has generated a small cottage industry of writers linking the two together. Views of the Sap version, the Wolverine Historian video, and the copy of that set to "How You Like Me Now" were duly plundered to show them both side by side and talk about where the ideas come from. If you read just one, I'd recommend Kryk's in the Toronto Sun. If you read two, Alex Kirshner of The Banner Society incorporated Fritz's playbook and some history.

All that's left is for one of the internet X's and O's guys to draw it up, explain how Fritz Crisler (and Bennie Oosterbaan)'s offense worked, and why it's such a nice complement for Andy Reid's offense in 2020.

[After THE JUMP: Why we wing]

Why This Formation?

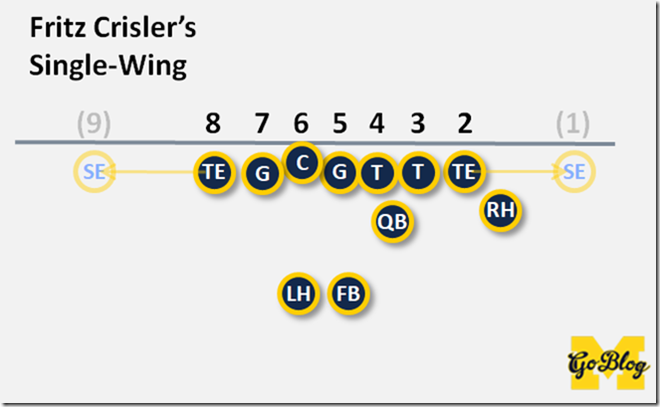

You're looking at the Single Wing. Since we have Crisler's 1947 playbook we know how he ran it. If you care, he numbered the linemen from the strongside, with the ends able to "split" to a 1 or 9, or remain "tight" in a 2 or 8. They could line up the backfield "centered" (the fullback behind center, quarterback behind the guard) or "shifted" as shown below.

This was one of the most popular offenses from the early 1900s, when when Fielding Yost forced everybody to get more creative than plowing ahead from the T formation, up to the 1950s, when the new rule allowing pocket passing sent everybody back to the T formation.

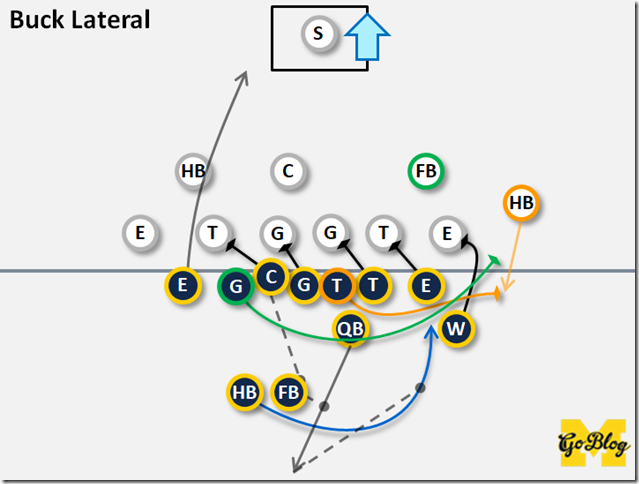

You'll note it's unbalanced, with the left tackle moved over to the other side of the formation. The quarterback is nestled behind the guard. Even the fullback is shaded a bit to the right side. These are all clues to the point of the single-wing: bring a mountain of humanity down on the right or "front" side. Here's an example from 1949:

(gray dotted line is where the ball is passed)

Imagine a typical snap to the halfback here: he's moving right with three lead blockers (not counting pullers) and six gaps his momentum can immediately threaten. The linebacker hanging out there has all kinds of blockers coming his direction, as well as a threat outside he has to be wary of. There are just so many potential blockers coming from so many angles on the frontside that you have to be locked in, know your role, and stay disciplined as all hell breaks loose.

This also has the effect of clearing out potential defenders from the back side, where you can isolate their halfback against your star, or leak your end into the seam for a quick pass between the run-stopping obsessed center and a safety who has to hang way back there in case of a quick punt.

