power off tackle

Purdue had an interesting approach to Michigan's running game. Rather than throw bodies at the problem like Illinois, or throw bodies at the problem and get their asses handed to them for the second year in a row except this time at home like Ohio State, Purdue decided to take a mixed approach: add an extra hitter, but try to disguise where he was going to be.

Here's the part you may have noticed: Often before the snap, the Purdue DTs were quickly shifting their fronts. One of the purposes of this was to try to draw a false start (they didn't). But there was more to it than that. The Boilers were trying to disguise their attacks so Michigan wouldn't be able to pick out oddities before the snap and adjust their schemes to take advantage of them. Let me show you.

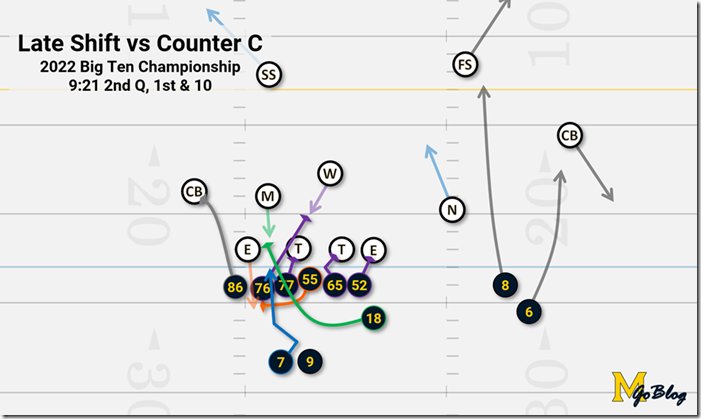

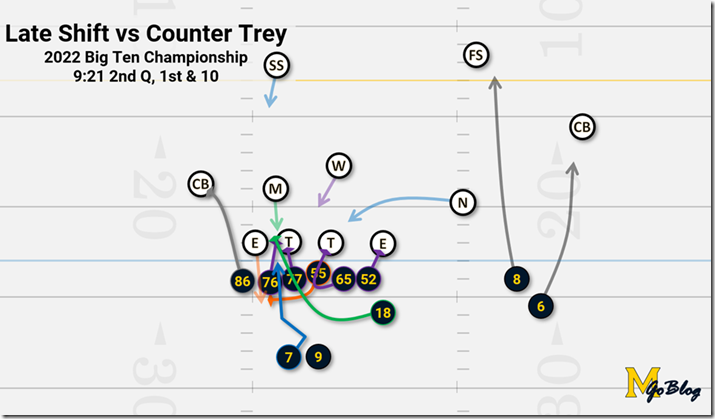

This is a run in the 2nd Quarter that got stuffed because Michigan set up for one blocking scheme and then didn't adjust on the fly when Purdue shifted the line late.

Power runs are brutal to observe on film so we'll go to my standardized color scheme:

- Purple: Blockdowns.

- Orange: Kickout.

- Green: Lead blocker.

- Blue: Running back, free hitter(s).

Here's what Michigan thinks they're getting before the shift.

Zooming in on the point of attack, Michigan wants to block down to the WLB, sealing both DTs with their guards, while kicking out the edge with their center and swinging Loveland around as a lead blocker. The hope with Counter is always that the defense will see your running back start moving to the opposite side and start shifting that way, creating a wider gap to run through.

Even before the snap however, Purdue does the opposite. Here's what Michigan really gets:

The only difference is the DTs moved over. Don't bother trying to parse out where everybody's going. Just look at the mess they've made of the point of attack. How're we supposed to run through that?

[After the JUMP: Another angle]

Nebraska fixed their atrocious linebackers by giving them aggressive reads. So Michigan unfixed them. [photo: Eric Upchurch]

I had a very hard time pulling anything interesting from this game. I wanted to see Michigan dominating with skill, speed, and play design, but the takeaway after a rewatch was Nebraska's linebackers were responsible for much of the Michigan offense's explosive day.

This was something of a surprise. In the film preview I thought the Huskers had found a good player in WLB Mohamed Barry (#7) and a serviceable one in MLB Dedrick Young (#5) by giving them easy Keys and telling them to play those aggressively. I think Michigan saw this too, and also a way to use that to make Nebraska's linebackers atrocious again.

So the play in question is the first snap of Michigan's second drive. They had already used it for a big Higdon run on the first drive but Nebraska did some funny stuff that time while this was straight-up pwnage.

Michigan is running two concepts on this play to screw with the Nebraska LBs' Keys. On the frontside it's Down G, and on the backside it's a Wham Block. Let's go over the bolded terms.

About Keys

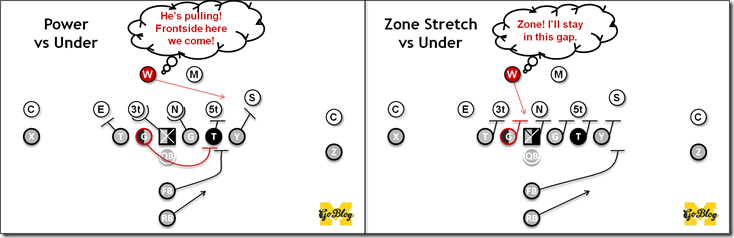

One of the great things about about Down G is how it messes with "Keys." Keys are cheats that defenses use to get extra defenders to the ball faster by identifying what the play is by certain types of backfield action. Every defense uses keys, and the game that running game coordinators are often playing is identifying what the defense's keys are then using that against them. The defense meanwhile will have different keys for different looks to punish an offense that just sticks to the plays they run well.

