air raid

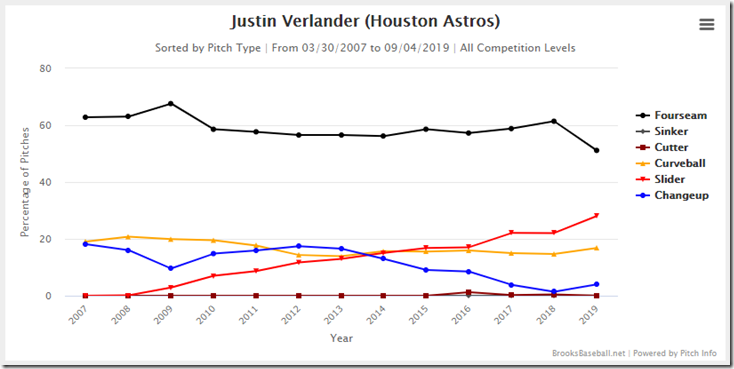

If you follow enough baseball you're familiar with the concept of a pitcher's second career. The story's always more complex but in broad strokes the kid who comes out dominating with a 101-mph fastball, and the things having a nuclear fastball lets you get away with, slowly builds up his repertoire as the heat begins to dissipate.

This doesn't even show it but Verlander's fastball rate dropped under 50% in 2020

Michigan's defense under Don Brown used to be that dominant fastball-changeup kid. As offenses adapted he was working in more offspeed stuff that play off the fastball, but didn't change the overall approach. That's not insane. If you're going to use your changeup as your primary pitch, you'd better be Luis Castillo. Or Iowa.

This year however they reached that inflection point. It's a dramatic one not only because Lavert Hill was replaced by a downgrade in Gemon Green, but their blazing heater Ambry Thomas opted out and the rest of the depth chart is so weak a shitty MSU rookie can knock them all over the yard. It looks so disorganized because everyone else is trying to make up for it. The DL is jumping the snap to add pressure. They're running more 3-3-5 and stunts for the same reason.

They're doubly unfortunate because downfield chucks are an underused play in the Big Ten. They're relatively low-risk, the ball gets out too quickly for your pass protection to matter, receivers have more game practice on them because they all caught a lot of fades in high school, and cornerbacks are disadvantaged even when they win the route because OPI is rarely called, and if they get run over by the receiver it's usually a flag. However lizard-brained coaches often think in terms of binary success rates, and eschew "low-percentage" plays with high upside. How many times have you heard a coach essentially apologizing for throwing downfield "just to keep them honest"? Show most coaches, especially underdogs, a flashing "Throw at Me!" sign, however, and they'll start doing the thing they should have been doing more of all along. We're making them more efficient than they want to be!

Mesh

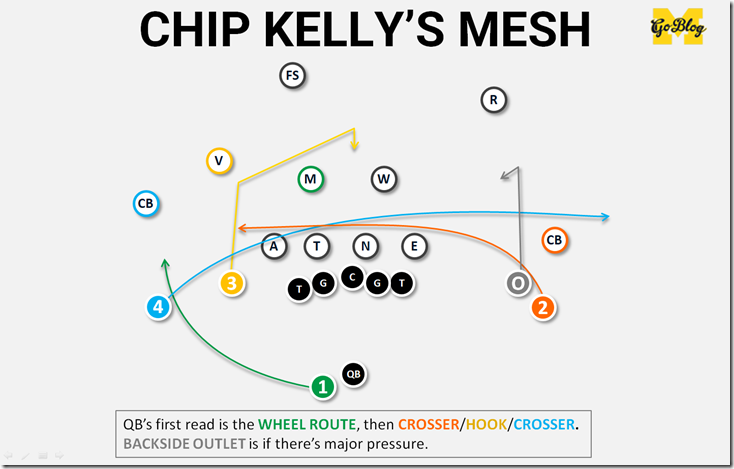

When talking in overall defensive structure there's too much to discuss, so let's pare it down to one play that's in almost every offense, and was a big part of Indiana's gameplan: MESH.

This is the Air Raid's base play. A lot of teams that run it, including Indiana and Ohio State, teach their crossers to high-five as they go by in order to get the right amount of spacing for the pick.

MESH is so loved because it's a play with a high upside and a high floor that isn't hard to teach and works against all defenses. It's been especially popular in the last decade as refs at all levels stopped calling the pick part offensive pass interference as long as the pick man tries to go on with his route. Also because teams have gotten used to running it with a leaky running back like above, which overloads defenses' ability to cover it.

If you catch man-to-man, the crossers create a natural pick route for one another, and give your crossers the leverage to take advantage of any speed differential between themselves and whoever's covering them. For this reason teams run MESH often against man defenses where they have a matchup disparity (e.g. Michigan used to match Zach Gentry against linebackers).

MESH also works against zone, because the crossers will be touring all of the linebacker zones, and can sit down in empty space between them. If you catch a blitz, you have two short reads to get the ball out in spaces that the blitz left open. If defenses start activating safeties against underneath routes you've primed them to get torched by deep ones.

It's also easy to teach your quarterback. You start by reading the MIKE (the playside ILB) to see if he's bailing for the RB. MIKE running outside means you probably have man-to-man, and one of the defenders potentially in between the crossing routes is no longer there. MIKE staying inside means the edge of the defense hasn't compensated for the extra player you sent there…yet. After this sweep from the middle to the edge, the QB knows all he needs to make his reads. If the mesh cleared out underneath, throw it to the RB. If it didn't, check the crosser emerging toward that edge. If that guy's covered, flick your eyes above him to see if the middle of the field was abandoned. And if the defense did shift everybody, you've got one-on-one coverage across all that traffic to the guy coming out the backside.

