Hockey Nuts and Bolts Part 1: Transition Play

Welcome back to our summer series on teaching the game of hockey. For those who missed the preliminary piece on college hockey and how the sport operates at a program level (and how it differs from the NHL), you can still read it here. Now we are about to dig into the meat of this series, which is deconstructing the intricacies of the game, analyzing how teams play, how coaches think, what strategies they employ, and how to think about hockey in a smarter way. Today we will begin by talking about offensive transition play, which comprises a big chunk of the game. Particularly, how teams go from defense to offense, how they take the puck out of their own zone and end up in the opponent's zone. Really there are four main components to talk about: zone exits, regroups, counters, and zone entries. Let's go through each.

Zone Exits

This is pretty simple. Most new possessions are going to begin when you have the puck in your end. Maybe your team just picked it up after a dump-in from your opponent. Maybe your team just got the puck after a shot from the opponent was saved by your goaltender and ricocheted to the corner. No matter the situation, zone exits are how you begin turning defense into offense, the step of taking the puck out of your own zone and moving it into the neutral zone. The raw objective here is to alleviate pressure. Simply pushing the puck past the boundary of the blue line requires the opposing team to entirely leave the zone and then tag up thanks to the offside rule. But good teams are the ones who know how to use the exit not just to alleviate defensive pressure, but to kick-start an offensive sequence.

There are two kinds of zone exits, controlled and uncontrolled. In an uncontrolled zone exit, a player on the defensive team takes the puck and simply clears it out of the zone, either by banking it off the boards and out, or flipping it up the air, past the blue line and out of the zone. This type of exit accomplishes the bare minimum, getting the puck out of the zone, and taking the heat out of a hot kitchen. It alleviates the pressure, forces the opposition to retreat, and can allow for a line change depending on situation. However, there are some drawbacks here. For one, it often doesn't result in a change of possession. In some ways, an uncontrolled zone exit is like sacking a quarterback in football: it sets the opponent back, but doesn't mean the defense gains possession. Unless the puck is flipped down the ice to a streaking forward, the opposition's defense or goalie will handle the puck and start a new possession for the opponent. That's why I view uncontrolled exits like a fire extinguisher. They have their purpose and should be used in case of an emergency, like when the opposition has just had a ~30 second offensive zone possession and the defense is tired and simply needs a change. That's when you want to flip the puck down ice and get new legs on. But in terms of creating offense and producing winning hockey, leaning on uncontrolled exits is not the way to go. Not to mention the fact that an uncontrolled exit always risks an icing, if the defensive player is overzealous with the clear.

[AFTER THE JUMP: A lot more strategy]

Thus, it is my opinion (and the opinion of most coaches) that controlled exits are key to success. Zone exits may be done by either forwards or defense depending on circumstance, but a lot of times the burden falls on the defensemen. The zone exit typically happens either through a pass up to a forward, or by having a singular player skate with the puck out of the zone themselves. Therefore, the defensemen who are elite at zone exits are generally those who have some combination of superb skating ability, strength on the puck, and the acumen to move the puck effectively and quickly. In some situations, they will have to deke and skate by an opposition player or two, and in other situations, they'll have to make a quick pass past pressure, up to a forward and out of the zone.

In the NHL, these types of players are names like Cale Makar, Devon Toews, Adam Fox, and none other than Michigan's own Quinn Hughes. While Makar, Toews, and Hughes are all world-class skaters, Fox is not, as he relies on deceptive moves with the puck to open up passing lanes to then get it out of the zone. Here are some clips that Jack Han assembled of Makar, Toews, and fellow Avalanche defenseman Samuel Girard, all of whom are great skaters, who excel on zone exits. These clips are just a loop of them retrieving the puck, wiggling around the first forechecker, and then making the pass up ice to jump start the rest of the transition game (which we'll talk about shortly):

In this two minute reel we see a lot of the same high-level zone exits being made. The defensemen get to the puck, they see the opposition right around them, and then they make a quick decision on what the best way to get it out is. Sometimes it's skating it out themselves, other times it's an immediate pass to a forward who then gets it out, or sometimes it's skating up with the puck a bit before making a stretch pass to a forward in the neutral zone. No matter the particular instance, being able to combine skating and passing ability with a brain that can problem solve on the fly is the best way to ensure clean zone exits and to begin the next phase of the transition game.