A highly common Key against power teams is to read your guard. The backside LB ("W" in the diagrams below) is often Keying the backside guard to decide what to do. If the guard pulls, that LB can guess the ball's going that way too and hightail it across the formation, arriving in the intended gap before the pulling guard and mucking everything up.

If that backside LB reads a zone block he doesn't activate so quickly, since he's got to cover that lane in case of a cutback. For completeness if the guard steps back to pass block, the LB knows to sink into coverage, or if the guard releases the LB knows to get playside and dodge the block.

Keying is a slider; you can use it as information while staying on your assignments, or tell your players to go hell for leather whenever they read one. Where you set that has to do with what your players are capable of doing on their own. If you have a particularly fast linebacker or one who can diagnose more things on his own, you don't have to try to cheat him into the right spot so much. Think back to 2011 Michigan with Brandin Hawthorne, who could knife through for some key stops or get caught paralyzed, versus Desmond Morgan, who though a true freshman was more diagnostic and decisive in his approach.

Nebraska is at the Hawthorne stage of a similarly wholesale rebuild. They're not as blitzball as the WMU and SMU linebackers when they Key run action, but they're up there with recent Rutgers and Minnesota teams Michigan's faced who don't wait to see the whites of their blockers' eyes before firing at a gap. As you may have derived from those memories, playing blitzball against a Harbaugh run game can get you a few stuffs followed by a good view of the back of Higdon's jersey. Except with the Huskers, it was a different shiny thing.

[After THE JUMP: Michigan's getting good at this, Nebraska was REALLY bad]

"Never mind the maneuvers, just go straight at them." –Horatio Nelson, maybe

This game was spectacularly unexciting from just about any standpoint, though my spot in the corner opposite the action and directly in the sunlight might be in the running for least spectacular fan experience.

On replay I thought most of Michigan's struggles running the ball were they were trying to practice running power into stacked boxes when the linebackers were firing aggressively at power and the safeties were starting at eight yards and stepping forward at the snap, not so different from what Michigan State does. So rather than show some amazing adjustment to the very unsound thing SMU was doing, I thought it might be interesting to pick apart one Power run where Michigan needed to get two yards and failed to do so.

1. The Primary Gap

The setup: It's 3rd and 2 later in the 1st quarter, about the point where Michigan needs to make it 7-0 to prevent what was supposed to be a laugher from turning into a grumbler. Michigan comes out their Heavy (fullback + two tight ends) formation, with both tight ends on the front side.

What happened? Michigan ran power, SMU slanted into it, Evans tried to cut back, and there were two unblocked guys waiting for him there.

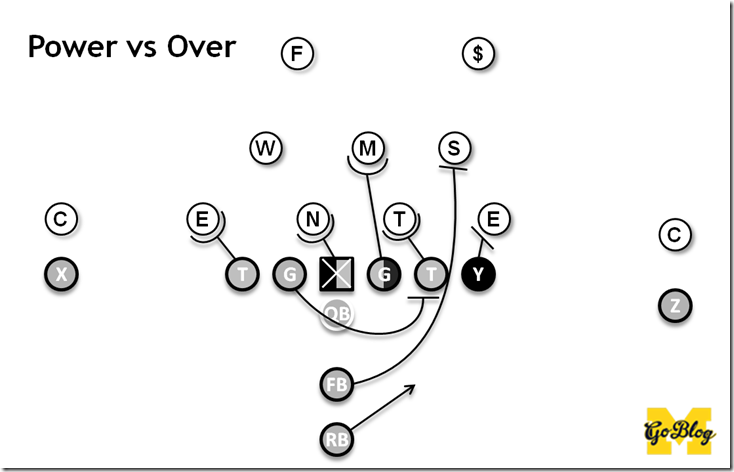

What's Power? Power, or Power-O (for off-tackle) is God's play. It's a gap play where you try to pry open the frontside of the defense and then send all a bunch of material into it before the defense can close it down.

You block down on the linemen to the backside of the play, kick out the edge, and—this is the key—pull a blocker from the backside of the formation to thwack whoever appears in the gap. Send any unused frontside blockers into the linebacker level, add fullbackery and other frippery as necessary, and serve. Mostly that's changing up who gets the kickout block versus the playside linebacker (e.g. have the fullback kick and the tight end release on that SLB).

Power is one of the few plays that deserves a spot in the pantheon of base plays that can work against virtually any defense if you're good at it. My main takeaway from this game is Michigan wants to learn power until the offense can punch its way out of a coffin with it, and the coaches' opinion of SMU's defense was they might make a solid practice plank:

[After the JUMP: Michigan breaks its hand]

What if the two most important blocks of an inside run game were easy?

14