The key to running this offense—according to Jack Weisenburger, the starting fullback for Michigan's 1947 Mad Magicians—was a center who could snap it accurately to any spot in the backfield. This is because he has be able to snap it to an exact spot on the knee of any of three potential backs. The quarterback can turn in and accept it facing to the backside, in position to hand it off to either back coming to the A-gap on a dive, flip it outside, or run it himself. Or the halfback or fullback can get a direct snap, run out of the tackle box and throw it, or spin and hand it off.

The base play from this formation was to direct snap it to the left halfback or "tailback," pin & pull the across the line, and use the rest of the backfield as lead blockers. Most plays however snapped to the fullback, who pivoted (hence the term "spinning fullback") around to threaten runs in various directions. To this backfield coach Bennie Oosterbaan, who would take over as head coach in 1948, added all kinds of misdirection and backfield frippery. Readers of MGoBlog will recognize the blocking, if not the insane backfield action, from the rushing offense Michigan's been running lately:

Many gray dotted lines (safety would be set up at punt return depth)

This is not the play the Chiefs ran. Take out the frippery and it's a pin & pull. It is the base play from the formation they ran it from, the way Power-O is the base play from an I-formation, inside zone is the base play from an Ace, and Zone Read is the base play for a shotgun offense (imagine that quarterback split out as a wide receiver instead). It's the play that's going to get you 3 yards every time if you execute it and the defense isn't doing something unsound to beat it.

Why the Pre-Snap Frippery?

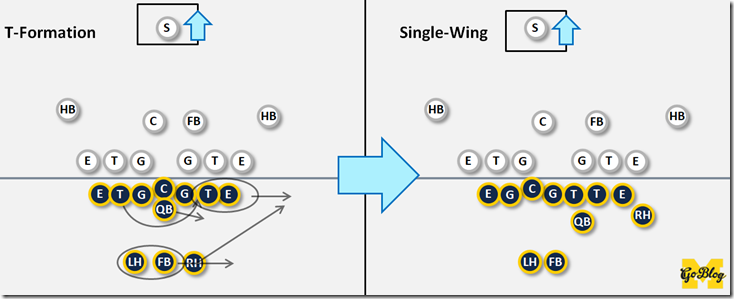

Shifting into a Single-Wing from a more base offense like the T-formation (or later the Box T formation popularized by Notre Dame in the 1920s) was part the strategy almost from the beginning. The reasoning for this goes back to all of those gaps on the frontside: it's hard for a defense to get all of their assignments correct to begin with. Now you're adding a gap and putting them to a decision to either be outmanned to that side or be unbalanced as a defense. But give them enough time to point and communicate and a good defense should figure it out, especially if they're used to defending single-wings, or professional defensive players in 2020.

I think it's most helpful to see it shift from a T-formation because it mimics the base play they're essentially shifting to:

Imagine this shift happening after the snap. You've got a backside puller, an H-back (or Wingback) flaring out to the edge, and the rest of the backfield shifting in the direction of the play. In essence: a run to the right. The Single-Wing is a great big load-up to run to the right.

To speed this up the offense would usually come out with the linemen already in place, having them stand up and go back down during the shift. As the defense is trying to communicate with each other about the unbalanced offensive line, they're suddenly distracted with some fancy movement all over the backfield that messes up the assignments they were just handing out.

(Bonus credit here to the Chiefs for their initial diamond setup from deep in the game's history. If you've ever wondered why the backfield positions are called what they're called, find the back lined up a quarter of the way into the backfield, the two who are half-way back, and the back who is fully back. Once they've shifted you now notice a back on the wing and another off to the fullback's side, and positioned to run behind him, like a tail. Also the defense's halfbacks are arranged on the corners. Etymology!)

