Neck Sharpies: Outside of This

If you were around for the first Rich Rod year, when Michigan's offensive talent wasn't on the same level as most of their competition's, you may remember there would often be some cute trick in the Wolverines gameplan. This gambit would work for a quarter before the defensive coaches got a moment to explain what's happening. Their answer would stress another part of the late-aughts Michigan offense that couldn't take it, and that would be that. Still, the yards and scores all counted. Several of the results also made Paul Nelson's legendary 2009 hype video, which has since become this site's anthem.

Now that you've watched that to remember how far we've come, turn back to 2:54 for the Purdue/Penn State sequences. Michigan actually led Penn State 10-0 in the 1st quarter in 2008. They lost 17-46.

Fast forward 15 years, and Michigan's the heavy favorite adjusting to some cute gambit in the 1st quarter before shutting it down with a simple reaction. Minnesota's trick, which led to a 54-yard field goal attempt, was actually pretty similar to Rich Rod's against 2008 Penn State, another team built on the strength of its defensive tackles.

The base play Minnesota was using was zone stretch. Or outside zone. We never decided on what to call it, but it's the second time we've talked about it this year because Michigan spent the UNLV game trying to rep it. When that happened I posited that Stretch is tough to add as a second pitch to your running game because it takes a lot to get right. Minnesota uses it as its #1, and found ways to repeatedly crack Michigan's front by using backfield motion to stretch the of horizontal space Michigan's linemen had to cover on their own.

The short explanation is Minnesota attacked the way Michigan prefers to play the run without committing much material to it. Minter's defense likes to set its edge and leave their defensive tackles to keep things under control in between them until the ball is handed off. This allows the linebackers to pursue passing targets and the edges to remain in position to rush the passer, stressing the DTs to gain a measure of immunity to play-action. Minnesota was using motion from their tight ends and receivers before and after the snap to spread out those edges, which overstressed the tackles, and created wide lanes before the linebackers could get back to help. Hit the jump and I'll show you how and why, and how Michigan responded.

[After THE JUMP: Stretch in Space]

ESTABLISHING THE TENDENCY

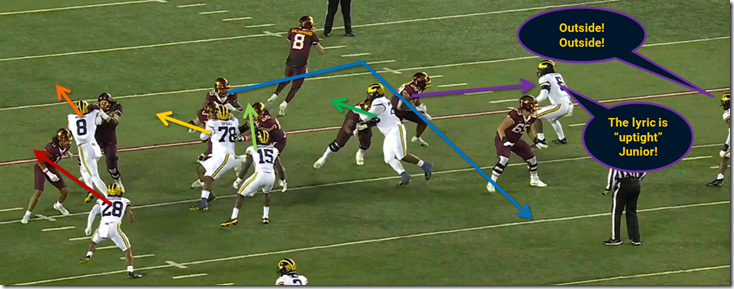

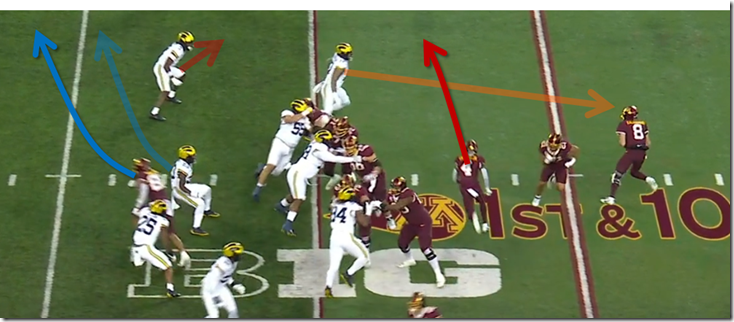

Just as we saw with Rutgers (the throws underneath Cover 3) and Nebraska (the slants), the first time Minnesota declared what their Thing was gong to be was not with the thing itself but the counter to it. The Gophers motioned a receiver across the formation, then motioned a different guy the opposite direction and ran play action. Michigan was all over it.

After you've watched this play, rewind and watch what happens with the linebacker level pre- and post-snap.

1. The F-Tight End's motion brings Makari Paige (#7), the box safety, inside the formation like a linebacker while the other two ILBs have to widen with his motion.

As he continues outside post-snap, Jaylen Harrell and Mike Sainristil widen as well.

This is messing with a fundamental rule of Michigan's defense: do not get edged. Run or pass, if the offense is going to race material outside Michigan wants to have a defender responsible for that guy who's staying on his outside shoulder at all times. As he passes each gap, the defender in that gap has to shift one gap over to make sure whoever's at the end of the line is free to keep the play inside his shoulder.

