Neck Sharpies: Getting Out of a Scrape

Last week in this column I talked about how the changes to Michigan's running game under Gattis seemed to be mostly about adding a read to it. One week later, at least among fans who know the first damn thing about Army, we're all grumbling about about how Michigan reversed the gains of their Gattisization by dorfing the reads.

To be sure, there were plenty of plays where Shea (and one where McCaffrey) had a keep read and handed the ball off. It's also pretty evident—despite what Harbaugh said in the presser—that Patterson was playing hurt. Also later in the game Army knew Michigan wanted to avoid passing and started bringing their cornerbacks on blitzes off the edge.

However, on re-watch, I noticed a lot of other plays where the DE crashed but Army was really taking away both options with what's called a "Scrape Exchange." Maybe showing these plays, what Army was doing, and what Michigan could have done in response, will ease some of the whinging?

----------------------------------------

1. What's a Scrape Exchange?

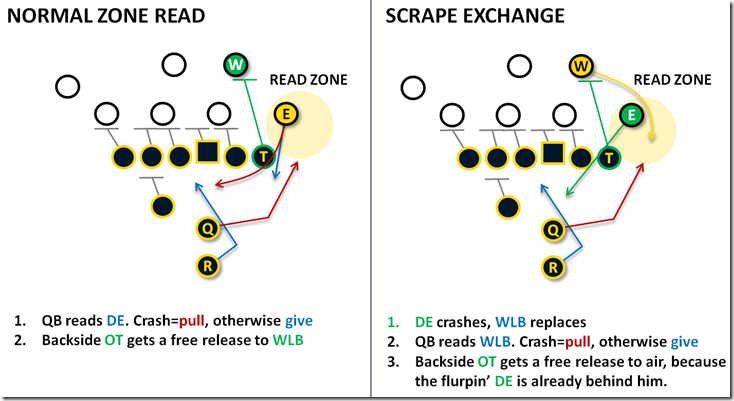

It's a defensive "paper" call to the "rock" of the zone-read option play. Essentially they're flipping the jobs of the two backside guys, having the DE crash inside while an LB loops into the spot the DE formerly occupied.

The win for the defense is the green (i.e. the B gap) block in this diagram. The offensive play is designed to get that block accomplished with a tackle releasing on a linebacker. By exchanging jobs, the defense wins the block and can force a read right into it.

I covered this a few years back when we were meeting Don Brown, and again when Iowa adapted to Michigan's Pepcat package (and Microsoft still included their full video editor with Windows). Unfortunately something on our site is breaking the links to old images at the moment, but you can probably get the gist just from the video with the Bear vs. Shark song on it.

[After THE JUMP: We have the technology, but do we trust it?.]

----------------------------------------

2. How Can the Offense Respond?

A scrape exchange is a paper play, and you can always scissors those. FishDuck, one of the first X's and O's guys I got into, has a whole video on scissors plays for the scrape exchange. If you're interested in those, watch it, because I'm going to skip past this after.

To his list I'll add Belly, a zone read where you double the backside DT to blow him out and then truck stick the WLB. Belly is certainly in Michigan's offense, but might have been iffy against Army because of the weird way they align.

Those are great to have in your offense but not very useful once the ball is already snapped on your zone read play and the opponent has a scrape exchange on.

----------------------------------------

3. How Can the Offense Build a Response Into their Zone Read Play?

Fortunately you're not screwed. Double-fortunately, unlike in 2016, Michigan now employs the guy who once gave a coaching clinic on this (HT: Smart Football) while working for the baddies (warning: language NSFW):

The relevant part starts at 22:15, but you can go back to 12:00 and 19:45 to catch the coaching points on a normal zone read (and the part where Ed admits he had to change up his terminology because OSU guys aren't as intelligent as the players he used to coach).