[After THE JUMP: Three ways to defend it]

I realize there was a drive and a half afterwards, but for all purposes this was the end of The Game:

In the aftermath there’s been some Michigan fans saying that this wasn’t something the coaches should have put on O’Korn to do—that it was too complicated for a guy who’s already not good at reacting to what’s in front of him.

I don’t think that’s accurate. Option routes in general are complicated because they put more on receivers, but for the quarterback it’s less complicated than a West Coast tree. He’s still seeing the coverage and making a read, it’s just that he gets to stare at the same receiver the whole time instead of finding each guy where he’s supposed to be. Now, the Run and Shoot, or its cousin the Air Raid: those are complicated for quarterbacks because he’s got to read multiple option routes. That’s not what Michigan was asking O’Korn to do on this play.

I’ll explain. Two bad things happened for Michigan to create this disaster:

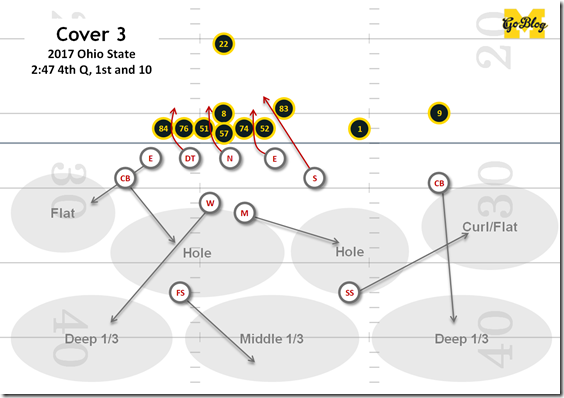

1. OHIO STATE DISGUISED THEIR COVERAGE

First, let’s go over what the announcing team said about it, since Gus Johnson and Joel Klatt did a good job of explaining what happened afterwards:

Ohio State switching coverage post-snap is half the story. They’re talking about the fact that Ohio State showed Cover 2 pre-snap and then ran a Cover 3 zone blitz, with the line slanting, the SAM blitzing, the weakside end dropping into the flat, and the WLB tasked with dropping into a deep 1/3rd zone.

[After THE JUMP what O’Korn saw]

"Every football team eventually arrives at a lead play: a "Number 1" play, a "bread and butter" play. It is the play that the team knows it must make go, and the one its opponents know they must stop. Continued success with it, of course, makes your Number 1 play, because from that success stems your own team's confidence." –Vince Lombardi

As we discuss coaching candidates we'll invariably get into the same old discussions on what kind of base offense said candidate might want to run. There was some discussion on the board this week and I wanted to expand that discussion into some basic "Rock" plays of various offensive schemes.

It is incorrect to identify any one play (and even more incorrect to identify a specific formation or personnel group) as a complete offense. You always need counters to keep doing the thing you do, and the counters will often borrow directly from some other offensive concept's rock. All offenses will borrow from each other so no breakdown is going to describe more than 60% of any given offense. Most zone blocking offenses throw in man-blocked things (example: inverted veer) to screw with the defense. You can run most of these out of lots of different formations. You can package counters into almost all of them (example: The Borges's Manbubble added a bubble screen to inside manball).

Really what you're describing when you talk about any offense is the thing they do so well that they can do it for 5 or 6 YPP all day long unless defenses do something unsound to stop it (like play man-to-man, or blitz guys out of coverage, etc.). Some examples of offenses and their formation needs (where a need isn't specified, figure they can use any set or formation: spread, tight, 23, ace whatever). I've given the rock plays, and left out the counters and counters to the counters because that gets into way too many variants.

Finally, the terms "pro style" and "spread" are meaningless distinctions. NFL offenses have the luxury of getting super complex: they have passing game coordinators who teach the QBs and WRs Air Raid things then run zone or power blocked things. The spread refers to formations and personnel—it doesn't say anything about whether the QB runs, if it's an option offense, or what tempo it runs at, or even what kind of blocking it uses. What I've done here is break up the offenses into "QB as Run Threat" and "QB Doesn't Have to Run" since the construction of these base plays usually stems from that. Remember, however, that QB running offenses can (and often do) still use blocking right out of Vince Lombardi's favorite play.

QB as Run Threat Offenses:

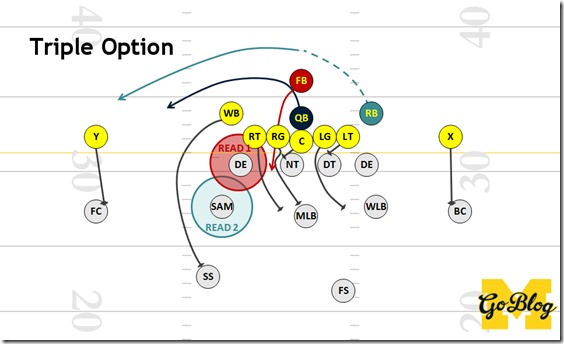

Triple Option

The FB dive will hit too quickly for anyone but the DE to stop; once the DE bites, the RG moves down to the second level while the QB keeps and heads outside, with the RB in a pitch relationship to defeat the unblocked defender there.

Concept: QB makes a hand-off read then a pitch read.

Makes life especially hard on: Edge defenders who have to string out plays against multiple blockers and maintain discipline.

Formation needs: Two backs.

Helpful skills: QB who can consistently make multiple reads and won't fumble, highly experienced, agile OL, backs who can both run and bock.

Mortal enemy: The Steel Curtain. Stopping the triple option is a team effort; if everybody is capable of defeating blocks, challenging ball-carriers, and swarming to the pitch man there's nowhere to attack.

Examples: Air Force, Nevada, Georgia Tech, Bo's Michigan

[Hit the jump for ZR, QB power, Air Raid, West Coast, Manball, Inside Zone, and the Power Sweep].

25