Of course as soon as the snap comes WR#4 on the bottom starts motioning across the formation the other way. The DE on the top, Braiden McGregor, widens a bit as he gets read on what looks like a zone read option. Paige spots the WR and has to reverse course, returning to his role as a box safety.

This attempt then resolves into play-action. As soon as he realizes this Barrett, the WLB, stops moving down towards his run gap and picks up the inline tight end that Minnesota was really trying to hit here:

With everyone covered and McGregor coming up to pressure, Kaliamanis turfs it. It's a successful defensive play. But Minnesota was able to confirm how Michigan was going to react to threats leaking out of their edges. And one pick six later they would put it to use.

HOW MICHIGAN WANTS TO DEFEND STRETCH

We've spoken several times this year in UFRs and whatnot about how Michigan's leaning on their DL to get away with extra coverage. This worked very well against the Bowling Greens and whatnot who major in Inside Zone concepts and couldn't get any movement on the Michigan defensive linemen.

The way they like to do this is to set a hard edge with a bigger force player, preferably the playside DE, then have all of their linemen keep theirs on the line of scrimmage, shoving the blockers—and with them the ballcarrier—towards this wall, until the RB's "gap" is just a pair of friendly shoulders squeezed together. Once he's hemmed in, the linemen and whatever linebackers want to join the fight can shed their blocks and pick out limbs from the ballcarrier to bring back to their dens. Watch #17 Braiden McGregor on the bottom set the edge, the DTs reset the line of scrimmage, and the back get trapped in the squeeze until the WLB and the WDE arrive from the backside.

The first time Minnesota ran stretch they didn't have any frippery attached, so we got to see how the plan was supposed to work, and why it didn't.

You can see Harrell setting a hard edge on the bottom of the play. He has the OT in the backfield and is able to come off to make a tackle attempt inside if the ball comes to him. He does get moved out a bit, which isn't ideal, but the play has to go inside of him.

Jenkins however does not have his blocker on the line of scrimmage. In order to stay in his gap he had to use most of his effort to get across from this blocker, with every foot he gives up vertically to do so a foot the running back can use. Same with the linebackers, except with them it's more about when they activate, how the contact point goes when the slam into their blocker's shoulder, how they get off that block, and how they do on the tackle. On this one Barrett did okay on the impact and disconnect parts, initiates his tackle at about 4 yards, and gets run over for another 2 yards as Jenkins comes off his block to finish.

This isn't tactical; this is the defense getting beat the normal way. Jenkins(-1) and Graham(-1) got moved to create some running space, Barrett got to his spot and made the tackle. The space between Jenkins and Graham in the image above is the space the running game has to operate in.

The above was optimal conditions: a defensive line that set up with a lot of space between the DTs, a linebacker that wasn't shooting his gap until he was certain the QB handed the ball off, no safeties coming down to help. The offense isn't blocking the backside end, so there's a blocker for every defensive hat. The defense is at a disadvantage against a base run here, chosen to give them an advantage against any throws.

We've seen Michigan's DTs win battles like these without needing Barrett's help. The thing about Stretch is it creates more of that space, albeit at the cost of movement downfield.

MOTION GAMES

So we know Michigan wants to play defense by setting a hard edge and winning with fewer players inside of that edge. We also established that Minnesota was able to use motion to stretch both edges of Michigan's defense. See where I'm going with this? The motion created more space between the edges, and Michigan's obsession with keeping second-level defenders strong against the pass took material out of the middle, meaning the guys responsible for the run were ending up with more horizontal space to defend with less help behind them.