The way Warinner coaches this, the tackle's first step is to read and react to the defense. Meanwhile the quarterback's zone read—just as Rich Rodriguez always said—is reading a zone, not a player. If the DE steps out of that zone, e.g. by scraping inside, the quarterback reads the linebacker stepping into that zone, and that means give. I had a hard time pulling an old example from a game you want to be reminded of, so here's Mark Huyge (the left tackle) doing it on a play that was blocked well for a frontside run until Michael Shaw inexplicably bounced out of the lane the play created.

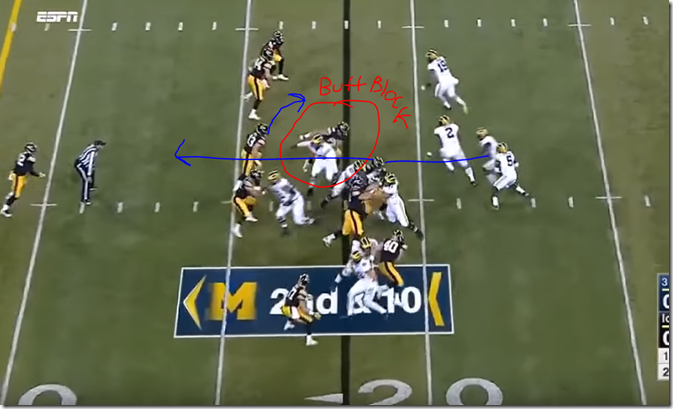

Sometimes that exchange happens too late because the T has released downfield. He can still stop and execute a Butt Block. I don't have any good clips of this but we can screen grab from the 2016 Iowa clip and pretend. Basically the tackle sees the WLB cross his face, stops, and just walls off the DE like he would on a rebound in basketball. Now you've got the WLB outside, the DE also walled outside, and the QB will see the WLB, hand it off, and send the RB through the butt block.

(Relevant to Michigan but not to this play: in the video Warinner notes that he has the T block that LB "for the running back." In other words he wants the block on the linebacker to be good for a handoff, not just a seal in case the QB keeps it. It's harder to execute but better for general use.)

----------------------------------------

4. What Was Different About Army's Defense?

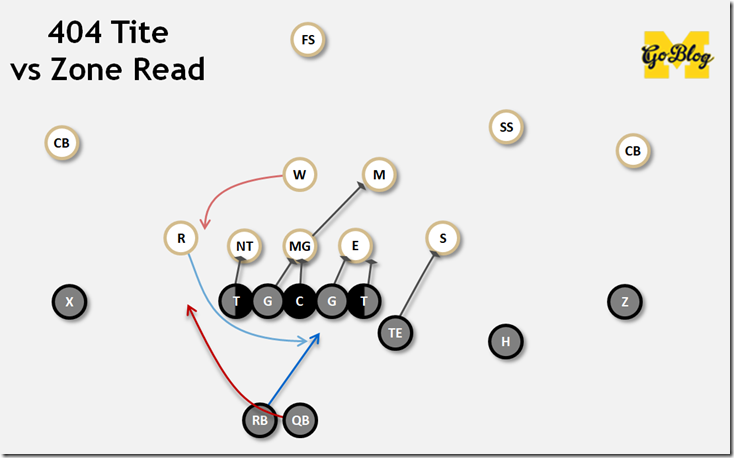

Army ran a bunch of these against Michigan's Arc Read zone, which they correctly identified as the Wolverines' best play. But what Army does is a bit different than your standard 4-3 defense's scrape exchange. Their 404 Tite system is designed not just to get that exchange, but to make the exchange optional depending on how the offense is blocking it, forcing a give, and forcing the back into the teeth of their defense.

What was so disappointing from a game theory perspective is that Army's defense more or less wants to play like this. Their 404 Tite was designed specifically to gum up the frontside gaps with DL and put multiple edge defenders in space on the backside to stop spread games. This is what happens when you run zone read against a 404 Tite:

See? It's not a 100% scrape exchange. The Rush end (we'll call him R today) is able to squeeze the read until the WLB comes around behind him, delaying the handoff and ultimately forcing it. The offense then has no angles on the backside, and is forced to run into whatever gaps they can create on the frontside, which won't be the gaps they normally like to run into because there's a thick DE playing over the tackle they want to run behind out there. Also the defense knows this and has the MLB gunning for it.

