Neck Sharpies: What Is Counter Trey

This series is a work-in-progress glossary of football concepts we tend to talk about in these pages. Previously:

Offensive concepts: RPOs, high-low, snag, mesh, covered/ineligible receivers, Duo, zone vs gap blocking, zone stretch, split zone, pin and pull, inverted veer, reach block, kickout block, wham block, Y banana play, TRAIN, the run & shoot

Defensive concepts: The 3-3-5, Contain & lane integrity, force player, hybrid space player, no YOU’RE a 3-4!, scrape exchange, Tampa 2, Saban-style pattern-matching, match quarters, Dantonio’s quarters, Don Brown’s 4-DL packages and 3-DL packages, Bear

Special Teams: Spread punt vs NFL-style

So counter trey and its counter, BASH, are a pair of offensive concepts we're going to see more of, possibly from and certainly against Michigan. While things like it were part of the Single Wing offenses of the early 20th century, Tom Osborne's Nebraska teams really made Counter Trey a staple of power running. Michigan ran a bunch of counter under Drevno, and while they moved away from it last year, it has come up often lately in opponent scouting, most prominently in the Maryland offense when Mike Locksley was the OC. Since Locksley is now their HC, and because I know Gattis saw it plenty under Locksley last year, and Ohio State was doing it a bunch last year, I figured it would be a good time to cover these concepts so you can ID them when they come, starting with the ol' favorite, Counter Trey.

THE CONCEPT:

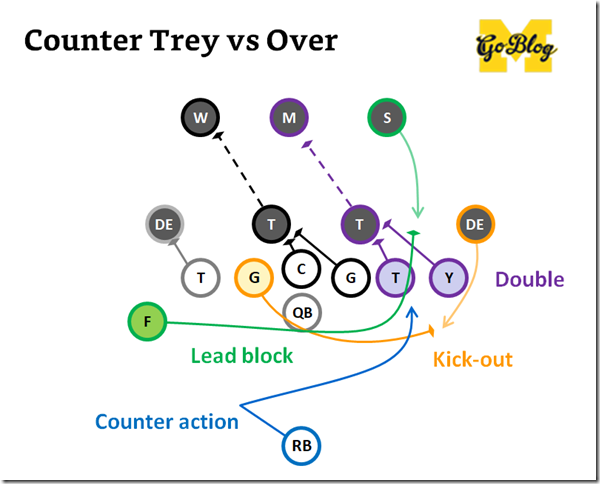

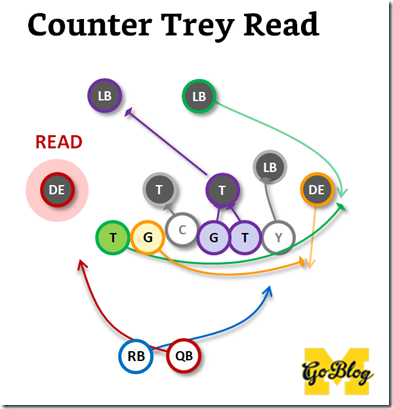

Counter Trey is a slow-developing counter run where you block down on the playside tackle and pull multiple guys from the backside for the two crucial frontside defenders: a guard to kick out an unblocked edge defender, and another guy from the backside (usually a TE or a tackle) to lead block into the frontside linebacker, with the back cutting off that block in the hole.

The plan here is to 1) Block down on the playside tackle, doubling to the MIKE, thus setting the inside wall of the gap. 2) Kick out the playside DE with the backside pulling guard to pry open the other side of the gap, 3) Bring a second puller (backside TE or OT) as lead blocker through the gap to take out the playside LB, and 4) Have the running back take a false step to freeze defenders to the backside, then cut behind the second puller and follow into the gap.

This definition gets controversial because it has expanded over the years. Voters in my informal twitter poll were split evenly between the definition above and any play with counter action and a puller, with a pedantic handful who stick to Osborne's original terminology. For our purposes I use the definition by Ross Fulton…

Anything that trades the responsibilities of power, such that the backside guard is kicking out and the backside T or Y-off is leading

— Ross Fulton (@RossRFulton) July 26, 2019

…plus counter action.

