What Is: Pin and Pull

This series is a work-in-progress glossary of football concepts we tend to talk about in these pages. Previously:

Offensive concepts: RPOs, high-low, snag, covered/ineligible receivers, Duo, zone vs gap blocking, zone stretch, split zone, inverted veer, reach block, kickout block, wham block, Y banana play, TRAIN

Defensive concepts: Contain & lane integrity, force player, hybrid space player, no YOU’RE a 3-4!, scrape exchange, Tampa 2, Saban-style pattern-matching, match quarters, Dantonio’s quarters, Don Brown’s 4-DL packages and 3-DL packages, Bear

Special Teams: Spread punt vs NFL-style

----------------------------------

This segment has a sponsor! Reader/previous MGoSponsor Richard Hoeg noticed I’d made an offhand comment once about how this series doesn’t get a lot of responses and wanted to make sure we kept it around, so now he’s tying us contractually to it.

Richard recently left a lucrative career in big law to start his own firm, where he helps outfits like ours start, operate, fund, and expand their businesses. His small group has clients including a national pizza chain and a major video game publisher, plus an array of university professors, entrepreneurs, and licensees. Hit up hoeglaw.com or Rick himself at [email protected], or read his blog(!) Rules of the Game.

----------------------------------

The Play:

So this is a zone/power hybrid that Michigan ran last year instead of outside zone, and had it run consistently against us in the latter half of the season. We call it “Pin and Pull” but it also goes by “Packer Sweep” or “Double Power” or “Student Body Right.” It’s really old, and was all the rage at the top levels of football until the less extreme/simpler to install outside zone occupied most of its niche. But pin and pull is still popular, and made a comeback in recent years as power blocking came back in vogue and offensive coaches searched for a way to punish defenses for putting smaller coverage dudes around the edges of the box.

WHAT IS IT?

The concept seems simple enough: block down everyone you can, and pull everyone else around. Pin and pull. Based on the defensive front any guy on your line (and you want your line extended to tight ends and beyond for this) might be pulling, or blocking down, or executing a reach block or combo block.

Ideally, you’re getting all of those dangerous DL blocked with your own heavy OL and TEs from advantageous positions, then swinging more meat to the point of attack to meet the smaller defenders—cornerbacks, safeties, OLBs, hybrids, etc.—who hang out there. From there it’s a matter of your back reading his blocks, and physics.

Given Michigan’s TE-heavy roster and power run orientation this looks to be a bigger part of our own future—right now it’s the basis of those sweeps we pull out from time to time. We’ll also see it a lot on defense, since even without Peppers Don Brown is often going to leave an open invitation to try it.

[Hit the jump to see how it’s run, and how it’s beat.]

----------------------------------

HOW DOES IT WORK?

Learn from the greatest

Like outside zone, a pin and pull play changes up the blocking based on the front, but those calls get way more complicated, especially today when all sorts of zone blocks are also incorporated.

Typically teams that run this will try to stack lots of bodies to that playside. The Packers used to run out of splitbacks, but the modern H-back serves the same purpose as Green Bay’s old fullback, except the H starts in a better position to make his block (Lombardi used to tell that guy to cheat up toward the line when he could), and can use motion to get the defense out of alignment and create better matchups.

The key block is usually going to be that last Tight End versus the end man on the line of scrimmage. Running this play to punish an EMLOS who sets up inside all the time is one thing but once you’re making it a big part of your offense, you’ll need a way to deal with an edge man setting up too far outside to routinely cave. Lombardi had our ol’ 87, Ron Kramer, a nasty blocker who was enough of a receiving threat to require a leaner defender to guard him. Lombardi would split Kramer up to 3 yards away from the tackle in order to create two running lanes either side. The pullers would then pick whichever side of that block Kramer won, and the back would follow. In the top example when you see Butt motioning out to nearly the slot, that’s what’s going on. This is the zone part of the play coming through: you’re trying to outflank the defense, but if they’re not having it there should be multiple options to cut inside.

The blocking assignments are where it gets so complicated it’s probably best if we stay out of the minutiae. Every coach who runs it is likely to tweak the blocking based on his personnel, what they’re normally good at, and gawd all sorts of things. For example if a TE and OT are great at combos, the coach might have them do that like an outside zone:

Or if they’ve got a reach blocking maniac like David Molk at center, or the opponent’s nose tackle is slow or has been regularly attacking a backside gap he’s not lined up in, you can win easier blocks elsewhere by asking the center to reach. Teams also can screw with how they block the cornerback, either by having the receiver lined up over him handle it, or using up a blocker from the inside to kick the corner while his receiver is cracking down on an inside defender.