Anyway the shift isn't strictly necessary but it's helpful in generating the confusion and disarray in the defense when the trick to stopping the Single Wing is—you guessed it—playing disciplined, assignment football. Back when this was all the rage defenses didn't think as much in terms of gaps as men, since you were generally playing mano-a-mano in the box all the time (the need for two safeties in the 1970s and '80s is what changed the math and led to gap defenses). This was all the more true close to the opponent's goal, when punting was no longer on the table and the safeties could stick their noses back into your run game. Screwing up what they're looking at before you threaten a forest of gaps is even more effective today than it was in the Single-Wing's heyday.

As for the pirouettes: first it's fun and they're in the Super Bowl. Second it's a timing thing. As long as the backs and linemen are moving, #11 sneaking out to the wingback position doesn't become the focus. You really want them to notice that guy at the last second and flip out that they don't have the extra gap out there covered. Ideally a linebacker sees that at the last second and things "Ahhhh I gotta get outside." If the guy moving out to wingback is All-American Bump Elliott and the guy threatening to swing around behind him is All-American Bob Chappuis, all the more reason to freak the hell out.

Okay So What About the Play Itself?

It's really just a simple counter dive. If you watched a lot of football in the 1990s you've probably seen this play a hundred times as a fake toss to the running back and then a fullback dive into the A-gap.

The formation and movement and the counter action by the left halfback (Heisman candidate Bob Chappuis) are all telling the defense they have to defend the gaps to the right of the center. Everybody starts blocking that way at the snap and that too convinces the defense they have to jam this up. In the middle of all of this is a double on the frontside guard (today we'd call that a DT), a battle Michigan's right guard, Stu Wilkins, and star left tackle Bruce Hilkene are more than capable of winning against some puny Pacific player. Center JT White cuts USC's center (this meant linebacker on defense) and fullback Jack Weisenburger's momentum carries him through the backside A-gap.

The Chiefs play downloaded many of the same elements:

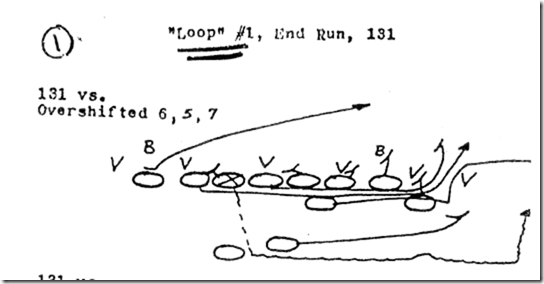

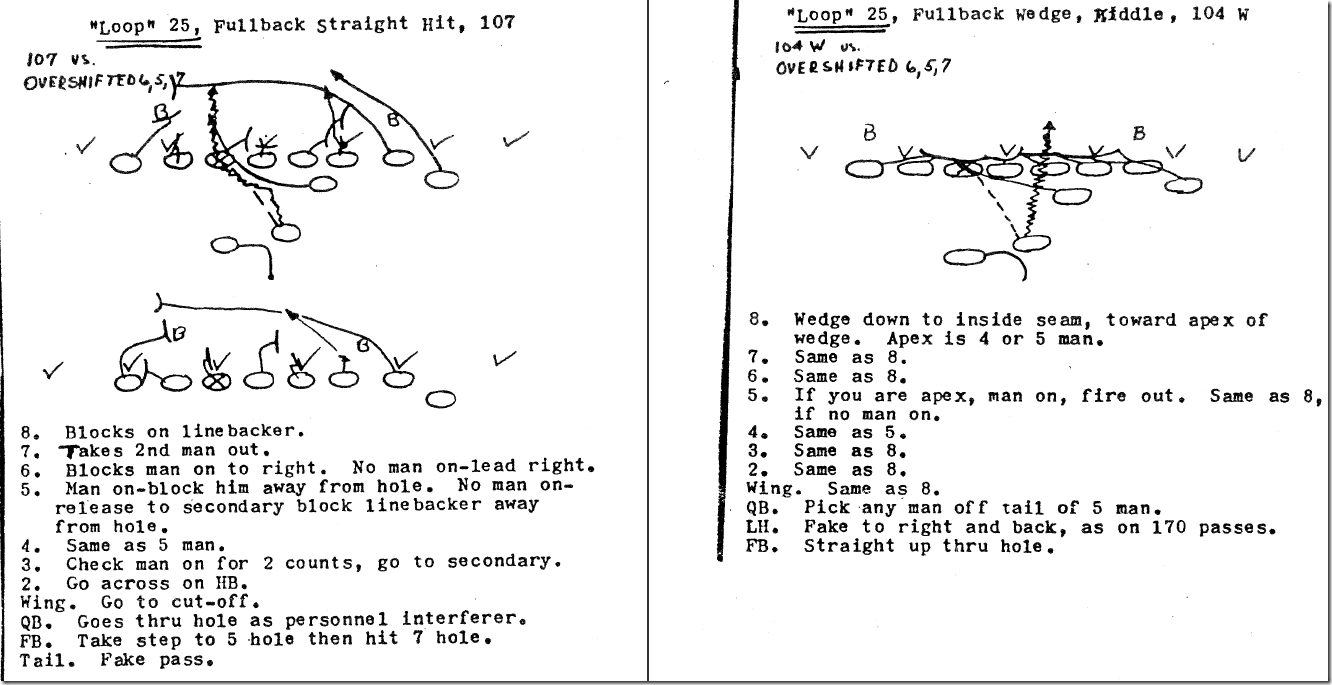

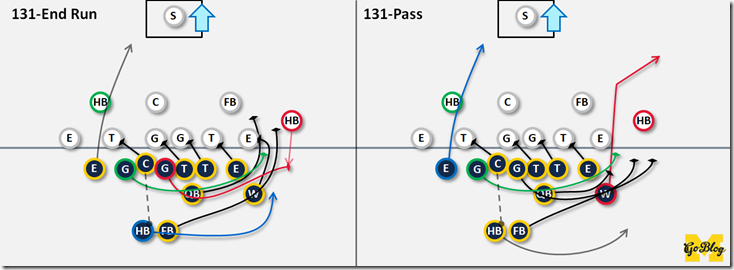

The first difference you'll note is the blocking is different: the Mad Magician is blocking down left-to-right to run to the left of the center while the team from Missouri is coming down right-to-left. If you go into Fritz Crisler's playbook from 1947 (link) you can see he has something like this set up to run to either side (may have to click to read it):

The one on the left, "107" is a counter with the back hitting the backside gap. It's more or less what they ran against USC. The one on the right is almost exactly what the Chiefs ran. The concept is the same: double the frontside tackle down to the linebacker and quickly pop through a gap behind it as the line gets washed one way or another. Which way is just a call based on how the defense aligns and whether you think they're going to slant this way or that.

Another difference is the quarterback received the snap in the 1947 edition. This was almost certainly a tweak put in for the bowl game, as USC would be keying Michigan's goofy Buck Lateral series when the quarterback got the ball, and would be likely to go chasing the tailback outside rather than reacting quickly enough to get to the fullback coming downhill.

The 49ers on Sunday night weren't reacting to half a century of Single Wing ball based on direct snaps to the running back. This all looked goofy, and those who missed the direct snap to the running back could be confused by the action of Sammy Watkins, playing the role of left halfback, and the pantomimed pitch to him outside. Indeed, it freezes the SAM linebacker who could have dealt with this, which probably has a better chance of success than Mahomes—athlete though he may be—lead blocking.

Crisler Would Have Liked Reid

Crisler was indeed one of the best coaches of the Single-Wing school, but also one of the last. His playbook is one of the more complicated of the genre, and plays off of half a century of defenses training to stop this offense. Base power runs to the wing's side would be like running zone reads as your base thing today—everybody's well-versed in stopping it, everybody's well-versed in stopping its base constraints, and innovation is all about how to reopen those constraints by threatening the responses baked into modern defenses.