"Counter" in this sense refers to the initial motion of the back(s)—the running back will start the play with a short step counter to the flow of the play, serving as a fakeout to freeze any linebackers reading backfield motion, plus something to do in that second while the blocking is getting set up. "Trey" came out of Osborne's terminology for combination blocks: "Trey" meant a tackle+TE double-team. "Deuce" was a guard+tackle, and "Ace" was center+guard combo. I'm sure you can dig up a coach who swears a T/G double-team is "Counter Deuce" but to most "Trey" means backside guard->kickout+backside lead puller, kind of like how "secondary" has lost its meaning as "second level of defense" and become synonymous with defensive backs. As you can see in the drawing above, Osborne's terms made sense in a world full of fullbacks and tight ends. As we're about to find, this concept is so adaptable that you see it all the time today with no such things.

[After THE JUMP: How to spot it, how to defend it, what they do with it]

--------------------------------------

HOW TO SPOT ONE IN THE WILD

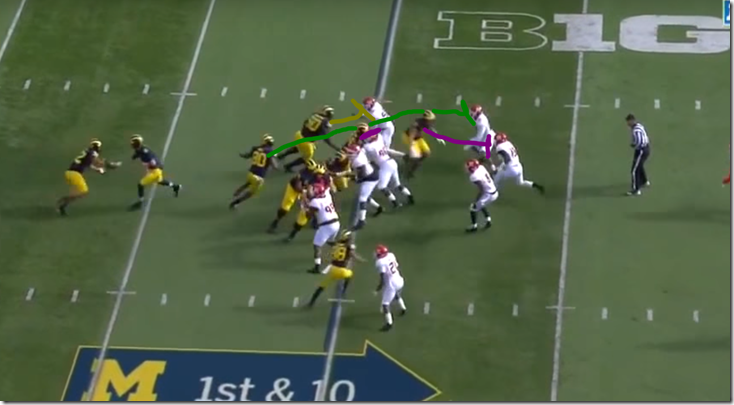

A canonical example from Michigan's BEEF period:

Note which side all the BEEF is before the play, and which side they're all going.

From up high it looks like a jumble of people in the middle as one side caves in and the other side comes around it.

Here's another that really demonstrates why you have that guard making the kickout block. Watch what happens to poor #92 standing on the "ADVOCARE" ad, and how that creates space for Evans to get around McKeon's statemated lead block, and ditch the safety trying to tackle for no gain:

Now watch again and see which direction the linebackers move first. From a defensive perspective, you see that back stepping like he's going to run straight into the gap the pulling guard just vacated. An untrained brain registers this as either an immediate /downhill threat with few bodies around, or perhaps the first of many steps in a footrace outside (to the side where all the numbers were at the snap).

While your dumb ass is reacting to that, the guard you're supposed to be reading is now a bull charging at the unblocked backside end. Suddenly another blocker swings past you, the back cuts behind that second blocker, and you're left behind. As for your buddies on the backside, they're now dealing with a gap with a deep block down or double-team on one side, a serious trap block on the other, and a whole lotta beef going through the resulting gap. In film they'll tell you to read your guard, as if it was that easy.

It takes a lot of practice to run this play, however. The blocks all need to be timed well because ideally that second backside puller contacts the second frontside defender at the same second the RB is popping through. And getting that end man on the line of scrimmage trapped outside needs to happen before that EMLOS can fight through his block and gum up your works. Make those blocks too quickly and you give the defenders time to fight through them. Execute those blocks too slowly and the effect of the counter step wears off, and you've got a running back trapped in the backfield with unblocked defenders.

DEFENDING IT

If you're new here, my theory on defending offensive concepts is you can beat any play with sound football (execution), or by doing something unsound that's particularly good at stopping this thing (rock/paper/scissors), or with a fantastic individual effort (kicking ass).

Option A: Read your guard.

The weakness of Counter Trey is it's a long-developing run with a free linebacker roaming about. The counter step is designed to freeze the linebackers (watch Gedeon, the LB on top) while those lumbering backside blockers go all the way from one side of the formation to the other. If you're watching the running back, that's what happens to you. If you follow your assignments, at worst you'll be as out of position as your assignment.