In general, like zone you block a guy lined up over you, even if he’s on your playside shoulder. That might seem counterintuitive—why not have your buddy block down while you pull? If he can be trusted that can happen. But teams running this will often align with wider splits (to make sure your tight end can flank the last defender), so if you don’t do something to stop a lineman lined up over you he could shoot into the backfield before anyone else can get to him. If you’re clear, you pull. Some examples:

If those blocks go well, and the pullers didn’t all run into each other in the backfield, the offense has won itself a massive mass advantage at the point of attack. Often one of the pullers will find a cornerback or safety setting up on the edge, i.e. a 180-pound dude standing still is about to meet a 300 pound man with momentum.

----------------------------------

LET’S SEE IT

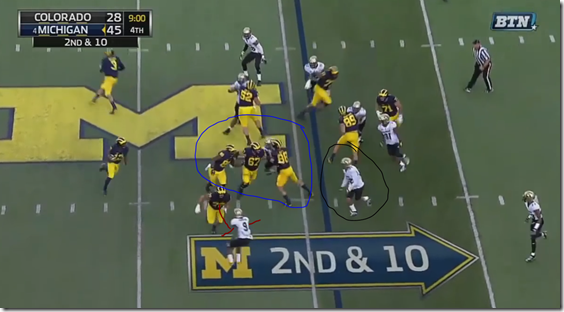

So here Michigan is salting the game away and comes out with (for them) a very wide split. Butt, the H-back starts going in motion, first like an offset fullback…

…and then going out really far wide of Bunting, and almost on the line of scrimmage. Why? Because remember this is a flanking maneuver.

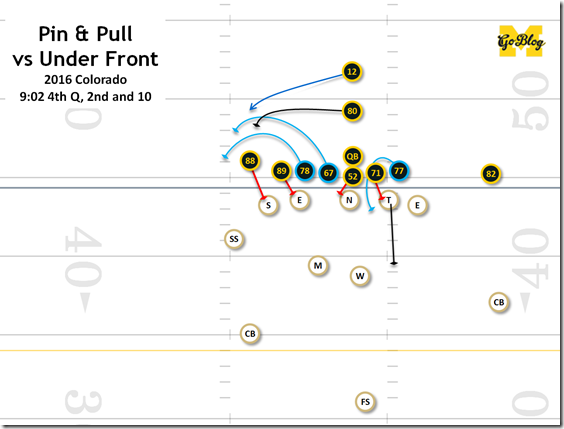

pin=red, pull=aqua

Let’s look at the alignment and try to figure out the blocking assignments. Cole has a nose tackle lined up on his playside shoulder, but can decide that this is fine—Cole thinks he can reach that NT, which means Kalis, lined up further playside, can be the puller. Come the pitch that all looks like it’s going swimmingly:

Normally you get a cornerback but the Buffalo player on the bottom of the screen coming up the hashes to be the force player is a safety, 2017 Seahawks draft pick Tedric Thompson. But even a 200-pound safety would have a hard time holding the edge if he’s plowed into by an OT, and sure enough Magnuson gets a good kick. This ought to leave another puller, the fullback lead blocker, and the ballcarrier against whatever linebackers managed to pick their way into the gap and perhaps the cornerback (Ahkello Witherspoon) who swapped jobs with Thompson.

Of those only the Mike linebacker seems to have arrived.

However Butt’s block on the Sam linebacker went badly—like 3 yards in the backfield and not sealed badly. Lombardi’s rule is you can let that guy upfield but never inside—Harbaugh’s plan is pin him inside with the rest. Either would work, but this doesn’t. It jams up the lead blockers so that Kalis and Hill are just in each others’ way.

That linebacker would dive past Kalis at Hill’s knees, taking out both blockers and even getting into Evans’s knees.

Evans managed to stay upright and the detritus delayed the Will some, so Evans can scamper to the sideline for a 4-yard gain before Witherspoon (bottom-right) can knock him OOB.

----------------------------------

QUESTIONS:

Why do teams that run this choose to reach block (hard) instead of block down (easy) when a DT is lined up on that playside shoulder?

They don’t always but as a general rule you never want to leave a free path to the backfield. Especially for Mo Hurst. At least a reach block attempt is likely to end in some sort of stalemate long enough for the ball to get outside. Remember it doesn’t have to turn into a complete seal, just get enough of that DL to prevent him from flowing down the line before the play gets by him.