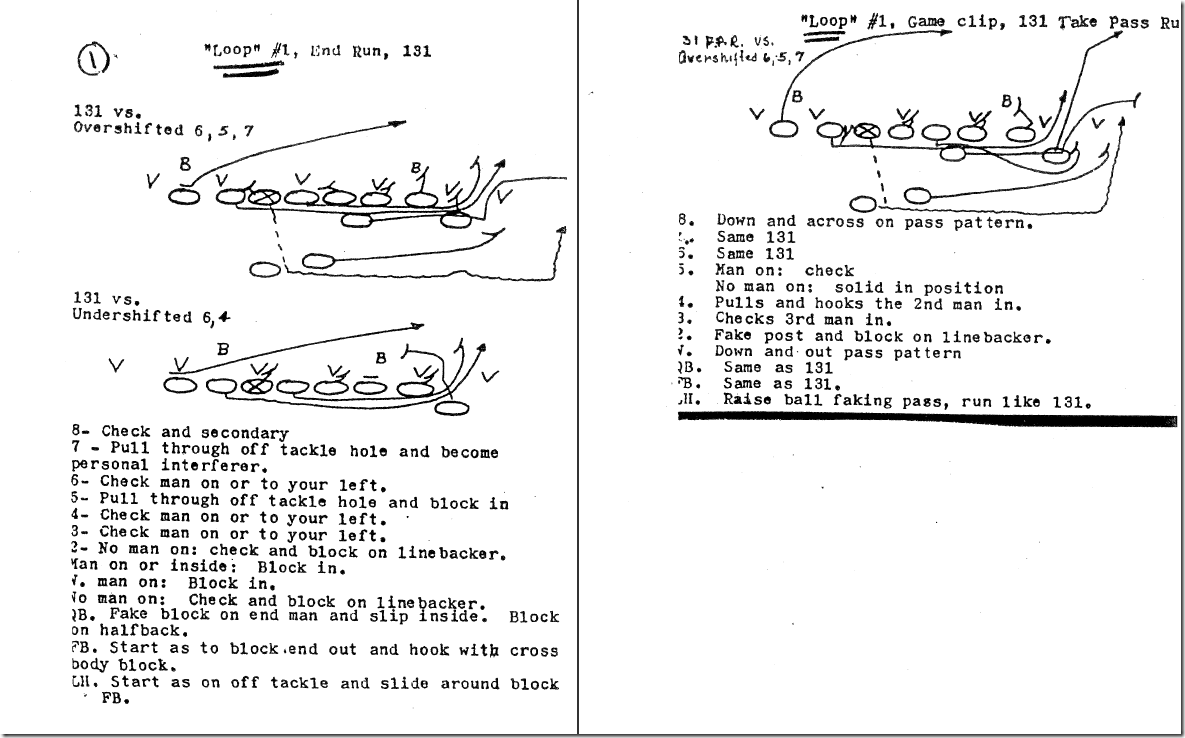

And that's really what Crisler mastered: constraints. Here's the first page of plays, featuring that base outside pitch with all the pullers. Remember you can't pass from within five yards of any direction from where the ball was snapped at this point so all passes are rollouts.

click for big

Note all the "same 131" instructions on the right-hand play. There's a recorded description from Michigan's side when they played Crisler's second Princeton team during Michigan's 1932 national championship season. Princeton was still built to be a dive and dive again team, but Michigan's star center (middle linebacker) said they were so tough to play because "Everything looks like something else."

Look at the design of these two plays and how they mess with the halfbacks (cornerbacks):

To stop the base run the backside HB has to get on his horse and beat the last puller to the point of attack, and the frontside HB has to pinch into the backfield to find the puller trying to kick him in time to constrict the lane. Every second lost is a yard. Oh, and by the way, there's also a pass play that looks exactly like this where those two HBs are responsible for covering 1949 NFL receiving yards leader Bob Mann and 1947 All-American wingback Bump Elliott.