The backside linebacker in the following example is in position to make a stop for no gain because he correctly reacted to Khalid Hill's pull across the formation.

#6 the linebacker at the bottom

This play was ultimately a success for the offense because Mason Cole did an incredible thing to save it. At this point however it should be dead because both MLB #15 and WLB #6 ignored the counter action and got playside as their pullers did. Michigan has two blockers for three linebackers.

(After this Cole hopped into the MLB, WLB#6 just stood there being all Rutgery behind the guy Cole engaged, and Hill assessed his guy was Corporal Upham and moved on to fight a safety. Upham got dragged for a few).

Note: most linebackers are going to shift a little with their backs, and trust their acceleration to make up whatever they lost to the pullers. Overreacting to your guard leaves you open to being messed with (#5 very read his guard). In general however, Counter Trey is a fake-you play that works because you lined up with a lot of beef on Side A, took a step toward Side A, then cut back to Side B in a flash. If you don't get faked, you should be in position to beat it.

Option B: Rock/Paper/Scissors

Offenses that run this have to be prepared for defenders who show up where their initial alignment doesn't suggest they're going to be. Slants can be devastating if they're not properly diagnosed. Twists where a defensive tackle is replacing one of the linebackers puts the guy you're supposed to singing to right in your mouth:

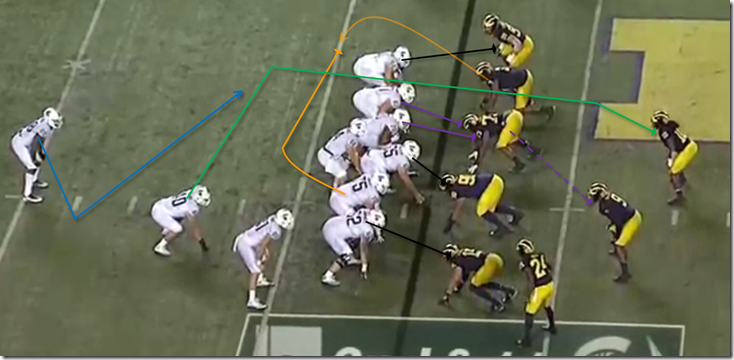

Watch Gary and Hurst, the two DL on the top.

State's in an unbalanced formation in this example but that doesn't really matter. What does matter is Michigan has an extra linebacker down because of it, but that's to be expected. They convert the TE to a kickout block and run it to "Deuce", IE double Hurst to McCray, and trap Gary.

What they don't expect is a twist with Hurst and Gary. This trades their roles. Hurst is now the edge guy the pulling guard is supposed to kick. Gary is now the guy the guard and the center are supposed to be doubling. Not that they have any idea.

Remember the first rule of double-teams: if the guy you're supposed to be doubling is in the backfield blocked by nobody, you're gonna have a bad time. Gary absorbs the puller right in the path of the back.

What Michigan did essentially was replace the roles of its defenders after the snap. There is no backside linebacker to flow to this—the stunt is all the defense you need.

You can do this with a corner blitz too, or to a lesser degree with anything that confuses the blockers' identification. Counter Trey works best against defenses that are getting too aggressive at attacking initial motion; it's not really built to deal with exotics. You've got key blockers departing their side of the line and tasked with reacting to whatever they find on the other side—multiple targets where they're not expected are unfair.

Remember though, you're hanging yourself out there. Teams that slant toward the perceived strength (IE side with lots of TEs) a lot get Counter Trey'd a lot.

Option C: Kick Some Ass

As with any play, there are opportunities for a defender to MAKE A PLAY. There are a lot of blocks here that can go wrong, and a lot of time before the play is out of a backfield for a great player to do a thing. The most common death of Counter Treys is the frontside linebacker wins against the second puller. Here's Khaleke Hudson shedding the tight end who came around on him, allowing backside pursuit to arrive and swallow a 2nd and 20.

#7 linebacker on the top

And jere's another example of this from the Cincy game in 2017:

The Bearcats had a 309-pound guy playing weakside end, and when Khalid Hill, the second puller, tried to pop that guy, Panda's hammer got the worse end of the exchange.