Cam York was a good puck-mover who was strong at regroups [James Coller]

Regroups

Once you get out of the defensive zone, it's time to start moving with the puck through the neutral zone. A regroup is when a team attempts to move through the neutral zone while penetrating the opposition's forecheck. Our next post will talk more about forechecks, but they are essentially set alignments meant to stop the opponent from advancing up the ice. Thus, there has to be a strategy on how to get through the teeth of a forecheck, and that's where a regroup comes into play. Again, this is where having puck-moving defensemen become very important, as most regroups hinge on the defense making a pass up the ice to a forward, who will then try and weave past opponents into the offensive zone (the zone entry).

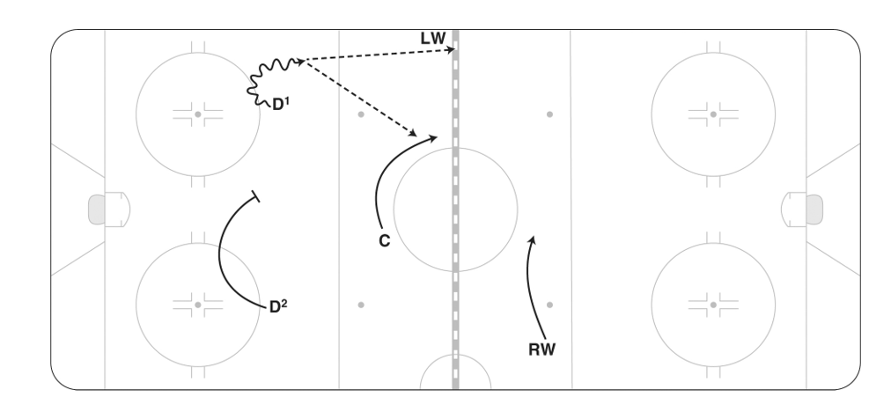

The most common kind of regroup used in the NHL is the "quick up" regroup, in which a defenseman simply makes a quick pass up the ice to the forwards to jump start the offense moving forward. The ultimate goal is that if executed quick enough, it doesn't give the opposition time to react. Here's a quick diagram of what a quick up regroup looks like, via Hockey Plays and Strategies (2018):

And here it is in game action form:

The whole of this video blends regroups and counters but the first clip, from the outset to the five second mark, is what we're looking for. The defenseman for St. Louis Torey Krug (STL47), gets the puck right at the blue line, and seeing how Colorado has set up their forecheck, makes a quick pass up the wing to his right wing Vladimir Tarasenko (STL91), who is then in great position to enter the zone.

Regroups all largely have the same premise, with a defenseman passing up to a forward, who then initiates the zone entry. Some have passing between defense partners, or more skating before the pass, but they all mostly boil down to this same idea. You may notice that in the diagram and in the clip, the puck hasn't actually exited the zone before the pass is made. That's because all these plays, the exit, the regroup/counter, and then the entry all link together. The last part of the zone exit is simultaneously the first part of the regroup, and the last part of the regroup is also the first part of the zone entry. Once the pass on the regroup is made and the forwards have the puck, it is their job to get it into the zone.

Counters

Before we talk about zone entries, though, we have to do a quick interlude on counters. Counters occur when the offense is trying to move up the ice but is not attempting to slice through an opposing forecheck. Most of the time this refers to situations where the opposition has gone for a change and there is a quick pass made up the ice, intent on catching the opponent off guard and not set in their neutral zone forecheck. These possession counters are seen quite frequently over the course of a season. Here's one such example from this year between the Hurricanes and Stars:

Pretty simple. The Stars are off for a line change, the defenseman Brett Pesce sees the situation and pounces, executing a quick pass up to his forwards, who then get an unobstructed breakaway chance as a result of Dallas' sloppiness. That's one instance of a counter. You may have noticed the announcer saying the words "quick up" during that clip to describe the pass made by Pesce, and indeed the concept is mostly the same as a quick up regroup: a quick D -> F pass up the ice. It's just the nature of the situations that makes it different, as again, a regroup moves through a set forecheck, a counter does not. In this situation, the opposition is not set up, so it's a counter.