As you've probably guessed, the play the Chiefs ran had a constraint too. It's not in the 1947 footage but you can see Oosterbaan's 1950 team running it at their next Rose Bowl:

Constraints are ubiquitous in football, but 75 years ago if you were to name the guy in football with the most innate understanding of how to keep defenses consistently punishing themselves against your playcalls it's Fritz Crisler, and if you were to name someone today it's probably Andy Reid. Both Reid's "pro style" offense with fullbacks and base under-center formations, and Crisler's Single-Wing were past their heights of popularity, almost novel in an era that had mostly moved on. Both function on similar principles: you can attack very well at a certain spot in a certain way, and you use constraints and players with multiple skills to punish defenses for over-committing to that.

Both also have to thank a brilliant assistant. The surviving Magicians I've spoken to all gave a ton of credit to Bennie Oosterbaan, specifically for adding the funky stuff in the backfield. The quarterback called the plays in those offenses (no they didn't use options, even if sometimes it looks like it), and the quarterback was coached by Oosterbaan. In the same vein, the Chiefs' Eric Bienemy is a master playcaller, and long past due to get his shot as a head coach.

Does This Mean the Single-Wing is Making a Comeback?

Whoa whoa whoa, it's a good goal line offense, sure, but there's been some considerable advancement in offensive strategy since WWII, and the one of the major issues the Single Wing was trying to solve—how to use passing as a threat from your base offense when you're not allowed to throw from the pocket—hasn't been applicable since two years after the offense we're talking about. Crisler and Oosterbaan's Mad Magicians were the best of the Single Wing offenses, but even they were becoming obsolete.

Many elements of Single-Wing football are still around today, especially in power spread offenses that Gus Malzahn and Urban Meyer developed—offenses predicated on the getting numbers. Bits of the Mad Magicians' backfield action survives in jets, reverses, and BASH concepts.

However a pro team bringing it out for a surprise and somebody using this as a base again are very different things. NFL teams have way more practice time, and since timing is so important to this offense you need a lot of it to install. Personnel acquired for modern passing spreads don't fit so well into this system. And good luck finding a coach willing to use his quarterback primarily as lead blocker.

History junkies like me will always advocate for more stuff out of the vault. It's great to spring old stuff that no defense has practiced against in three-quarters of a century. There's way more value in old school football that most people credit, and it's nice to have a chance to point that out sometimes. At most you could make this into a goal line package. Or a silly way to pooch punt.

February 4th, 2020 at 12:15 PM ^

Reid said they have a whole package they're going to use next season!

February 4th, 2020 at 12:29 PM ^

Great post

February 4th, 2020 at 12:35 PM ^

KC Chiefs--the pride of the state of Kansas!

February 4th, 2020 at 3:50 PM ^

I did like the "Team from Missouri" jab...

February 4th, 2020 at 1:04 PM ^

There's way more value in old school football that most people credit, and it's nice to have a chance to point that out sometimes.

Hear, hear. The single wing was made obsolete by rules changes so it's not going to outpace systems designed to exploit those rules. This play was basically frippery. But there are just so many philosophies out there that a college program can't adequately drill assignment football for all of them.

The difficulty, though, is that you can't ride frippery from the past for a full season. If you dug up the offense out of a dusty tome, well, the other guy can just as easily look up the answers in the same book. That'll beat schools that can't recruit the personnel to defend both, but a school like Ohio State and its army of five-star athletes (sigh. . .) can match any opponent in either power OR speed.

February 4th, 2020 at 1:43 PM ^

Seth, this is some really good stuff. Thanks for putting this together!

February 4th, 2020 at 2:22 PM ^

Thanks for this! I was wondering why this was such a "trick play". One question--in a typical game, backfield motion (1 guy in motion, everybody else is set) is common, yet formation shifts (everybody unsets, and then sets for the required second) are incredibly uncommon. Why don't we see as many formation shifts like this to confuse the defense?

February 4th, 2020 at 2:48 PM ^

I'm no one's idea of a football expert but I'd presume it's the return on investment of practice time. Practicing a play by itself is labor-intensive. An improper shift can result in a penalty, so that's added practice time, just for that. That's one play and one shift.