The second most common death is the frontside tackle beating a double-team. Just a stalemate there keeps the WLB clean to read his guard and get in position. A solid win forces the back to try to cut outside, where the trap block wasn't made to stand up that long. This example is interesting because Urban Meyer used his quarterback as the runner and his RB as the second puller. It's also interesting because Will Campbell did a thing.

DT#73, the second defensive lineman from the top.

Another common foil for power-type plays is that center vs. backside tackle battle goes quickly and decidedly in the DT's favor, thus disrupting the pullers' and back's path and screwing up the play's timing. I don't need to find an example right? You all can imagine Mo Hurst getting instant penetration and disrupting a puller right?

The other thing that often goes wrong with the backside guard's trap block is a defensive end who's reading the trap and coming in to defeat it. This could also go in the Rock/Paper/Scissors category if the coaches are telling their ends to crash, but when the end is doing it himself because he sniffed out the play, you just have to tip Eric Upchurch's hat to Chase Winovich.

#15 the guy with the long hair at the bottom of the defensive line

One more way to beat these plays that I've only seen the once is when the backside end also crashes in response to both blockers in front of him pulling, so that when the running back goes to get behind the second puller, the backside end is already in line. Y'all think I'm going to post a Gary clip right now but nope: watch the clip above again except this time focus on the DE at the top of the line. Hey, hey, Kwity Paye.

VARIANTS AND ADAPTATIONS:

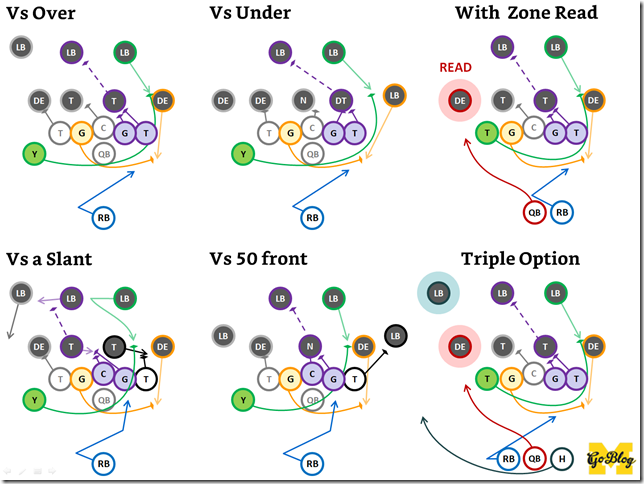

There are SO SO SO SO many. Offenses can pull the backside tackle, add a zone read, kick out an EDGE and run it inside, and add jets, pitch options, bubble reads and RPOs to keep the safeties out of their hair.

And you already saw how Michigan State likes to run it from an unbalanced set, all part of the ruse to get a defense focused on defending the side that looks like it has all the meat before the meat comes around to the other side.

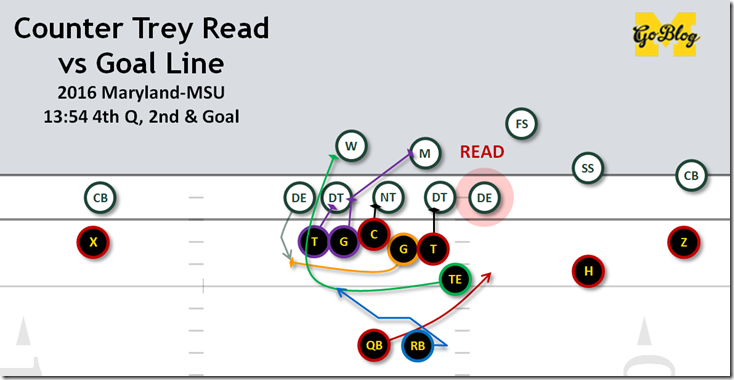

Of course it's been adapted to things that defenses do to it. Here's the same play from a shotgun versus goal line. Maryland is taking out an additional defender by reading the backside (but still bringing a guard and TE around).

The counter action includes a quick look-off from the quarterback. In today's spread world if you're an unblocked DE and the quarterback is looking at you, in most cases this means you've got to form up and play the option. That quick look is all the pulling guard needs to square up and get that kickout block. It's so quick in fact that the quarterback can still turn around and make a backside read.