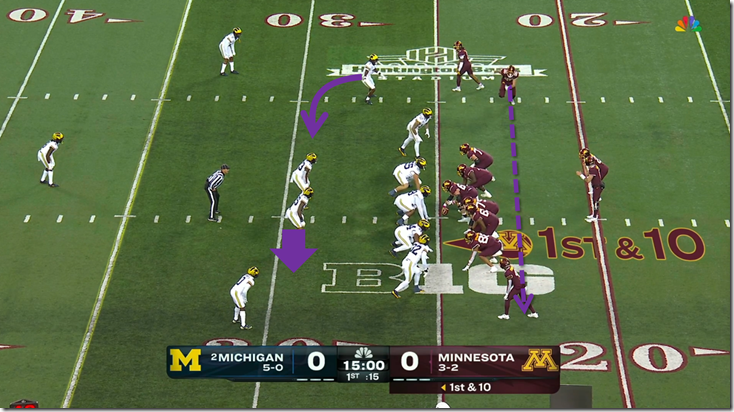

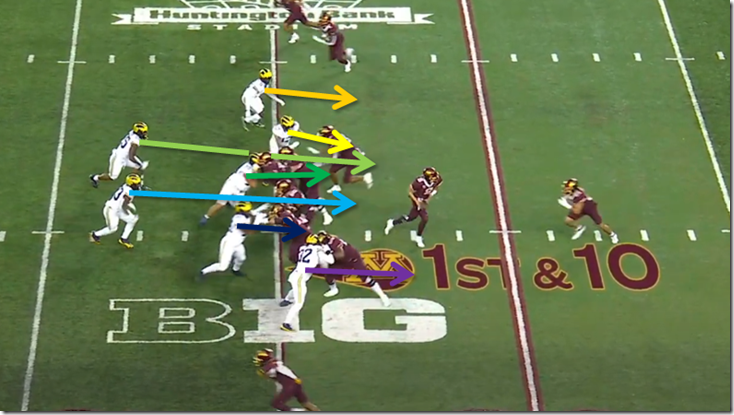

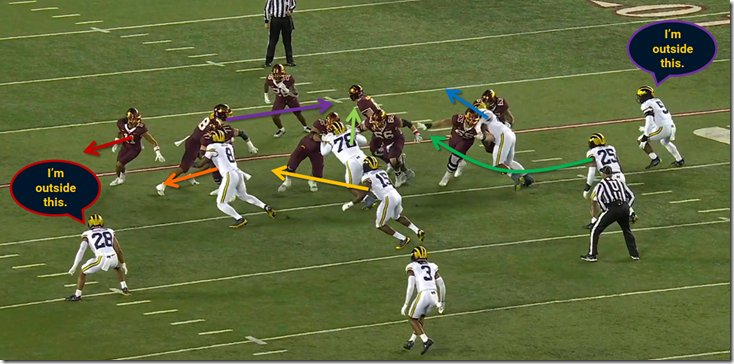

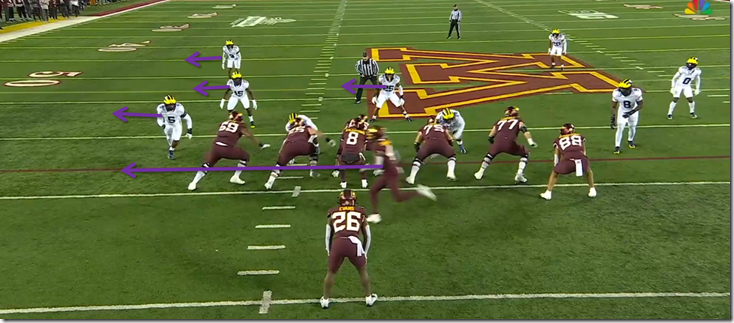

Here's Minnesota's second Stretch play:

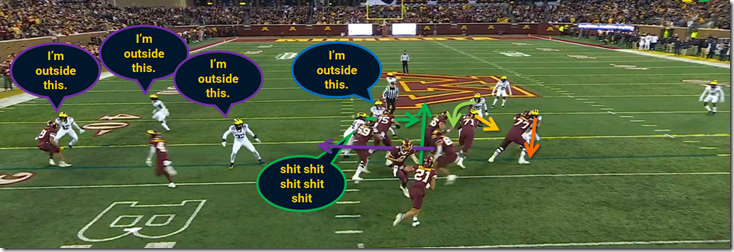

Look at all the backfield motion they're dealing with at the same time as the stretch blocking. Michigan's response seems to be having the DL slant to (our) right while the LBs replace the new backside gaps. But there's a problem with this plan:

Jenkins can't get across LG #75, and Barrett is hopping to the gap that Jenkins is actually in.

What I want you to notice is how much space this motion has added to the space Minnesota is attacking (everything between McGregor and Harrell). That's a much larger surface than the Bowling Green example. It's a much larger surface than the first stretch run that got six yards. This play has extra success because Jenkins lost his battle—he's not on the correct side of #75. Barrett has a chance to make him right by swapping gaps, but doesn't. In fact he's reacting to the TE still.

And since Colson isn't activating either the guy doubling Graham on the front side gets to choose if he wants to thunk him to make that gap wider or go hunting for the linebacker. He chooses Colson, and Graham is starting to fight back.

