dime defense

[This article was originally published on December 15, 2020. Two years and two weeks ago Michigan was in search of a new defensive coordinator, and possibly about to be in search of a head coach. The hottest new defense for stopping the hot new spread offenses proliferating through the Big XII was that pioneered by Iowa State's Matt Campbell and his DC Jon Heacock, who were the hottest names at the time for Michigan's opening/hypothetical opening. That was enough, at the time, for your hot new football strategies-obsessed author to write a primer on the defense, what personnel it uses, and how it works.

This 3-3-5 Flyover defense has since been adopted, more or less intact, by TCU coordinator Joe Gillespie. TCU runs it with "more interchangeable" linebackers, which is to say they couldn't find a faster WLB to fulfill that role. This relative lack of athleticism in the ILBs in a system that demands it from at least one of them is the reason why, as Alex Drain identified in FFFF, TCU has struggled with receiving RBs, passes up the seam, and edge attacks when their LBs are whipped in different directions.

I am republishing this article as a companion piece to Alex's film analysis so you can understand better what they're trying to do, and how that's led to many of the things Alex observed. Plus, only 5,160 of you read that piece, which is about how many read my CMU preview yesterday, if you're wondering how the football of the last two years has affected MGoBlog traffic. ICYMI the first time, here's the Soup Defense.]

------------------------------

Iowa State head coach Matt Campbell and his defensive coordinator Jon Heacock were hot names in coaching circles long before Michigan fans began to consider bringing both or one them to Ann Arbor. I don't know if that's happening—honestly I'd place the odds under 10 percent. But it's a good excuse to talk about their three-high "Cyclone" or "Flyover" defense, why it's been successful against the high-flying spreads of the Big XII, and what offenses are doing to adapt to it.

THE NATURAL HISTORY OF FOOTBALL DEFENSE

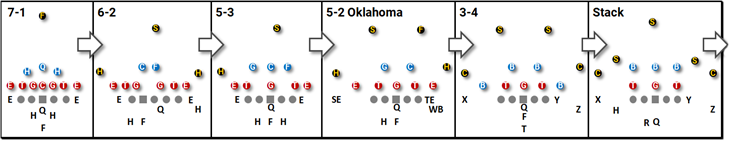

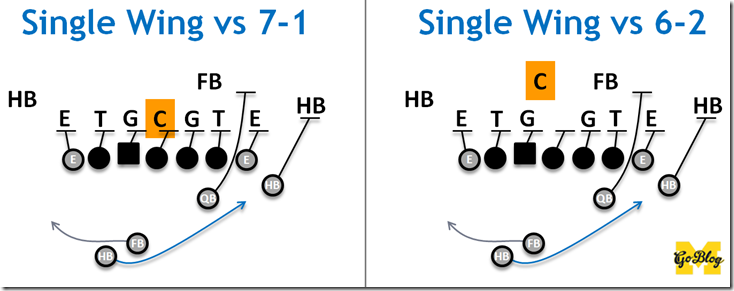

When football was young, you could barely tell which side was on offense. But the advent of the single-wing caused spacing problems, solved when Michigan center Germany Schulz moved himself off the line of scrimmage. The 6-2 defense was originally just an anti-spread weapon but gradually became the base of most teams.

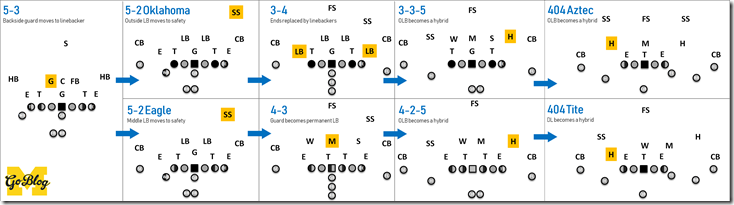

Virtually every defensive evolution since has followed this same pattern of converting thicker players up front into leaner and faster players further from the line of scrimmage. The 5-3 came about when they had to move a guard back to create a third linebacker to stop the Wing-T and early passing offenses. When pocket passing became possible due to rule changes, defenses answered by using hybrid linebackers as second safeties, then bowed to inevitable and called them safeties; the 5-2 was born. When that wasn't enough speed they converted the 5-2 variants into the 3-4 (replace both DEs with LBs) or 4-3 (replace the NG with a 3rd LB). Spread football in the early 21st century replaced fullbacks and 2nd tight ends with slot receivers, forcing defenses to become every-down 3-3-5 and 4-2-5 nickels.

That's where we've been.

THE PROBLEM

The reason ISU went to this defense was the Big XII is home to the spreadiest of the spreadiest. Tom Herman at Texas, Lincoln Riley of Oklahoma, Mike Gundy of Oklahoma State, Chris Klieman of Kansas State, Matt Wells of Texas Tech, and the offense WVU's Neal Brown inherited are all state-of-the-art spreads based on 4-wide sets, and stretching you vertically and horizontally. Baylor's Dave Aranda and TCU's Gary Patterson are defensive guys at heart but their OCs run similar spreads. Only Les Miles of Kansas—figures, right?—runs an offense more predicated on Bo's principles of moving people where you want them.

[After THE JUMP: The next evolution?]

Fielding Yost had a problem. After four years of dominating college football many other teams had learned his speed-'em-up and spread-'em-out offense, and were coming up with new ways to use the attack. Single-wing football was taking over, and the old way of matching seven players on the offensive line with seven defensive linemen was starting to get run around.

The guy who solved it for him was center Adolf "Germany" Schulz. Rather than limit himself to taking on interior linemen when the ball kept going outside, Schulz stepped back, ready to launch himself back at the interior if need be:

If you're wondering where's the safety, he had to hang way back in case the offense punted.

It wouldn't be the last time defenses learned to counter offensive innovations by pulling back box defenders.

S/O to Iowa State for finishing 22nd in the country in Rushing S&P+ while employing a 4 man box as often as possible. pic.twitter.com/iwrd1BfsfN

— Seth Galina (@SethGalina) May 8, 2018

As forward passing took hold, Crisler and his contemporaries began playing with lighter guards they could move off the line as a third linebacker. When teams starting regularly splitting ends out as wide receivers, Bump had to turn one of those linebackers into a second safety. As the I-formation took hold Bo had to replace his ends with OLBs to match their speed to outside runs. As shotgun three-wides became the norm, so did fifth defensive backs like Don Brown's Viper. And if you think it stops there, you're still living in the 2010s.

click for big

Michigan's 4-2-5 defense was good enough to match up with most of their schedule, but you don't need to be reminded of the times when it got got. You recall Saquon Barkley on McCray. You remember Devin Gil hopelessly chasing Ohio State's scatback DeMario McCall. You probably remember Florida quarterback Feleipe Franks running into acres of space. And if your lizard brain didn't go to "RECRUIT HARDER!" you've probably begun to understand what that signifies: The reign of nickels is over. The time of the dime has arrived.

[After THE JUMP: Why elite spread offenses torch us, and how we can use Woody Hayes's defense to stop it]

41