Remember you’re trying to outflank here, and your cavalry are offensive linemen trying to beat their linebackers to the edge. The more material you can pull from the frontside the faster it will be in position.

Why did Michigan see this 4 times a game last year even though it was constantly blown up? This goes back to why Peppers was a legit Heisman candidate in the eyes of all the smart football guys and the Cleveland Browns. Michigan’s regular alignment is asking for this.

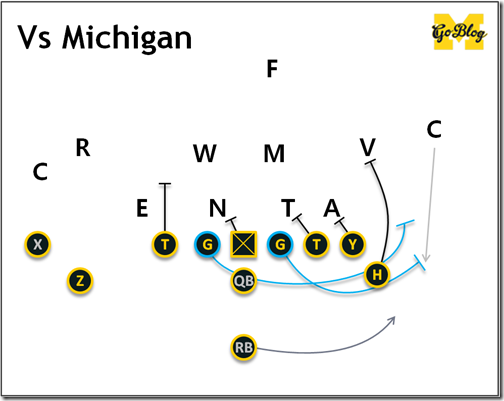

Don Brown’s over front regularly slid the tackles and Anchor (Wormley/Gary) inside, providing offensive players a better angle to block down if running outside. The safeties would rotate with motion so if you sent your Z receiver jetting to the other side Michigan would flip matchups and leave a cornerback (often Stribling, whose run defense was suspect) as the overhang. And just to entice further, Peppers (V for Viper above) would set up at the edge of the box—like a safety—rather than setting up in the H-back’s grill like a linebacker.

All of that made Michigan’s defense really hard to run inside against. So teams meant to punish that tendency with this consummate outside play that tested how often those edge defenders could win from an disadvantageous position. What they got was, at best, a linebacker versus running back matchup they liked; as often they got this in the face.

I’m sorry, were you running to that hash?

It didn’t have to be Peppers, whose job was to spring up and set the edge, but didn’t have the weight to stand up to a guard or tackle out there for longer than it takes to force the play back inside. Michigan would also destroy this when Wormley or Gary would dominate those TEs trying to downblock. Delano Hill might shoot up from his safety position before the pullers could get out of the backfield. Even when Michigan was slanting away from the playside (usually a death knell) Gedeon had the speed and reflexes from his middle linebacker position to chase it down.

And note in the diagram I had the frontside tackle downblocking the DT while the guard pulled, even though the 3-tech was shaded over the guard, because it wasn’t likely Godin or Hurst would get reached. But downblocking from so far away had its own disadvantages, especially against Hurst.

How hard is this play to learn? It’s one of the more difficult plays to get right, but it’s also quite rewarding to a team that knows all the ins and outs, and can run it against any front and any opponent. Those teams rarely exist today, so for the moment Lombardi’s base is mostly a changeup that power running teams use to break tendencies.

Theoretically there’s room for a pin and pull based offense in modern football. However it does come with an ancillary downside that most coaches know about: defensive backs will regularly chop down your pulling linemen at the knees in order to win back those behemoth vs little guy matchups. Newsome’s injury came on one such play. It should be outlawed, and if they ever do make that rule you might see a Packers Sweep team again. For now, making this something your opponents prepare for is just a good way to lose linemen.

----------------------------------

DEFENDING IT

Again my theory on defense is you can beat any play by playing sound football, by running something otherwise unsound to stop it, or with a fantastic individual effort.

Option A: Read your keys/execute your assignment

Execute your assignment and James Franklin is bound to screw up.

Pulling guards are a key though far too often linebackers will read the backfield, setting themselves up to be caught out of position on counters and play-action. Watch McCray reading the tackle pull and setting up outside where the OT’s cut attempt just ends at McCray’s knees. See how everyone stays in their lanes, even when scary running back Saquon Barkley breaks loose in the backfield and reverses field. The backside defenders made this play by keeping discipline throughout.

Taco also dominated that TE, playing both sides of the block to hold Barkley up from making a decision on which side of the block to try. That TE is Mike Gesicki, i.e. a guy whose blocking makes Funchess’s look like the guy whose number he was wearing at the time. Franklin put his player in a position to fail, and Michigan was able to take advantage without doing anything unsound.

Option B: Solve your problem with aggression

In Soviet defense EMLOS blocks down on you!

So remember how Michigan’s defense sees this play a lot because of a tendency to line the Anchor up shaded inside a tight end? Changing that tendency then can change things quite a bit. This is a passing down where Michigan presents an Okie front expecting to pass rush. Wormley sets up outside all of the tight ends and now he’s the guy hammering in from an advantageous position.