He gets a little bit held…

…and Jenkins can't squeeze the gap shut between them before the RB is through.

The live play really emphasizes how overcommitted Michigan is to defending the edge with all of the motion towards it, up to and including Harrell checking the quarterback. They've left all of that interior space to the tackles, with whatever assistance their linebackers might provide. Here they provide little assistance, and the DTs aren't superhuman for once.

An illegal motion that wasn't really relevant to the play got this one called back and Michigan covered a pass on 3rd down, but Minnesota went right back to the well on their next drive. Just like the play-action on the first play, a receiver motions across the formation pre-snap, and a tight end goes backside to feint a split zone block.

…and once again this looks like a VERY big surface for the DTs and their LB friends to cover between the edges.

This time the DTs are the backups and they're not given as tough of a job as the starters. Grant is supposed to occupy the frontside A gap and Benny is coming upfield after taking a shoulder from the guard while staying in the backside B gap. But as the tight end crosses them their gaps are changing. The DTs now need to get across the blockers in front of them so the LBs can take the gaps behind them.

Meanwhile the play is getting further away from him. The buck stops at Derrick Moore, but he's getting wide as the receiver pops out, since he can't let that guy take away the edge. The force player on the backside, Josiah Stewart, is also flat-footed. Is anything—run, pass, or bootleggy quarterback—getting outside those edges? No. But there's quite a lot of surface area for the defenders inside those edges to handle versus the same number of defensive players. Both DTs get to their gaps, though Benny let LG #65 release playside of himself (it's called getting scooped). That's okay as long as the backside guy doesn't do so as well, because by going vertical the OL is sacrificing his horizontal advantage.

Or it would be okay if the backside linebacker was able to make him right. Unfortunately Colson has picked up the TE coming across the formation and cheated so wide that he's almost off screen on our replay. When Benny gets across the LT there's nobody in the gap behind him until Stewart. The RB sees his lane is cut off at Grant, but works his eyes backside and sees a lane forming. He presses the gap to get Hausmann to commit to getting blocked by the center,

The hops behind Benny's back.

Luckily #65 got too far downfield and Colson is able to come upfield of him to join Quinten Johnson in shutting it down.

Their game established, Minnesota goes on a drive. Next play is the same play, with the announcers picking one guard to thank, either because they don't think you can figure out how multiple blocks and multiple guys can all matter to a play, or because it's hard to see what happened in one go and they're just making it up. I think you can figure it out now:

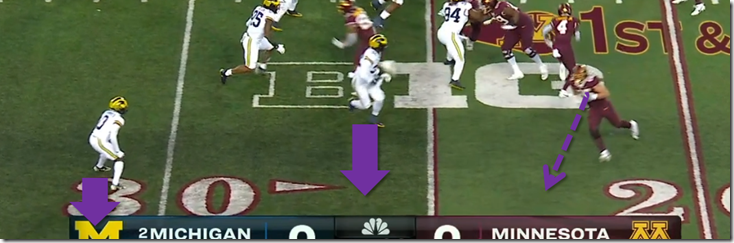

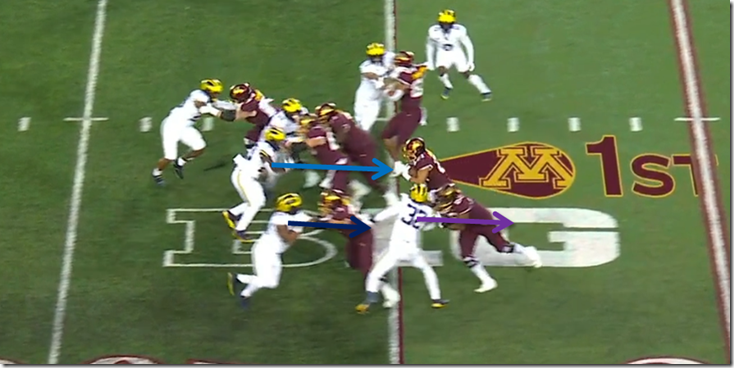

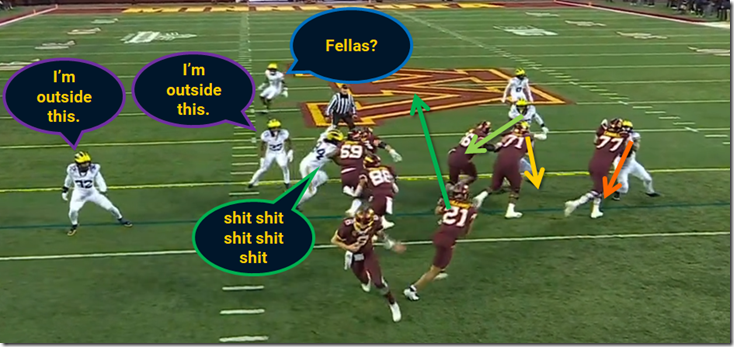

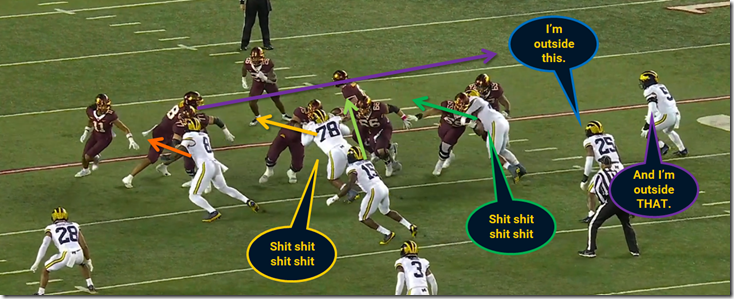

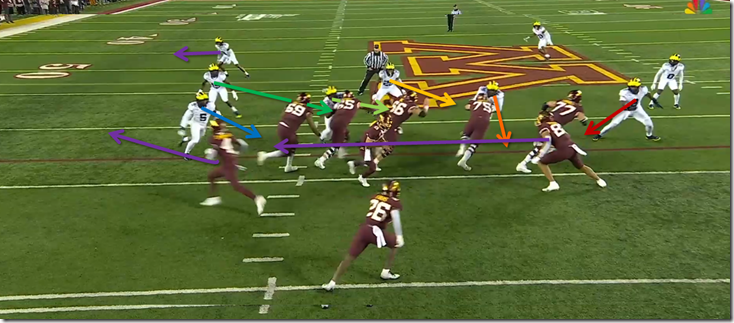

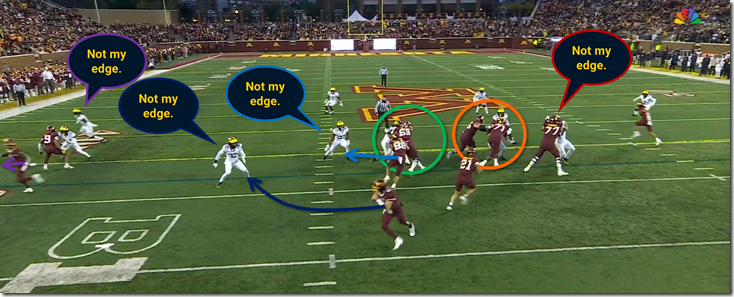

Pre-snap motion across from the wide receiver purple-shifts the front.

And post-snap motion across from the tight end double purple-shifts the front.

That stretches Colson's responsibilities too far, and he takes the coverage one. This time at least Michigan isn't leaving two guys back there, however. Stewart reacts to the crossing TE by crashing inside, which should in theory cut off the backside.

However the DTs haven't held up enough to pay it off. With Benny getting scooped by LG #65 and LT #69, and Grant getting super washed by RG #75 who's in his chest, and the linebackers shitting out backside, the center can lead through the gap.

Grant does deserve some blame because you want him to stop moving, but he was understandably racing to cross RG#75 to control his gap, and he's large, and reversing course when you're being ridden is hard. If you're requiring Grant and Benny to get across multiple blockers, then back across those blockers again, to cover all the space between where Moore set an edge on RT#77 and where Hausmann ended up, you're asking too much of your DTs.

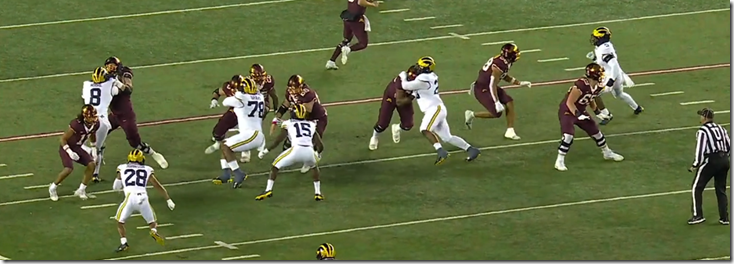

So of course next snap Minnesota ran it again. I'm not even labeling this one for you. Just watch the WR cross the formation to shift everyone's Grant and Hausmann behind him trying to get right while the TE steps out like he's going to crack Harrell, then turns inside and lead blocks as Harrell flies out of the play.