To make a shift/play combination anything other than a one-time gimmick (probably the most inefficient use of practice time, generally only used for trick plays when you absolutely need a yard or three), you need more than one pair. Otherwise if you're always shifting from formation A to run play B, once it's on tape (or even before halftime!) the defense will key on A and adjust to B, rendering all that time practicing the shift wasted. The goal is to make the offense unpredictable, so you'll have multiple formations, shifts, and plays. But this adds complexity to the offense -- sure you're more likely to confuse the defense, but you're also adding risk of confusing your own offense -- and an improper shift, even if not a penalty, can kill a play dead before the ball is snapped. You're not going to run a play in that state, but this means the team needs to practice until they can execute all these shifts flawlessly. For all that investment, why not take the practice time and just. . . add more plays?

That's not to say shifts aren't worth the trouble. The point is that they're not free. They have costs in terms of practice time and complexity, so getting your money's worth out of them isn't always straightforward. The KC Chiefs are an NFL team so they get way more practice time than college programs, yet this still more in the "gimmick" territory (although one of Seth's cites implied they're actually working on a set of similar plays). And college football was a very different beast back in the 1940s -- I don't think the Mad Magicians had the NCAA breathing down their necks about excessive stretching. Today's OCs need to carefully consider how much deception they're going to bake into an offense, especially at the college level.

February 4th, 2020 at 2:46 PM ^

Thank you KC Chiefs for providing a wonderful riposte to the oft-repeated slight on Michigan's older achievements.

February 4th, 2020 at 2:59 PM ^

I was hoping for a Super Bowl edition of Neck Sharpies! Thanks but there goes my productivity at work.

February 4th, 2020 at 3:08 PM ^

Based on the length of the player's shadows, this TD came in the early 4th quarter when M was already up 28-0 (there were three 1 yd TD runs by Weisenburger). USC looks to have given up at that point as their entire team basically just stood up at the snap. I don't think it mattered what play we ran at that point.

We needed to blow out USC to pass ND for the #1 ranking (we threw for two more TDs in the fourth quarter up 35 and 42). We also needed the AP voters to decide to hold the first ever post-bowl poll (ND didn't go to a bowl that year for some reason). Notre Dame claims and the NCAA still holds the AP National Championship for 1947 even though the AP itself declared UM the champion.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1948_Rose_Bowl

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1947_Notre_Dame_Fighting_Irish_football_team

Also, while digging through various sites I saw that in the year prior, 1946 Army was ranked #1 all season. Went 9-0-1 with their only tie being to #2 Notre Dame (score: 0-0). Army beat #4 Michigan; #11 Columbia; #13 Duke; and #5 Penn, but only beat their hated rival Navy 21-18 in the last game of the year.

Of course the AP gave ND the national championship that year having beaten two ranked teams all year: #17 Iowa and #16 USC in the last game 26-6. Lame.

https://www.sports-reference.com/cfb/schools/notre-dame/1946-schedule.html

February 4th, 2020 at 4:13 PM ^

Thanks Seth! This may be the most interesting (and understandable) neck sharpies ever.

February 4th, 2020 at 10:09 PM ^

Probably my favorite Neck Sharpie. What a cool history we've got

February 5th, 2020 at 1:33 PM ^

I absolutely love, love, love this -- because I don't think those whose memories or M interest post-date 1969 have much of an appreciation for those who preceded that year. Understandably, I guess, since few now alive witnessed the fabulous athletes we had at this University, certainly not in-person and few videos are available as well.

To see these videos, it is absolutely wonderful. When I saw that Kansas City play live, I wondered about what I saw since it was so unusual and had no idea of the connection to M. There seems to be a hint that Kansas City has more offense in this mold. Let's abandon the Lions and adopt the Chiefs!

This is all to put a plug in for a relative, Wally Teninga, who was an outstanding running back in that late 40's championship era. He was terrific and doesn't get the recognition that he would get if he was playing today. Here's to the Mad Magicians!!

Comments