Neck Sharpies: What Is Playing to Spill

This series is a work-in-progress glossary of football concepts we tend to talk about in these pages. Previously:

Offensive concepts: RPOs, high-low, snag, mesh, covered/ineligible receivers, Duo, zone vs gap blocking, zone stretch, split zone, pin and pull, counter trey, inverted veer, reach block, kickout block, wham block, Y banana play, TRAIN, the run & shoot

Defensive concepts: The 3-3-5, Contain & lane integrity, force player, hybrid space player, no YOU’RE a 3-4!, scrape exchange, Tampa 2, Saban-style pattern-matching, match quarters, Dantonio’s quarters, Don Brown’s 4-DL packages and 3-DL packages, Bear

Special Teams: Spread punt vs NFL-style

We've been throwing around a term for how Michigan is playing defense this year a lot lately and haven't stopped to explain what it means: Playing to Spill.

Definition

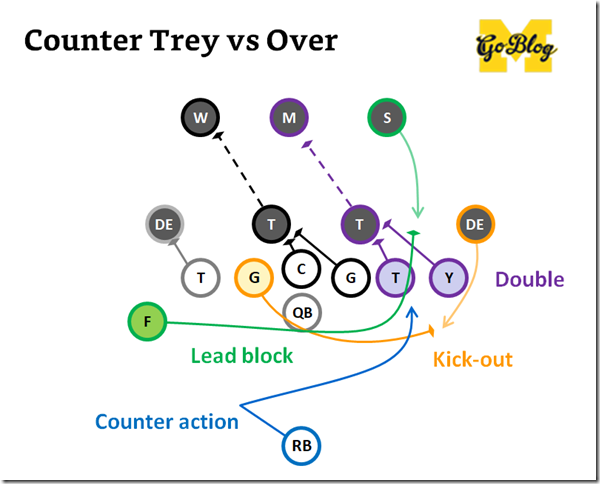

Playing to spill is a defensive technique where the force player (edge defender) dives inside of a kickout block while another defender pops outside. This is done on the fly, usually against power runs, as a way to screw up blocking assignments and force the ballcarrier into this now-unblocked outside defender.

A play

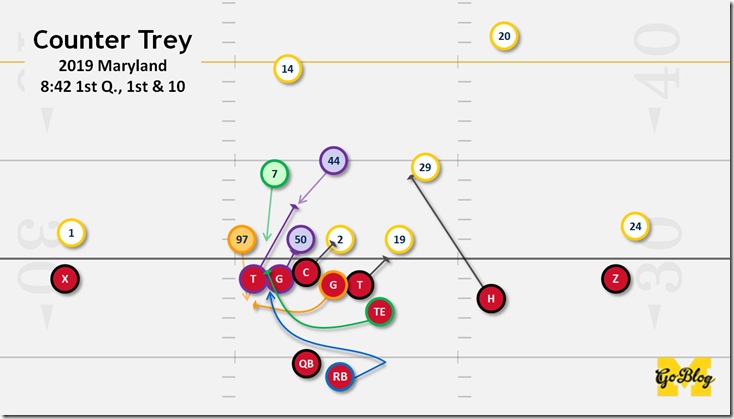

So Maryland—not for the reason you might think—runs an offense extremely similar to Michigan's. Particularly this week they were heavy into arc zone read and its counter, split zone, plus pin and pull and its flipside, Counter Trey. We've discussed Counter Trey on here a bunch. It's Pin & Pull the opposite direction with some counter action in the backfield to get the defense stepping to the frontside before you swing the ballcarrier and a few escorts to the backside.

Locksley's Terps will kindly demonstrate this for us:

This is vintage Locksley: trying to get you thinking about a run one way so you're not paying attention when it goes the other way, then he thunks your edge guy outside, pins you inside, and rips somebody's heart out. On this play you see the tight end come across the formation and the running back step that way like it's going to be that edge pitch Penn State liked to run, and it's a surprise when the ball goes the other direction. Michigan's defense wasn't fooled however.