They probably could have kept on going because the next play was play-action off of this stuff and Michigan kills it because they're *still* overreacting to the pass, tackling this for a loss (that the refs marked out at the 41 because they were handing Minnesota extra yards like candy).

Notice something else though?

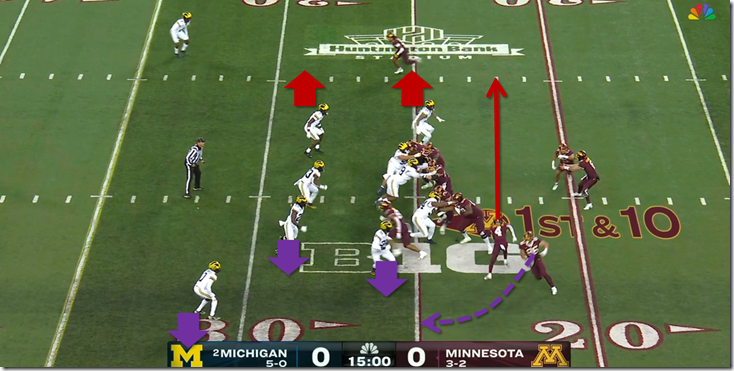

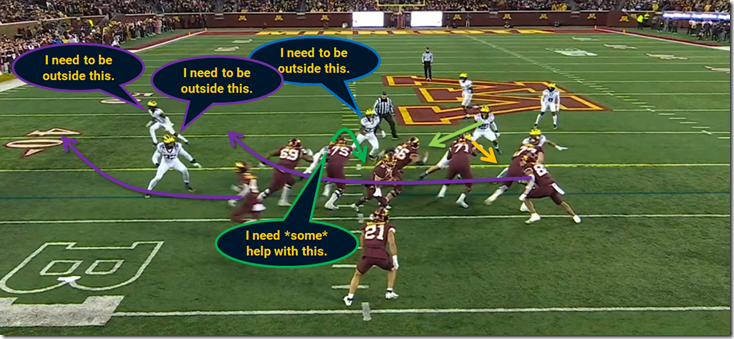

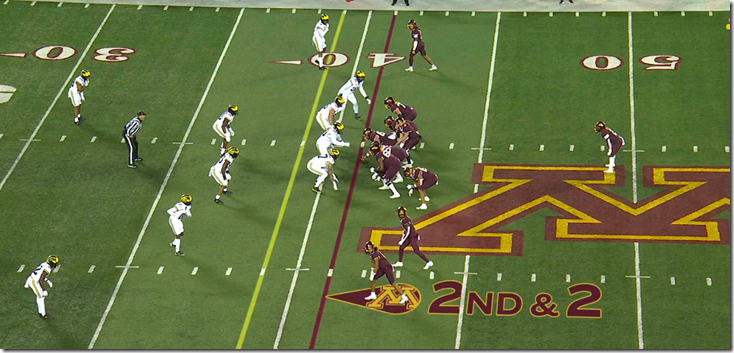

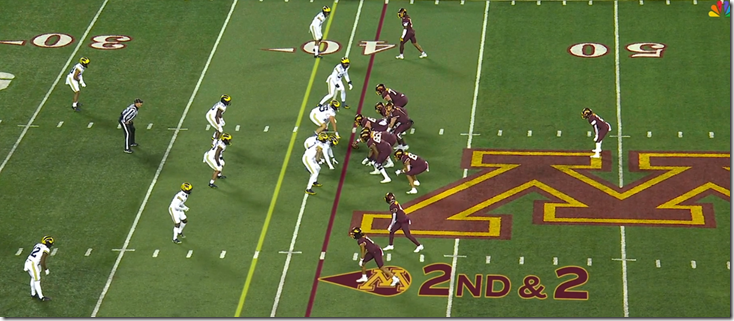

THE REACTION

Well after Minnesota converted on 3rd & short with a play-action pass that was insanely lucky not to be a sack or a bat-down, they went back to the well, and once again the Michigan DTs would have to do something outside human capacity to stop it.