These exchanges were more like stacks—lining up behind one another—but the result was similar: two guys hanging out there when the quarterback goes to read, and everybody else fighting their way playside to stop the running back.

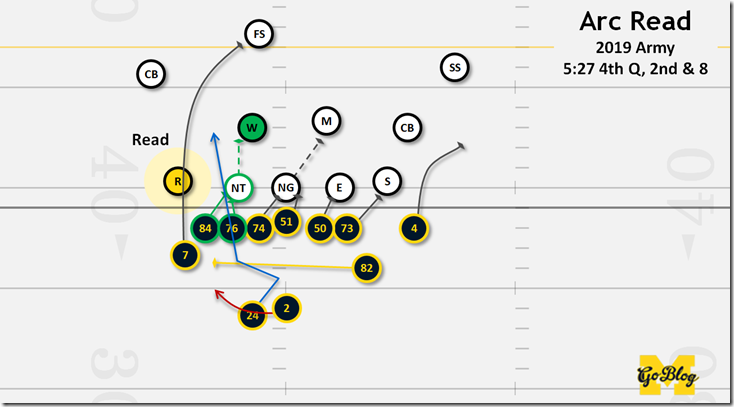

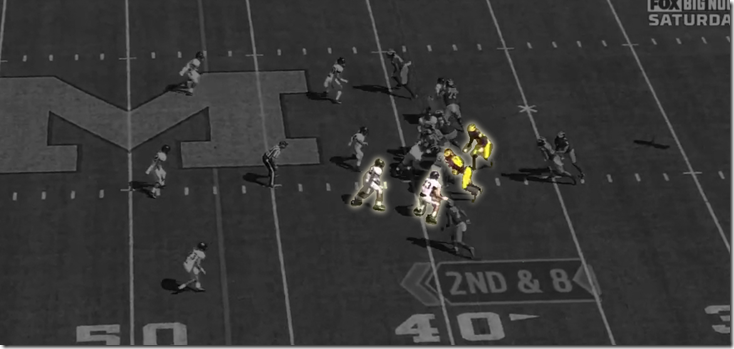

Army is able to play like this from multiple alignments. Here's an example from Michigan's final 4th quarter drive. Michigan wants to run the ball and kill clock because if you get Army in any kind of passing situation they're dead meat. Army knows this and is stacking eight in the box. Better to give up a touchdown than a field goal with under 2 minutes left. So this is already a Rock/Paper/Scissors loss for Michigan as it's drawn up.

You can see what Michigan wants to do: read the backside EDGE defender (R), seal the backside T and WLB inside, and either split zone inside the R if he forms up outside, or arc zone around him if he gets inside. Army is going to gum this up by having the R dive inside and the WLB jump outside. Essentially they've flipped jobs, and McKeon now has to deal with a green guy outside of him.

At the moment of the read Army has not one but two backside guys protecting the edge Michigan wants to arc out of. They're also in position to exchange, but not fully exchanged, and also shuffled at the line of scrimmage rather than upfield where they would be easy to trap block. This would be a very difficult block to get right:

Wherever McKeon goes, the LB will go in the other hole, and the R will do the opposite. Either way the backside is closed, and Patterson has to give it to the running back to get what he can frontside. Where Army has that extra defender. Play dead.

5. What About the Corner Blitzes Into This?

The corner blitzes were Army selling out against Michigan's arc read plays, gambling that Michigan was running some kind of zone read run and giving up entirely on the idea of defending any kind of pass to the flat.

If the defense adds a corner blitz to a scrape exchange and catches you on a read play, you're dead meat, especially when he times his blitz so well that he's in the neutral zone at the snap but would have to be named Khaleke Hudson to be called for it. Short of—I dunno, pitching it to Eubanks?—this play call is doomed.