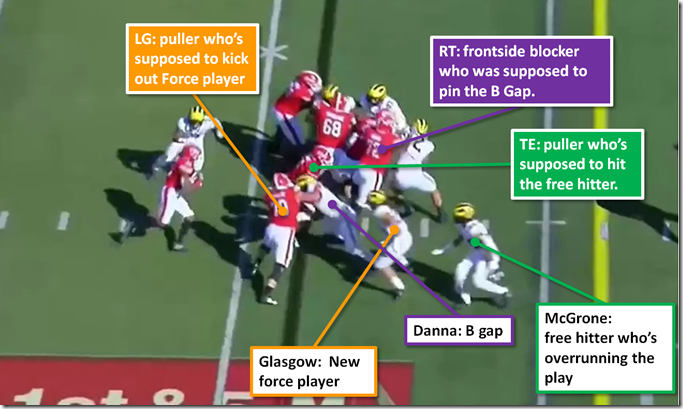

Remember, the pulling guard coming across the formation is trying to kick out Aiden Hutchinson, DE #97 on the top of the line. I want you to pay close attention to Aiden's response to the kickout. The pulling guard wants Aiden standing outside all passively. Aiden has other plans; he sees the guard coming…

…and leaps inside of him:

Aiden has now placed himself in the intended running lane. But this is Maryland's most base play, and the guard doing the kicking knows how to respond to this: turn the end inside. If you recall Michigan was doing the same thing on their pin & pulls versus Illinois.

The difference is here Michigan's defense has an edge.

[After THE JUMP: a scrape exchange for power]

----------------------------------------------

You probably already saw Khaleke Hudson, who wound up the WLB here thanks to the tight end movement, coming around to pick up the edge. Watch the exchange in the clip below. Aiden begins as the force player (edge dude) and Khaleke has a standard LB's B gap, which is the lane being attacked.

As with the scrape exchange, a defense that's playing to spill is going to have these guys swap gaps; the big difference is this is on the fly. Hutch is reacting to the crossing tight end, and Khaleke is reacting to what Hutchinson does to make him right. Here's a clearer example to the other side:

See where Mike Danna (#4) is lined up pre-snap. And see how he shuffles when nobody blocks him on the snap. That's a reaction, as is getting inside the puller. And then watch what happens with Glasgow, who took a step inside the hash mark, then quickly fixed his mistake and shot outside to get the edge. By swapping jobs, the defense survived the downblock of RT #72 (who can do nothing but double Carlo Kemp or go looking for a safety now) without getting their B gap player blocked, and won themselves an unblocked force player instead of a kicked one.

This is called playing to spill. Rather than let the offense have its gaps and hope everyone plays their part and wins their blocks, Michigan's defense has a quick check, and a check off that check, to force the ballcarrier to bounce, or "spill" over the side of the play. If somebody else arrives and tries to kick the new force player, he jumps inside, the next guy jumps outside, and so on until the sideline:

No matter how many players the offense brings to the edge, the defense should have numbers arriving until finally it's down the ballcarrier caught between an unblocked defender and the sideline. And you don't get credit for sideways yards.

Why do this?

Spill technique is often favored by teams with good, veteran linebackers and safeties, and not great defensive tackles. Note in the example video I began with, Mike Dwumfour got hammered inside by the Maryland guard's downblock. If you roll back to 2016 when we had a DT room filled with future pros it made sense to have Jabrill set the edge where he could and squeeze the ball back into the meatgrinder inside. Carlo Kemp and Mike Dwumfour are no Ryan Glasgow/Mo Hurst. So Don Brown protects them by adding more complication for guys like Glasgow, Hudson, and Metellus, and a bit more meat for the DE. If your DE is an especially meaty guy to begin with, you can dominate edge plays. Remember what Wormley used to do to tight ends?

Not only is he playing to spill, but raising the height of the glass.

Why not do this?