Both the counter and the regroup show the importance of having defensemen who can move the puck, and why coaches try and have at least one defenseman who is comfortable passing on each defensive pair. Though the name "defenseman" would lead you to believe that simply stopping the opponent from scoring is the main responsibility of the position, there's really a lot more to it, and being able to pass is a crucial skill. A defenseman who struggles to pass the puck up the ice is one who has a limited range of abilities, and it's why having a Quinn Hughes or Zach Werenski is such a game-changer: a defenseman who can skate the puck out of his own zone and then make effective passes up the ice to forwards are the single greatest key to having a successful transition game, in your author's opinion. Stopping the opponent from scoring is only half of the puzzle for a defenseman; getting the puck out of the zone and up to the forwards is the other half. Some defensemen, like Michigan's Keaton Pehrson, are quite good at the former but struggle with the latter, and thus are considered liabilities. Other defensemen, like Tyson Barrie of the NHL's Edmonton Oilers, are good at the latter but struggle with the former. Those who can do both at a high level, the Cale Makars and Adam Foxs, are the elite defensemen.

Matty Beniers' excellence on zone entries is a reason why he will be a high NHL pick [James Coller]

Zone Entries

Once we've gotten the puck out of our own end, and passed through from the defense to the forwards through the neutral zone, it's time to penetrate the offensive zone via what's called a zone entry. Zone entries at even strength, unlike zone exits, normally fall on the shoulders of the forwards. This should be rather logical if you've been following along to this point in the article, as the end result of both regroups and counters is that the forwards have the puck. Like zone exits, there is a controlled and uncontrolled type of zone entries.

The uncontrolled zone entry is called a dump in and teams that build their offensive system around uncontrolled entries are said to be playing dump and chase. The play is exactly as it sounds, one player shoots the puck deep into the offensive zone and the other forwards chase after it, with the intent of retrieving it, gaining possession, and then beginning an offensive possession in the OZ. Here's an example of an uncontrolled zone entry working successfully:

Another rather simplistic goal. The puck is dumped in by the Lightning, Tyler Johnson races in and snags it, and makes a quick pass to Pat Maroon in front for a tap-in goal that the goaltender has a limited chance of saving. That's uncontrolled zone entries working to perfection but a lot of times it doesn't go like that. In general, uncontrolled zone entries, and playing dump and chase overall, is a pretty inefficient approach to offense. You need to have the forecheckers to make it work, good puck retrievers who combine speed and strength. Johnson in the above clip has the speed to win races but not every team is going to have that kind of player. Not to mention the potential strengths of the opposition: what if the opponent has defensemen who are proficient at zone exits of the kind we talked about at the start of this article? Remember, the plays that for the offense are zone entries, can also be the defense's zone exit.

It's worth noting that in college hockey, the absence of the trapezoid makes playing dump and chase even harder, because a good puck-handling goalie (like say, Michigan's Erik Portillo) can come out to play the puck to a defenseman to begin a zone exit the other way before the forwards arrive to retrieve it. Most commonly what happens when you play dump and chase, though, is neither a clean puck retrieval and a high danger chance like the above clip nor a crisp zone exit by the defense. Instead, dump ins tend to result in long grinding sequences of forechecking and board battles before either a meek shot or a defensive retrieval and an exit much later. Why are long sequences in the OZ a big deal? Well, hockey researchers have found that empirically, the longer an offensive possession goes on (measured in time since the zone entry), the less likely the offense is to get to a high-danger area and get a quality scoring chance.

So the goal should be to get a chance quickly after entering the zone, and the best way to do that is to enter the zone with possession. Ideally, just like how every team should have one defenseman who is comfortable handling the lion's share of zone exits, they should also have one player who is comfortable as a puck carrier enough to shoulder significant weight on zone entries. In the current NHL, one player stands roughly 30,567 miles ahead (not scientific data) of every other forward when it comes to generating successful zone entries, and he also happens to be the best player in the world: Connor McDavid. McDavid's ability to skate at a high rate of speed, yet still be strong on the puck while moving that quickly AND make lightning quick decisions at that speed, is unparalleled in hockey history and it's precisely that combination of skills that make him a Walking Zone Entry. This following clip is from a power play situation (where zone entries are also important but a bit easier due to the numerical advantage on the ice) but it is the best display of skills that McDavid possesses that makes him so lethal on entries:

There is no other human on planet Earth who can make that play. But it shows what I'm trying to hammer home, a player who is fast, strong on the puck, and has great hands to wiggle by defenders. That skillset is one of a kind, but players who can replicate even just mere parts of that are extremely effective players on entries. One of Michigan's current top zone entry players is Matty Beniers, and he's able to excel at entries because he has above-average speed (at the NCAA level) and is pretty strong on the puck, allowing him to weave through the defenders and enter the zone with possession. Here's a more mortal-looking example of what a successful, dynamic zone entry can look like from another terrific skater, Toronto's William Nylander:

A little deke on the fly, then the speed allows him to gain the zone and quickly generate a dangerous scoring opportunity. Though speed certainly is an important component of entries, we shouldn't mistake it to be the only thing that matters. Bigger and slower players can also be strong entry players because of their strength, especially if the opponent is utilizing an active neutral zone trap to try and bog down the entry and force a dump-in. In those situations, it may be easier to bully the puck into the zone with brute force rather than trying to skate through 3-4 bodies.

So there really isn't one path to being great at zone entries. Players with different skillsets can achieve an entry all the same if they curate their talents for the task. Some get there with speed, others with strength, but regardless, the importance of the controlled zone entry is the same. Teams who are consistently able to enter the offensive zone with possession will generate a higher volume of quality offensive chances, and therefore, more goals.

What about odd man rushes?

Odd man rushes (OMR's) are another component of the transition game that hasn't been discussed yet. Like all of these other aspects of the game, teams practice OMR situations, be it 3 on 2's or 2 on 1's. However, OMR's rarely result from set plays. Typically they arise due to a certain development on the ice. For example, the opposition is pressing for a goal, three players are caught deep in the offense zone, the defense digs the puck out and starts to skate up the wall, the opposing defenseman pinches to hold the puck in, but a forward pries it past him and suddenly it's a 2-on-1 going the other way. Want to see that play I just described in real life? Here it is:

Most OMR's result from the offense getting over-extended in the offensive zone when the puck is turned over, creating a numerical advantage for the team who has just gained possession. Other times, though, they can result as derivatives of the plays we have previously discussed in this piece. As we noted, the point of a counter is to catch the other team off guard, and as the example I used in that section shows, breakaways or 2v1's are often the result of a successful counter. Another instance is an OMR off a regroup. Once the defenseman makes the first pass up the ice to the forwards, he may choose to follow his pass and jump up on the play, which can create mini 3v2's and 4v3's coming through the neutral zone and into the OZ upon entry. Here's an example of that kind of play:

Here you have Alec Martinez (VGK23) make the first pass out of his zone up to Chandler Stephenson (VGK20) at center ice, but watch how as soon as Martinez makes his pass, he follows it up the ice and starts racing down the left-wing boards. He wins the footrace with Kevin Fiala (MIN22) who trails off covering him, and suddenly it's a 3v2 as Vegas enters the offensive zone, and the Knights quickly strike and score a goal. Having good skating defensemen who can follow their passes up the ice in a hurry and create those mini-OMR's are a way to manufacture offense and repeatedly generate high-danger chances. Some teams, like this year's Florida Panthers team, built their whole offense around having slick skating defensemen who aggressively rush the puck and race up ice to create changes like that.

Creating and finishing OMR chances is the result of having both solid skaters, and players who have the tools to make skilled offensive plays while skating at a high rate of speed. Some players, like Michigan's Luke Morgan, have the speed to generate OMR's for himself and his teammates at the NCAA level, but lack the toolkit to score on many of those chances. Detroit's long time forward Darren Helm is a similar way. Other players have the skill to finish those chances but may lack the speed or the processing time to use those skills on the fly. That was something that Michigan's Kent Johnson struggled with last season. So the best OMR players are those who can skate fast and use their toolkit while on the move. In my opinion, Johnny Beecher, Thomas Bordeleau, and Matty Beniers were the best at it last season on Michigan's team.

Owen Power will shoulder a big transition load in 2021-22 if he returns [JD Scott]

Conclusion: What have we learned?