But….the above isn't really what happened on this play. See if you can spot the difference:

The nose tackle here is trying to screw it all up by jumping into the playside A gap. Once that DT crosses the center's shoulder something interesting happens with the guard (in red):

No more playside double to the linebacker level. Instead the left guard picks up that nose tackle, and the center moves on to the linebacker. These are things good zone blocking teams are used to adjusting for, and thus the reason teams that run zone will still throw a deeply power play like Counter Trey into their arsenal. If you get a slant, there are ways of handling it responsibly to put the play to rights again.

ADAPTATIONS TO THE SPREAD

When spread teams adapted the zone read to it they used the backside tackle as a second puller, freeing up the "Y" to do whatever spread thing their coach's spread heart desired. Note this is play has the same timing as the two above but they're reading the backside DE instead of blocking him:

Joel Bitinio (#75) and Joe Thomas (#73) leading Crowell on a Sweep Read. Hue Jackson ran the heck out of this concept during the 16' season. pic.twitter.com/2KRQDemsab

— All22ChalkTalk (@All22ChalkTalk) July 18, 2017

Here we've got an example kind of like the setup for the Michigan-Michigan State play that Gary/Hurst twist blew up. There's no twist this time, but the offense is going to treat the LB like a kickout for the TE and run it to Deuce. With the LB taking an inside gap, the second puller tracks the playside LB outside, and the RB can cut in off the big victory on the double.

From here the possibilities are endless. What you've got is a basic running play involving your back and your offensive linemen, plus someone to deal with the backside DE somehow. You can add another back. You can flex the TE out into the slot, pulling a defender completely away from the play. Ohio State was running a sight read off of it. If the overhang safety (top safety on the hash mark) stays with the bubble guy, they run the play; if he doesn't, they throw the bubble. Or in this case they throw the bubble anyway because KJ Hill vs a safety is six:

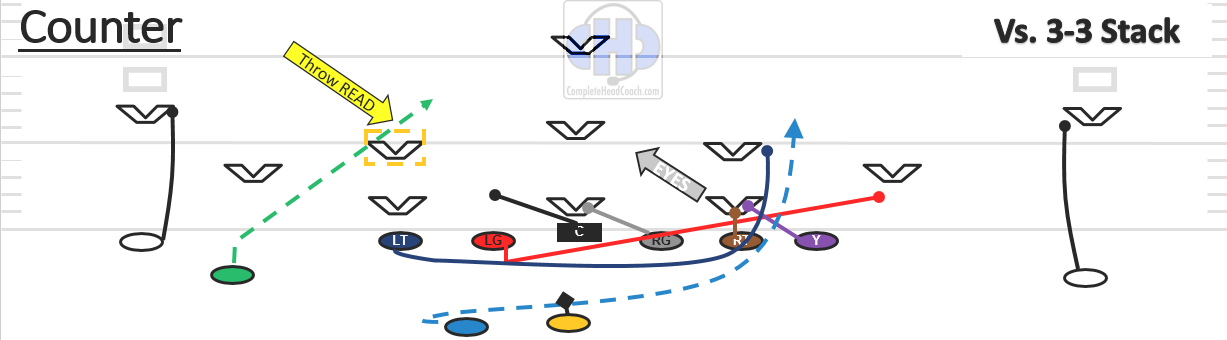

They run real RPOs out of it too. I was going to draw up the one Alabama used last year against the various 3-man fronts of the SEC but Complete Head Coach did it two years ago with high schoolers:

And hey, since we've got all these people about to cross each other anyway, let's get more traffic going in different directions by adding some jet motion. One of my go-to YouTubes for spread offense is Coach McKie and he did a great job recently of talking through how his spread runs this with jet motion.

The jet motion really opened up Counter Trey to the world of spread. Remember the Winovich/Paye kill against Wisconsin earlier? Look how Michigan decided to punish Florida for that in 2017:

Jet motion has the effect of loosening everything up in general, putting those safeties into a roll instead of letting them line up on the exact spot their coaches dictated, forcing the linebackers' eyes to the backfield, messing with all but the most basic fits. But as we'll see next time, when Chip Kelly starting using jet motion at Oregon, he found the perfect complementary play to Counter Trey. One that's 'sweeping' through college football today.