Like switching on cross routes, this adds a layer of complexity to your run fits. It's not "go to this gap" anymore but "go to this gap unless this guy does this thing." As any engineer will tell you, the more parts you add to a process, the more chances there are for something to go wrong. On the first play I clipped there's a moment where it looks like the spill has caused the RB to cut back into a gap with everybody in it:

Then suddenly Jevon Leake is squirting to the 37. That is because both McGrone and Metellus leapt outside of OT#71, the one free blocker for the three guys standing around waiting. That left the original B gap open again, at least until Metellus could leap back to the correct side of OT#71 and Glasgow could arrive from the back side to assist. #71 blocks nobody but it still gets 7 yards because of the screwup.

Playing to spill is counterintuitive, especially for a younger player, because of the danger, especially in high school ball, of letting a running back outside. Most coaches I know in high school run a 4-2-5 gap defense because it's way easier to teach high schoolers, many of whom are playing both ways, to just go to their gap, the last man setting an edge to compress the space for the runner. Playing to spill means getting yourself inside a blocker, trusting your next buddy to get outside and make the play instead of you. It takes time and trust to get used to ceding that to some safety who when last you met was backing out beyond the 1st down marker.

Not to mention how hard it is for the guy who jumped inside. Look what Kwity Paye ends up dealing with in this example:

You're starting outside the play, have to make sure you're not being read, spot the puller, cease the momentum of a 300-pound dude running right at you across the formation, get inside of him, and then hold up as everything your buddy forced back inside slams into you. This is a three-yard run and I think Kwity did about all he could (McGrone's false step with the RB dooms him to getting down blocked).

But the real disasters come when you have your edge guy switch to an inside guy and the guy who's supposed to replace him doesn't do so. Michigan had that happen earlier in the season, and yes you guessed the play:

Jordan Glasgow was new to WLB at this point and didn't flip with Kwity Paye when the latter jumped into the inside gap (also Josh Uche became the MLB when Ross blitzed and didn't react to the puller). If you're playing to spill your linebacker MUST replace when the DE in front of him goes inside, else you've got no edge. This happens to Illinois all the time. In this instance it turned a turnover-assisted bad start into a rout.

Attacking It

My theory of defense also applies to offense: you can beat any concept by playing sound football, by running something otherwise unsound that attacks that specific thing, or with a fantastic individual play.

Option A: Execute rock better

The defense is re-gapping here, so the offense needs to win back those gaps. One way to do that is to get in there and dig out the guy trying to re-gap. This can get dodgy in a hurry, but you weren't made a kickout guy for your lack of mass. And you don't need that block to last too long. I wouldn't be at all mad if this play was called a hold but it's technically not one: Eubanks had a hand on this guy's chest for the entirety of their brief contact.

Since the linebacker is already expecting the DE to spill, if you can still get that DE kicked there's nobody in the B gap anymore. The linebacker's job is to make the DE right, so it's on him for getting outside when the DE was still kickable. This is a spectrum; as much as this DE has shuffled down you can't really fault the linebacker for converting to spill technique. In less dramatic instances the DE will try to split the difference, and then it's incumbent on the kickout player to make sure there's a gap wide enough for the back to have a shot at putting the linebacker in the wrong gap.

Option B: Throw paper

The defense is switching jobs on the fly, so the offense can too. If these edge plays are your offense's bread and butter, you've practiced ways to zone block these defenders, often by swapping the two pullers' jobs when they arrive on the scene. That's some hard stuff to learn, but if you get it right you've just matched their blocks and you're back in business. It's subtle but watch Bredeson give Runyan a little tap here:

Bredeson noticed that Maryland's OLB/DE edge guy #5 was setting up inside and was going to be in a bad spot for Runyan—as the first blocker normally the kickout guy—to dig into. Runyan gets the message, and Bredeson lines up the edge guy. He didn't mean to be kicked, but now he's kicked.

The arc read play is another paper-ish response to this kind of behavior. You've got that DE thinking he's going to crash in and stop the kickout blocker from getting a crack inside of him, and then that kickout blocker runs right by and the DE is used up. Now that kickout guy has flanked the linebacker who's supposed to be replacing, and there's room to turn the corner.