"What are you gonna do, stab me?" –Man who wasn't stabbed for some reason

The Harbaugh offense nerfed those games by play-action passing and putting the ball in the back's hands so fast that the corner blitz was just adding a useless chaser to the backfield. The Gattis offense is supposed to nerf those games by putting the defense in space. Remember that play in the spring game when the running back ran one way on a flare and the quarterback was the pin & pull ballcarrier? That punishes teams that try to pull what Army was pulling most of this game. Michigan threw it to the back in the flat once in the 1st quarter, then forgot about it. Army then got to go balls out against Michigan's backfield without fear of giving a chunk to a play Michigan should be running a lot.

Michigan also tried a lot of unbalanced stuff in this game, covering the tight end on the strong side and having no pass threats on the weak side. Army allowed it, leaving the cornerback to that side as an overhang LB, which was plenty to force Patterson to give. This invited a CB blitz but since that didn't occur, Michigan got to enjoy greater spacing on the frontside a bit and used that for a decent gain.

After that the gimmick was up.

----------------------------------------

5. Well Then How Do You Beat What Army Does?

Get more players to that side than they have and don't flub the read. By putting a slot receiver on the backside here, Michigan has forced the weakside defender into a run/pass quandary. He's got to stay outside, the DE can again be the read guy, and with no more crashing end the give is a good play again:

But you have to still make the read:

Michigan now has their slot receiver on the backside, and Army has responded by shifting the Tite front over to something more like a 4-2-5, except the WLB is now being pulled outside by the slot receiver. Because he doesn't want to get too far outside, Michigan now has flanking numbers to the back side of the formation. They could bubble out to the slot, or just use that to deliver the quarterback to the safety with a WR crack on the WLB. It's there, and Patterson keeps. Booooooo.

This should not have been a give:

I thought this was a clever way to keep the numbers to the intended play side while moving Army to attack the formation's strong side. It works too: their entire front steps toward the bottom of the screen while Ronnie Bell's orbit motion is reversed into a zipper. The DE has shuffled down the line of scrimmage like he was doing all game, and now Shea has both a TE escort and a pitch option versus Army dudes. He hands it off. Booooooo!

You can also just shift the game to the frontside. This also should not have been a give:

Look at the numbers Michigan has in this clip: 1 has to respect the jet; 2 has to play the run and deep safety; 3 is all the way on the hash and has to get around the H-back, Eubanks. The WLB is so far inside he's not even in read position anymore—that's the damn cornerback, who's got a jet to worry about. Keep the ball!

In summary, this game's running woes weren't just about missing keep reads. Most of the quarterbacks' reads were gives forced by how Army plays defense. The frustrating thing is when Gattis gamed up a keep read for big yards, the quarterbacks still gave.

September 11th, 2019 at 8:59 AM ^

For years I've been watching other teams—frequently against us—have their QB sit back in the shotgun, take the snap, and within two seconds throw it to a WR or a slot running in space out in the flat or over the middle. Because the play happens so quickly, there's rarely enough time for a meaningful pass rush to happen unless a blitzing LB or S times the snap perfectly.

Are we not able to do that?

September 11th, 2019 at 12:59 PM ^

Thank you as always Seth. I'd love for some of the Chicken Littles (and Michael Spath) to give this a read.

September 11th, 2019 at 1:25 PM ^

Yea no bueno, good write up though, thanks for the insight.

September 12th, 2019 at 9:01 PM ^

I think you guys may have forgotten the richrod response to the scrape exchange. It was this, and as a simple adjustment to the run game it was good:

Allow the LB to scrape away from inside to outside. Bring the H back across to stone the collapsing DE. All other blocking stays the same and the tailback takes and screams directly upfield into the space vacated by the scraping LB.

There is probably some wicked play action off of this as well, but in 2009 ND, the richrod response was extremely effective just in the run game.

Comments