Here I'm going to quickly run through in bullet fashion what I think are the central takeaways from this piece, in case readers want a TL;DR style recap of what was discussed:

- Transition play is how hockey teams turn offense into defense, and it consists of several interconnected sequences, the zone exit, the regroup or counter, and then the zone entry

- Zone exits are largely the responsibility of the defensemen and are accomplished either in controlled or uncontrolled fashion. A controlled exit is preferable and accomplished by skating the puck out or making a first pass to get it out, while an uncontrolled exit occurs when the puck is flipped out of the zone and down the ice

- Regroups are set plays meant to move through the opposition's neutral zone forecheck, and normally consist of a "quick up" play where the defenseman hits a forward in stride with a pass to trigger the zone entry

- Counters are plays that happen more spontaneously and are meant to move through the neutral zone when the opposition's forecheck is not set up, typically when there is a line change going on

- Zone entries can also be either uncontrolled or controlled. An uncontrolled entry is also called a "dump in" where the puck is shot into the zone and retrieved, while a controlled entry involves a puck-carrier skating it or passing it into the zone. Controlled entries are vastly preferable to uncontrolled because they result in more dangerous chances.

- Having one defenseman who can handle a high volume of exits and one forward who can handle a high volume of entries is vital to being a successful transition team. Ideally both players would have good vision/passing ability and be strong skaters

- Odd man rushes happen in a variety of mostly naturally occurring circumstances and require quick and skilled players to regularly capitalize on them.

Some really, really good stuff here - thanks for writing. I would like to add that there are a couple important points that you may have omitted a bit.

1. While controlled exits and entries are preferred, you seem to be assuming that they always work as intended. There is no more dangerous time for a turnover to happen than losing the puck on a failed exit or entry. While uncontrolled exits and entries certainly lead to less offense, they are safer plays and generally improve your defensive outcomes. (This is why teams holding a lead tend to use both). The worst place on the ice for a turnover is at either blue line.

2. There also seems to be an assumption that the opposition has no say in what works and what doesn't - or perhaps I didn't see your emphasis. Many teams predicate themselves on forcing you to do dump and chase hockey (1990s NJ Devils most prominently). Teams that loved puck possession (like the Red Wings) had a lot of trouble with those trapping teams. When the more puck possession teams are forced to try dump and chase they are largely rendered useless as they have the wrong players for that style and they lose. An interesting part of hockey is when one team tried to impose their style on the other in this fashion. We see it in basketball most often when one team tries to make the other get out and run and the other walks it up the floor. Hockey has something similar in which team can force the other to play their style.

3. Minor point: an uncontrolled exit isn't really like sacking the quarterback. It's more akin to gaining possession of the football after a goal line stand at your own 3 yard line. Then, you punt on 1st down. You gain the desired field possession, but you go right back on defense right away.

Great stuff. Thanks for writing it.

Was going to say something similar to your points 1 and 3. With regards to dumping and football analogies. A dump is like a punt, where maybe the analytics say you should pretty much always go for it on 4th down, but teams and coaches still choose to punt because its conservative and it rarely burns you. Same thing with a dump, analytics say don't do it, but everyone does because its very low risk and you then force the other team to go through your defense to score.

If you abolish dump and chase from your playbook its like refusing to punt no matter what, when it doesn't work its going to blow up in your face big time.

Yeah I think you’re referring to clearing your own zone. I’m talking about playing dump and chase as an offensive strategy. The article makes it sound like no one sane would ever try to dump and chase. But effectively every team does it.

Why is losing the puck around the blue line so dangerous? Also, how do icing and offsides penalties affect changing zones? I don't even know what those penalties do to be honest.

Alex can probably explain more eloquently, but when you turn over the puck at your own blue line, that’s obvious that now the offense has a good opportunity where they want to be, when you turn it over on the opposing blue line, that’s a little harder to understand why it’s a big problem, but it leads to counter attacks, basically your whole team is advancing towards the offensive zone while the opponent is retreating, then you turn it over and that situation is reversed. Now the opponent is attacking and you team needs to get back to defense. This is when people get caught “flat footed” and the opponent gets an odd man rush. Why does the blue line create this opportunity more than other points on the ice? Basically because of off sides, you’re taught to get the puck in because all your teammates are anticipating that you do so, to avoid an offside whistle. So the other 4 guys are expecting the puck goes forward, then when it doesn’t your whole team has to scramble to adjust. The opponents blue line is kind of this mental and literal dividing line in the ice.