Getting into the outside TE so far in the backfield creates an immediate jam where the play is supposed to go, and now all of those DBs who were supposed to get pullers in their faces are free to converge. Wormley got a 4-for-1!

Option C: Kick Ass. I already showed a bunch of examples in the Q&A portion for how a great player can shut this play down. How much more blood would’st thou have needlessly spill’t to slake thine thirst for…oh fine have it your way:

Getting out-hit

----------------------------------

FURTHER READING: X&O Labs on concept blocking and TE blocking. All22Chalk on how the Browns run it vs an odd front. Stuffing OSU’s version with a Bear front. Coach McKee’s youtube series on a run-pass-option version of it. Our pitch sweep tag.

Our D-Line absolutely destroys their offense in that last gif

I'd forgotten about that! I'm adding a caption for it.

Probably need a NSFW tag on that and the Peppers play against Hawaii, too.

Why, on that play Gary got out-hit by no less than three Knights en route to smothering the ball carrier like an angry, depleted uranium quilt.

This is the returning starting D-line for this year minus one Glasgow. I'll grant you it's a pretty big minus, but still our starting D-line should be ok guys.

Michigan defense two years ago when Indiana repeatedly used pin and pull block on them when Jordan Howard ran all over them.

Indiana used Pin and Pull to great effect against Michigan defense and it helps that Jordan Howard had patience, burst and vision to pick lanes. They ran a ton of IZ, not OZ.

The db chopping o linemen should not be outlawed.

reasons?

Health of the players (NOT!)

Because that's the only way Romeo could force a team to punt back in 2002.

Too many things can go wrong and they all seem to have to go right for the play to work. I'd much rather run plays that only rely on one or two proper reads from a couple players to get the play to work.

Awesome writeup though. Thanks Seth. These play analyses rock.

I first heard of pin and pull from Brian doing desultory DeBord-era UFRs, but it is interesting to see what happens when it's run well and the opponents don't know it's coming.

Good stuff, as always, Ace. I really enjoy reading these. One of the many things that separates mgoblog from other football blogs. I actually get to learn some football concepts.

Is this similar to the pull and pray method? Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn't!

There is a neat passage in Tim Layden's Blood, Sweat & Chalk about former Michigan Wolverine Ron Kramer, who was the TE (responsible for sealing the EMLOS) on Lombardi's great Packer teams. Apparently Vince Lombardi said Kramer's blocking was the reason the Packers' sweep play did so well, and Kramer teared up when he heard that.

There's just so much between the two now I don't know where to draw the line. Especially once I watched how Lombardi himself ran it I found there is no difference, because he was doing all of it depending on all the tiny variations of fronts they saw. Yeah zone teams might zone more and power teams might lean toward more downblocks, but I think that's a game by game and matchup by matchup and play by play designation more than the type of team that's running it. The center pretty much gets to look at the nose's alignment and decide what block he can execute on that guy. Like coaches, players develop tendencies, so I agree you'll see some consistency in how one team runs it. But I thoughtr about this a lot and decided they're the same play when called, therefore they're the same play.

Yeah I totally get where you're coming from. The only deviation is man, did you see how much zone blocking the Packers were doing on their base sweep? For the readers though I didn't want to draw too big of a line because it's impossible to tell from the stands. Just like we can't tell after the fact whether a Don Brown stunt was called pre-snap or if it was a stunt option based on a high-/low-hat read.

"swinging more meat to the point of attack"

heh. That's my strategy.

I love reading these. There is something I learn each time I read one of these. Thanks Seth.

Thank you for these write-ups. Knowing somewhat what teams are trying to do helps me enjoy football even more. I enjoyed the Lombardi teaching video link also, although it was somewhat like a middle schooler showing up in a calculus class for a day.

Seth -- please continue these....

Also, I would just say that this is conceptually like to throwing a Screen pass into the right flat, but instead crossing up the D by running on a (sort of) passing down.

In the Colorado GIF example, their Middle linebacker (#30-something) does a nice job to read the play, defeat two blockers and roll into Evans' feet. Doesn't make a tackle, but prevents a longer gain.

Yeah I was really impressed by that guy, whom we didn't think much of in the preview. But he got the opportunity because Kalis was held up by Butt's block going poorly. I had literally one hundred (row 101 of my spreadsheet listing them) of examples to choose from for this one since so many teams run it and Michigan liked it too, and chose the Colorado example becauser that key block Butt is making can make or break the whole thing.

At the end of the Evans run, the announcer says, "You can't do that." Do you know what he's referring to?

Comments