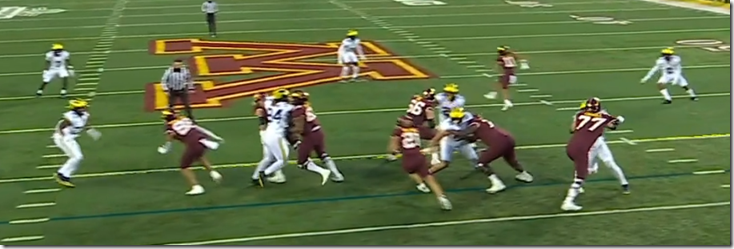

This was a reaction, although not one expected to go THIS well. Because Graham was so successful it actually hid how successful Michigan's reaction was going to be. For that we have to deconstruct a bit. Watch #23 Michael Barrett, the linebacker on the top, reacting to the WR crossing the formation. The gaps are still shifting when he goes by, but by bringing him down what was a weak node is now a powerful one. As for the TE crosser, since he gets stopped by Graham as well there is no widening on the backside. Michigan isn't actually expecting Graham to get upfield so fast that he tackles the RB on the handoff. They're expecting him to get upfield fast enough to intercept the crosser so that Jaylen Harrell can pinch the line down and the RB is forced to run into a hard node: Barrett or Jenkins. The surface area to defend has been both halved and compressed.

THE OTHER REACTION

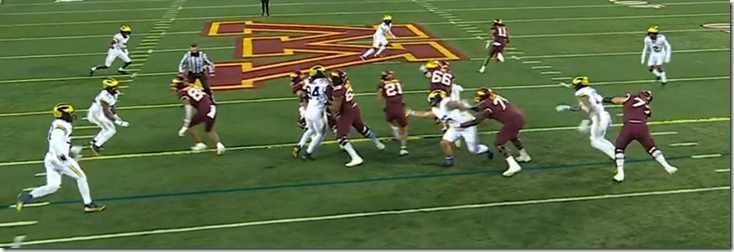

But for the times when Superhuman Mason Graham wasn't going to be available, I want to go back to the play-action I clipped one play ago. Watch the defensive line before the snap.

Specifically that the DL lined up in an under, waited for the offense to make their line calls, then shifted to an Over.

While they got play-action here, this would continue. Minnesota had a counter planned for that: they started setting up with multiple TEs or a TE and a WR on one side then if they got a shift they didn't like they'd flip them to the other side before starting the motions. Michigan varied their DL attacks enough that trying to stretch multiple gaps over was more likely than not to blow up in their faces. The next time they tried it the linemen slanted past their blockers, and the blockers had to try a new tactic.

Minnesota would get a few more good gains until putting this away in the second half, but with spotty reception, because all Michigan needed to do was shift correctly one time to put the Gophers behind the chains. There was one more I wanted to highlight however, because it seems they never did give up on making the DL fight across their blocks so they could save the linebackers for spill duty.

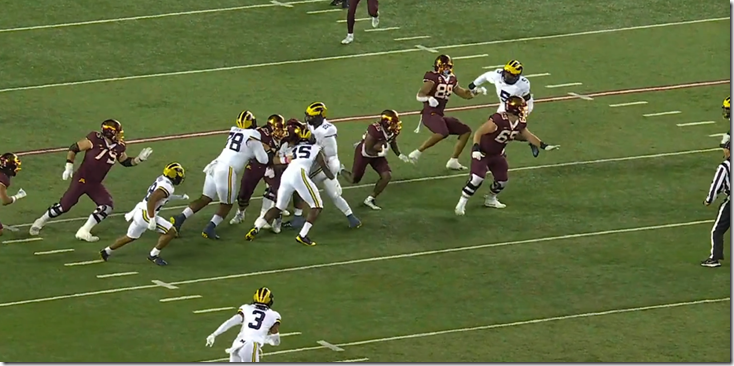

Or I should say "linebacker" because by making a five-man front they were only giving themselves one guy to clean up. Watch Michael Barrett, the lone LB. Minnesota is attacking the wide gap between the NT (Graham) and DE (McGregor) on the left, but the way they're doing that is to have McGregor get all the way from his Wide-7 alignment across the LT. It's a tough ask that he accomplishes, and the whole time Barrett is hanging out behind all of this, and ends up outside the TE in the end.

This is dangerous stuff they're playing with, but Michigan's certain their defensive linemen are good enough to handle this stuff on their own with just a few adjustments. We'll see if another line can cause as much damage as Minnesota's did. So far in UFR they're the first team to get a significant number of negatives on them.