Offenses also have play-action available to them. Maryland realized that Metellus was playing aggressively against the run, so they ran this PA action off their split zone look. Kwity steps inside as the TE lines him up, and then the TE (whoop!) is outside.

That's not a blocker anymore; it's the ball, and the linebacker supposed to be replacing Kwity by getting upfield and to the edge now has two bad steps upfield when he needs to be getting to this tight end.

You can also move the intended gap somewhere else. This was a hallmark of Harbaugh's power offenses: you'd have this great edge defense planned with your edge guys and then he'd have a formation with 7 linemen and three tight ends and any one of them could be the gap they're attacking. This is a much simplified Gattis version of such, where Michigan is attacking the A gap instead of the B. The DE may be schooled on diving inside, and the LB ready to make the DE right, but this isn't something the DT is ready for. Trap, thwack, yards.

Option C: Stab their rock with scissors because your scissors are made out of galvanized steel

To some degree the play in Option A by Eubanks goes here, but here's a better example from the forklift himself, BEN MASON. I recommend having the sound on.

That DE #4 for Nebraska didn't mean to be kicked. He shuffled as inside, and his linebacker buddy popped outside. That's when our DE met BEN MASON, and if you turned on the sound you heard the crack this made as the DE was suddenly very much kicked.

There's also the chance that the guy replacing isn't going to be up to the challenge of a back out there in the space of edge. Often offenses will test teams that are playing to spill with end-arounds or jet handoffs with their fastest players to see if the linebacker or safety replacing inside-out really has the wheels to keep up. Spill technique is a tradeoff: are you more comfortable squeezing the run inside, or do you trust an unblocked guy against their ballcarrier in space. You'd better know what you're dealing with going in.

November 6th, 2019 at 3:05 PM ^

Who is going to be the first to step up and name their son Counter Trey (insert last name)?

November 7th, 2019 at 9:57 AM ^

Probably Denard Robinson Cook, if Brian has his druthers. Druthers, incidentally, is BPONEs squirrely 2nd cousin.

November 6th, 2019 at 3:05 PM ^

I'm a spill guy, and here's why:

- With any kick out block, the offense is trying to get down hill quickly. Spilling takes that away.

- Spilling requires the D to defeat one block at the point of attack, whereas squeezing requires it to defeat multiple.

Really enjoyed this one, Seth

November 6th, 2019 at 8:39 PM ^

Fast LB's are really the key to being able to play it this way. Without that, good luck.

November 7th, 2019 at 4:16 PM ^

As it turns out, you don't. You do need guys who read well and know their assignment. When you spill, the back has to radically redirect, giving the LBs time to get there. Mainly, however, when you spill you also have to have another unblocked defender (typically an overhang OLB or safety) to spill the RB to. Once the RB redirects outside, the unblocked player pounces and it's game over.

November 8th, 2019 at 7:48 PM ^

Who plays this technique with slow LB's, and has success? Genuine question.

November 6th, 2019 at 3:16 PM ^

Ok I'll bite. Is this going to help with OSU? I didn't see OSU or Ohio mentioned in the write up (of course, I only did a CTRL-F).

November 6th, 2019 at 3:24 PM ^

I think so? OSU runs a power spread scheme and spilling apparently works best against power concepts. But I'm not too sure, my understanding is fairly rudimentary.

November 6th, 2019 at 4:18 PM ^

I mean maybe though the other side of the coin is that your assignments with the spill have to be sound or you are risking giving up a big play like the Taylor run. Kinda of risky proposition when facing a team like OSU that likes to generate big explosive runs.

November 6th, 2019 at 5:45 PM ^

exactly, OUR D has to come up HUGE in that game to give us any kind of chance and not sure we are equiped with the right guys to do it.

can we get the 2016 D line back?

especially big Worm?

November 6th, 2019 at 5:09 PM ^

Great write up as usual. You should try to get these out on Tuesday so they don't get buried under UFRs.