Icing is when the puck goes from your half (the center red line) to behind the opponent’s net. It affects clearing the zone cause your can’t just fire it as hard as possible down the ice otherwise you get an icing call. That just means the face off comes back to your own zone AND you can’t change who’s on the ice.

Offsides just means the puck has to cross the offensive blue line before any player does, otherwise the ref stops play. For the offense, it stops you from cherry picking. For the defense it just means that if you can get the puck 1 inch past the blue line, all the offensive players have to leave the zone and “tag up” in the neutral zone before they can re enter the offensive zone.

To your point 2, the NJ Devils employed what has been termed the "Left wing trap," which I don't understand. What is it? Why wouldn't it work on the right wing? Is that what ND uses to turn an exciting hockey game into soccer played in a swamp?

Thanks for the kind words! A few thoughts:

1.) Yeah, I suppose that's a fair point. I've intended this series to be more aspirational hockey than always realistic. The goal of every team should be to exit the zone with control every time, if possible. But there are many reasons why that might not happen, be it personnel, situation, etc. Some teams have 0 defensemen that can effectively exit the zone with possession on a consistent basis (hello, 2021 Red Wings) and are left having to dump it out all the time. I think part of this is stylistic preference when it comes to considering the concept of risk. You seem to be discussing a rather risk-averse style of playing and I would argue that while yes, DZTO's on a zone exit are extremely dangerous, the offensive benefits if you have a few guys who are proficient at them, outweigh the negatives. But again, it's situational, too. You're gonna ask Quinn Hughes to aim for most exits to be controlled. You'd probably be content letting Keaton Pehrson dump it out 9 times out of 10.

2.) Well, sure. Games are shaped by the way the two teams like to play, no different from any other sport. And you can be forced to do something you're not used to if the opposition is really good at one style play. But you should still have one mode of playing and I suggest that possession based teams who are focused on exiting and entering the zone with possession are the most successful teams... even those who play conservative trapping styles (like this year's Isles) still have players who are able to regularly generate controlled entries (Mat Barzal, for example). That said, the ability to play dump and chase needs to be always be in the playbook, even if it's not your preferred way of playing. Every team should have a way they want to play- but the Lightning winning B2B Cups shows how versatility is really important. Tampa can boatrace you and win a game 5-4, and they can also pack it in and beat you 1-0.

3.) Sure, I accept that metaphor, but that takes a lot more explaining so it's probably not fit for this kind of piece lol

I recall screaming at my television during the 1995 Finals for the Wings to dump the puck, but they continued to try to skate or pass the puck through the neutral zone. Turnovers led to odd man rushes, which led to go-ahead goals, which led to the Devils entrenching themselves even deeper into their neutral zone trap. It was infuriating. When the Wings were able to gain entry into the offensive zone, they had to contend with Marty Brodeur. I remember my favorite player, Vladimir Konstantinov, in tears as the seconds counted down in game 4 as the Wings were swept. I learned to hate trap-style hockey that year.

I'll add a couple things here as well. This is more just general for new hockey fans.

1. You use the term "plays" but it's important to note for new fans that these aren't really set "plays" like you would think of being run in football or basketball. There are general concepts like cycling, but no coach is calling "red six" and now everyone knows they're going to cycle 3 times in the right corner then have the left defenseman cut in for the pass from the corner. Seems obvious but I've seen new fans get confused.

2. I know this is a really basic breakdown, but dump and chase isn't just "one forward dumps it, the other forwards chase." Teams have all sorts of different ways to forecheck after the dump in. 2 low/1 high, 1 low/2 high, 1 low/1 front/1 high, 1 low/2 wings, etc.

this is probably the best hockey assessment/breakdown i've ever seen.

good stuff

Thanks. This is very helpful for us casual hockey fans.

Excellent work!

Great stuff. Now I have to commit to getting the rest of my Beer League team to read this.

MSU under Ron Mason played a lot of Neutral Zone trap.

And maybe not quite as good as Connor McDavid, but I've seen some very pretty end to end rushes from Mike Comrie and Mike Cammelleri when they wore the maize and blue.

Awesome article. Thanks for writing this. After watching the Stanley cup playoffs, I really came to appreciate the game and want to learn more. If anyone knows other good website to read and learn, I’d greatly appreciate it!

Comments