As for whether Michigan is capable of actually defending these conventionally, yes. Here's what it looks like when their linebackers actually attack it instead of focusing on every motion and tight end who might go into coverage. I think the takeaway here isn't that Michigan struggles with zone stretch, although I think Benny and Grant could use some reps at it to prevent cutback lanes. It's that Michigan used the Minnesota game to practice the way they plan to play Ohio State. Yes they gave up some yards on the ground. But Kaliakmanis also had just 52 yards passing, minus 62 yards in pick-sixes.

October 10th, 2023 at 5:33 PM ^

Great stuff, Seth!

October 10th, 2023 at 6:21 PM ^

Well, Michigan is REALLY fucking on this season, that’s for sure! Whew. I remember the 2008-10 seasons very, very well (unfortunately).

October 10th, 2023 at 8:05 PM ^

This is some great stuff. Thank you!

October 10th, 2023 at 9:16 PM ^

You do such a great job explaining all of this, Seth. Thank you.

This might be a stupid question, but once that TE starts moving along the line of scrimmage, why not just have the weakside DE (Stewart?) just crash down to destroy him right away behind the line of scrimmage? It seems like it would solve three problems:

- it frees up the linebacker from having to worry about getting edged by the TE, so he can flow to the play without outside responsibilities.

- if Stewart can keep his helmet outside of the TE, he can still keep contain and prevent a cutback by the RB.

- You don't have to worry about the TE going on a route if it's a pass because he'll be stuffed by Stewart (again, behind the LoS, so no PI).

The same with this clip (below), where Colson was taken completely out of the play because he was worried about a TE that could've been eliminated by Stewart in the first place.

Probably another dumb question, but it looks like Michigan was running a 5-2 in that last clip you played. Would that have been better suited against what Minnesota was trying to do?

Anyway, thanks again for this.

October 11th, 2023 at 12:32 AM ^

They did start having the DE crash the TE. They also had Graham(!) crash the TE. But back to the DE, what they wanted to do was have a hat for a hat outside and let the DTs dominate doubles inside. There's one play I clipped (might have to draw it for UFR now) where there's a DE for the QB, a LB for the TE, and a S for the WR who all crossed to the outside before or after the snap. Then there were only two DTs and one LB left for four blockers and a RB. Kinda unfair.

The point is by having more guys down in the box Minnesota really required Michigan to match. They did and the leaks stopped for the most part.

October 11th, 2023 at 11:51 AM ^

Then there were only two DTs and one LB left for four blockers and a RB. Kinda unfair.

Yeah, I'd say that's a bit unfair.

Thanks for the response!

October 10th, 2023 at 9:22 PM ^

These are so great.

Thanks again!

October 10th, 2023 at 10:33 PM ^

A lot depends on what they are teaching the DL and LBs to do. A common way to handle reach block on the OZ is to try to fight through it to maintain your gap, but "if you get reach, stay reached" press from the back-side gap maintaining contact and shoving the blocker into the playside gap; the LB inside/back of you would see/feel that, and stack or scrape past you.

October 11th, 2023 at 9:16 AM ^

Takeaway, concerning thought, and questions:

Takeaway: Michigan repped addressing stretch-outside zone in the manner it expects to do from its base set against Ohio. Minnesota used its OL strength and some pre- and post-snap motion to mess with the LB reads in that set and gained some yards. Michigan ultimately countered by committing another player (or two) to the box-run, which shut down Minnesota.

Concerning thought: if Ohio did the same thing that Minnesota did, and required Michigan to respond by committing more resources to stopping the run rather than defending the pass ... then uh-oh, right? Because Marvin Harrison Jr., etc. etc.

Questions: can Ohio do the same thing that Minnesota did?

- Is Ohio's OL as stout as Minnesota's?

Judging from results-grading, one might think not--Ohio's running game has been fairly anemic this season. But is that inherent, or are teams like Maryland, ND, Ind., etc. committing players to stopping Ohio's run--i.e., are other teams already deploying the "counter" that Michigan deployed against Minn.?

- Does Minnesota's stretch "trick" require threats Ohio doesn't pose?

Using two motions, one pre-snap and one post-snap, to stress Michigan's edge defense requires two players that are a credible threat motioning across the backfield, right? Which means fewer players setting up outside, i.e., threatening more of the field. Thinking about that in the abstract--well, I guess I'd prefer if Ohio had MHJr & Co. motioning closer to the middle of the field where Michigan has more defenders. So .... in the end, that's not a trick Ohio wants to deploy, right?

College football chess. So preferable to think about than the horrors of the real world right now.

Comments