November 6th, 2019 at 5:54 PM ^

I usually plan to post them on Tuesday afternoon TBH. I've had some house issues lately that required my attention, and then this week it's the bye and we moved everything for Ace's hoops day.

November 6th, 2019 at 6:24 PM ^

Great work again Seth. Thanks!

November 6th, 2019 at 6:19 PM ^

I've been coaching at the high school level for quite a few years and we typically spill everything. We see a fair amount of counter trey out of spread (including QB counter trey) and we tend to have smallish defensive lines and smart, active linebackers. In fact leading to this year we have had a string of all-state (at least honorable mention) Mike's who read quickly and were able to scrape over the top immediately. Most have or are currently playing some level of college football. We just told our defensive ends to step down on a down block and find the puller. By wrong-arming, they bottle up the 2nd puller and force the back to bounce into our wall. The wall was formed with the Mike, followed by our Will/Sam, followed by our safety coming down in the alley. A couple teams we play have tried to log that defensive end and ask the 2nd puller to lead around to the edge. It's not nearly as effective, however, as high school offensive lineman typically aren't adept at redirecting on the fly.

This year, we were going to be vary young at LB, including starting a freshman, so we moved away from the 4-3 and went to a 4-2-5. We still spilled on counter trey and were just "ok" at it. We just weren't as effective because we didn't have the quality at LB that we have been used to.

Anyway, great write up. I really enjoy these as a coach.

November 6th, 2019 at 9:17 PM ^

I saw what looked to me like a surprising lack of wrong-arming in the clips. Do you know whether that’s a newer trend, to have the end man spill while maintaining normal technique? It seems like it would still constrict the hole without causing as much detritus on the way outside, which you’d ideally want.

November 7th, 2019 at 3:12 AM ^

What is wrong-arming?

November 7th, 2019 at 8:21 AM ^

Defenders are usually trained to keep their outside arm free, so that they aren't ever scooped or hooked. It's a way to make sure you're staying in your gap. So, if they are playing it straight, the end usually keeps his shoulders square and keeps that outside arm free. He has to, because his help is inside, and he might need that outside arm to tackle a running back bouncing outside.

With the wrong arm technique, he attacks the puller with that outside arm. This allows him to take the puller on more effectively, makes a kick out much harder, and usually causes a bit of traffic because the pulling and running lanes get all jumbled up around the pile. The guys in the clips are getting inside of the puller, but they aren't really attacking him with the outside arm the way you used to see. On some plays, they jump so far inside that they do effectively spill the ball, but they also make it a much shorter edge. The back spills, but they don't force him to flatten out and stretch it as far as you'd want, since the wider you make him go, the longer time he's spending behind the line of scrimmage.

I'm very certain this is a rambling, incoherent post. I'm on here much earlier than I usually am and my brain isn't kicking in. I might edit this later for clarity.

November 7th, 2019 at 8:24 AM ^

That is certainly something that Don Brown has talked about. He calls it 1.5 gapping. Don doesn't want to miss opportunities to blow an OL upfield. Denting the run is just as good as squeezing it. And everyone runs so much zone that getting too far inside provides an easy read.

So this may just be something both defenses were doing because they were facing teams that are more likely to hit that b Gap. They want to shuffle inside further because the back is going to run you over first and doesn't want to get spilled.

November 7th, 2019 at 11:59 AM ^

Once again, you are the best. No offense to the others.

November 7th, 2019 at 4:31 PM ^

We taught wrong-arming followed by turning up the field and extending arms with shoulders square in order to take away cut-back lanes. As long as their hips are inside, starting with playing square and using the hands like Brown does accomplishes the job and the spiller can still shed and pursue.

November 6th, 2019 at 6:33 PM ^

Love the picture of McGrone. He's levitating!

November 6th, 2019 at 8:39 PM ^

Good shit, Seth.

November 7th, 2019 at 10:36 AM ^

God, Denard was terrifying.

Comments