Good stuff as always!

"good shit, Seth"

Excellent work, thank you!

Seth,

Color coding your description to match what's being described on the play diagram was a stroke of brilliance. So simple and it makes it that much easier to digest and understand the concepts you are describing. Great job! This is one of my favorite segments on the blog and I look forward to them.

Also, using the same color to denote offensive personnel AND the defensive player they are blocking/keying on is incredibly helpful. When everything is the same color on a play diagram, it's harder for a football novice like me to digest, but the different colors really help me mentally compartmentalize the different matchups while still seeing the play as a whole. It's a really good teaching tool and it's cool to see how you are innovating each time you write a new Neck Sharpies.

Wasn't counter-trey the mainstay of Joe Gibbs' rushing offense?

Yes, rode it to a couple Super Bowls as a matter of fact. When your blocking works perfectly and your QB is competent downfield, basic 1990s football offenses are hard to stop.

Yes, I remember Ohio State.

Indeed. This was the Hogs' favorite play. People remember them as big dudes but they were actually small even for their time. But they were excellent at pulling and playing off those backside combos.

I love football!

Good god those HS defenses are just terribly, terribly coached. Space Coyote, Magnus you got get down there and fix them!

I remember Brady and Henson handing off to A-Train with this similar play.

It worked very well.

And Musberger bellows, "H e r e c o m e s t h e AAAA-T r a i n!"

Can anyone link me the neck sharpies Seth did post spring game with Dylan running that option play? I could’ve sworn it was neck sharpies but i can’t find it. I think that concept with pin and pulling is similar to this

2 questions/observations:

1) Obviously each coach has an emphasis or base to teach out of. Does Don Brown try to call to a more RPS style? I think his approach is different than having players play sound within set assignments. For example, in the quarters defense that Brown has dismissed as trendy, it seems like players are drilled in repetitive assignments/tasks that change depending on how the offense is read. By contrast, Brown seems like he has more packages and a diversity of play calls to try to get ahead of the offense. This looks great when it works, but can also go the other way if the offense stays ahead of you.

2) Is there a reason that defenses don't shift constantly pre-snap to try to mess with an offense's, especially no huddle, check the sideline, spread's reads? Or at least align in a way to trap the offense into doing what the defense wants (for example to play 5 in the box but crash defenders into the box to stop the inevitable run)? To be clear, I'm sure both are done, but it seems like defenses either get caught in obvious positions often or play too aggressively and leave themselves exposed. A lot of these offenses are predicated on what the defense does, and it seems like you could train a defense to use that info against those offenses.

Excellent job on the counter trey and sorry if my questions/observations are off point.

Don Brown's defensive philosophy is he wants to dictate terms and force you to check into the things that his players are ready for. He doesn't want to be reacting to the offense he wants the offense reacting to him. Quarters is the RPO defense. You read what the offense does and react. This is akin to what Bo ran at Michigan.

Pro defenses shift all the time but first you want to make sure you are playing sound and prepared for what's in front of you. Also it's the offense who gets to call the plays so normally the defense is shifting around to make sure they are sound against whatever the offense just shifted to. Defensive motion before the play is more about messing with the quarterback's checks. If the offense is taking too long a linebacker will come down like he's going to Blitz. Sometimes that's a fakey. There are a lot of little games the players are playing between each other but for the most part you have to think of football as a large mechanism where everybody has a role to play. Too many moving parts will confuse that. A defense where 11 guys are just out there trying to make plays is not actually going to make very many plays. The stars are the guys who can cover their assignments no matter the circumstances.

We used to kill people with this play in high school. we ran the run n shoot so our base set was 5 lineman, 2 wing backs off the tackles and a full back. we had a simple trap play where the guard pulled called popcorn trap. then we had buttered popcorn trap where the backside tackle followed the guard and led up through the hole. it was awesome. our line was bigger than everbody.

How did you block the run-and-shoot?

August 6th, 2019 at 12:27 AM ^

It's me! An article ALL ABOUT ME!!!

Comments